Dianne Feinstein and the problem of America's aging politicians

How do you nudge out an incapacitated lawmaker?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) has returned to work after nearly three months spent recuperating in San Francisco from a bad case of shingles. A week after her May 10 return, spokesman Adam Russell confirmed a New York Times report that Feinstein's shingles infection was more severe than previously acknowledged.

Feinstein, 89, had encephalitis, or a swelling of the brain, and Ramsay Hunt syndrome, a type of facial paralysis, Russell said in a statement. Post-shingles encephalitis can "leave patients with lasting memory or language problems, sleep disorders, bouts of confusion, mood disorders, headaches and difficulties walking," the Times reported, adding that Feinstein appears "shockingly diminished" and "disoriented."

Feinstein insists she will not resign, but the "bleak reality," the paper said, is that she wasn't ready to return to work, and she is "struggling to function in a job that demands long days, near-constant engagement on an array of crucial policy issues and high-stakes decision-making."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

There is no age cap for holding office or required cognitive ability, and America's leaders aren't young: President Biden is 80, former President Donald Trump is 76, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) is 82 and recently spent weeks away from work after injuring himself in a fall, and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) is only relatively young at 72. The median age in the Senate is 65.3 and in the House, 57.9. In the U.S., it's about 38.

Rep. Katie Porter (D-Calif.), who is running to replace Feinstein, told CNN that "we need some forward-looking policies. ... What are you going to do when someone becomes infirm, either for the short term or the long term?"

Time for a forced-exit strategy

Feinstein's memory problems "are an open secret on Capitol Hill," and she should have resigned ages ago, Jim Geraghty wrote at National Review. Not that 80-year-old Biden can tell her to step down, but Republicans "have their own share of geriatric senators," including Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa), who is also 89. "The country would be better off if there were clearer 'rules of the road' for when a lawmaker should retire, or when age becomes an impediment to a lawmaker's ability to do his job."

Former South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley (R), 51, proposed one solution when she launched her presidential campaign in February, saying that if she's elected, "the permanent politician will finally retire," and the U.S. will "have term limits for Congress and mandatory mental competency tests for politicians over 75 years old." The U.S. "is not past our prime," she added. "It's just that our politicians are past theirs."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The Senate has a "long history of members who missed months, even years, of votes, and returned frail and sometimes confused," and America survived, David Lightman wrote in The Sacramento Bee. A frail Sen. Carter Glass (D-Va.), 87, returned to the Senate in 1945 after a two-year absence, and Sen. Clair Engle (D-Calif.) "had a brain tumor and was partially paralyzed when the roll was called on breaking a filibuster on the Civil Rights Act of 1964. He was able to lift his arm and point to his eye, and was recorded as an 'aye' vote. He died six weeks later." Even Biden was absent for seven months of 1988, "recovering from operations to repair brain aneurysms."

There are reasons other than infirmity to put older politicians out to pasture, Aksel Sundström and Daniel Stockemer wrote at The Conversation. "The under-representation of young adults in decision-making can mean that issues important to them fall off the agenda — climate change being the most obvious. And their relative absence can contribute to a vicious cycle of alienation" and political apathy.

Ageism is worse than gerontocracy

Washington has become a gerontocracy, but "there are huge individual differences in how people age," Oregon State University gerontologist Carolyn Aldwin told Slate. "Some are sharp as a tack at 90 or 100, some have cognitive impairment in their 50s." Also, "if you're gonna start down that road of saying people are unfit for office because of a personal issue, why limit it to age?" added David Reuben at the UCLA Center of Health Sciences. Alcoholics, gamblers, and sex addicts can also make poor decisions.

Age limits are "disrespectful, if not quite disenfranchisement, of older voters," Spelman College political scientist Dorian Brown Crosby told Politico Magazine. The only real solution is for lawmakers themselves to "take an internal assessment" of their capacity to serve.

An incapacitated president can be removed with the 25th Amendment, but in Congress, the only remedy is expulsion — a tool that requires a two-thirds majority and was last employed in the collegial Senate in 1862, said University of Texas law professor Steve Vladeck. Senators could force Feinstein from office, for example, but "there is little chance they would pull that lever," Brent D. Griffiths wrote at Insider. "Expelling a senator for being too infirm to perform their duties would set a precedent that could easily befall one of her colleagues in the future."

If nothing else, Feinstein's health issues have "prompted awkward public ruminations among lawmakers about their own mortality," Politico reported. "It's a very hard situation," said Sen. Jon Tester (D-Mont.). "Let's face it, when I'm 89 years old I'll be long dead. Trust me."

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Ballot drop boxes set on fire in Oregon, Washington

Ballot drop boxes set on fire in Oregon, WashingtonSpeed Read Hundreds of submitted ballots were destroyed in Vancouver, Washington

-

Newsom chooses Laphonza Butler to fill Dianne Feinstein's Senate seat

Newsom chooses Laphonza Butler to fill Dianne Feinstein's Senate seatSpeed Read California's governor kept his promise to appoint a Black woman to the Senate, but Butler was an unexpected choice

-

Sen. Dianne Feinstein returns to D.C. after extended absence, Democratic tensions

Sen. Dianne Feinstein returns to D.C. after extended absence, Democratic tensionsSpeed Read

-

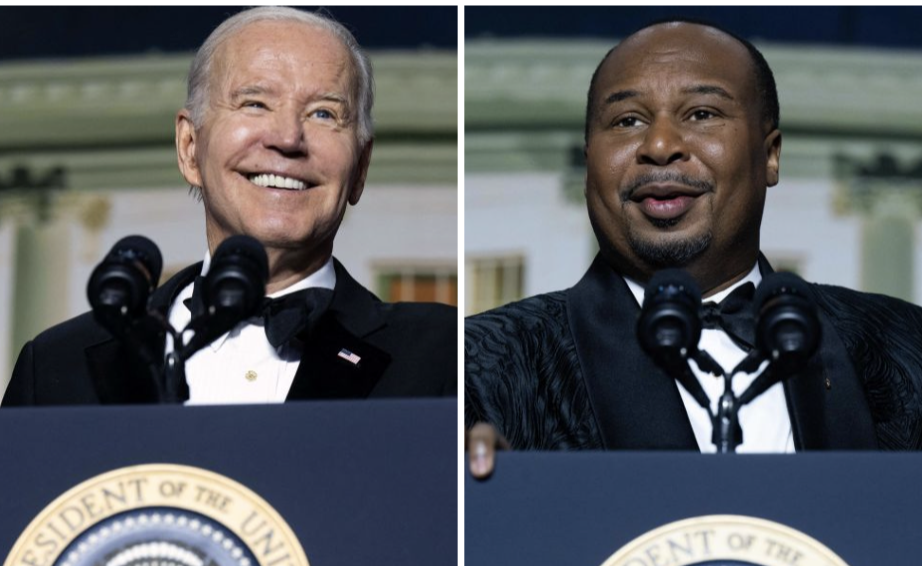

Biden, Roy Wood Jr. serve up laughs at White House Correspondents' Dinner

Biden, Roy Wood Jr. serve up laughs at White House Correspondents' DinnerSpeed Read

-

Senate GOP blocks Democrats from temporarily replacing Sen. Dianne Feinstein on Judiciary Committee

Senate GOP blocks Democrats from temporarily replacing Sen. Dianne Feinstein on Judiciary CommitteeSpeed Read

-

Secret Service responds after White House fence is breached by toddler

Secret Service responds after White House fence is breached by toddlerSpeed Read

-

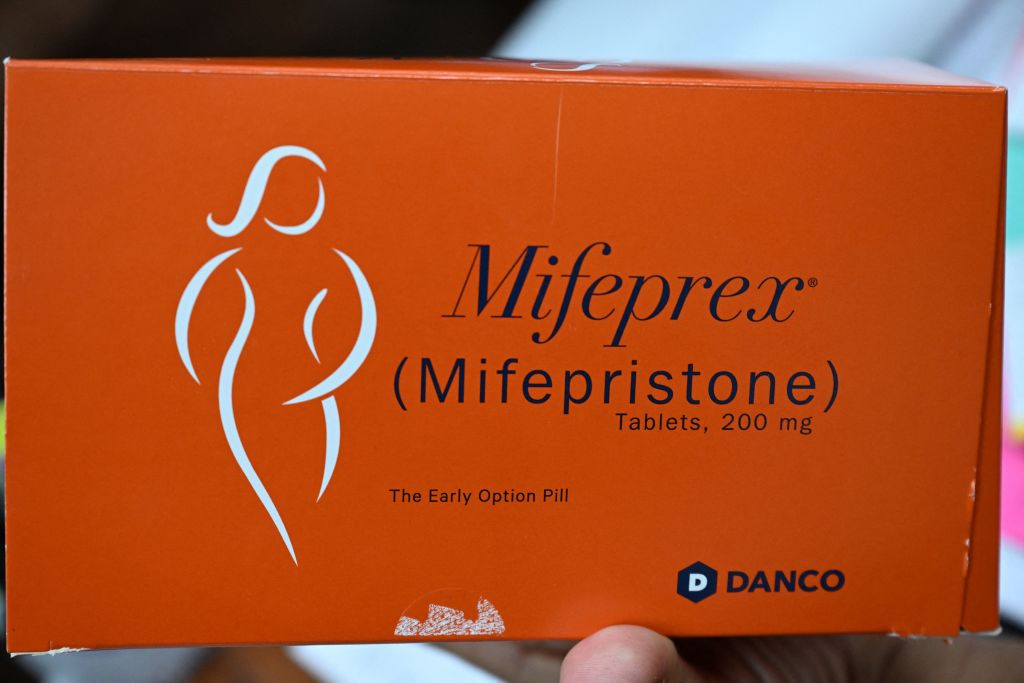

Competing federal rulings spell trouble for abortion pill access

Competing federal rulings spell trouble for abortion pill accessSpeed Read

-

Sen. Dianne Feinstein announces retirement at the end of her term

Sen. Dianne Feinstein announces retirement at the end of her termSpeed Read