Why journalist deaths continue to rise around the world

Journalist deaths rose sharply in 2022 and don't appear to be slowing down this year

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

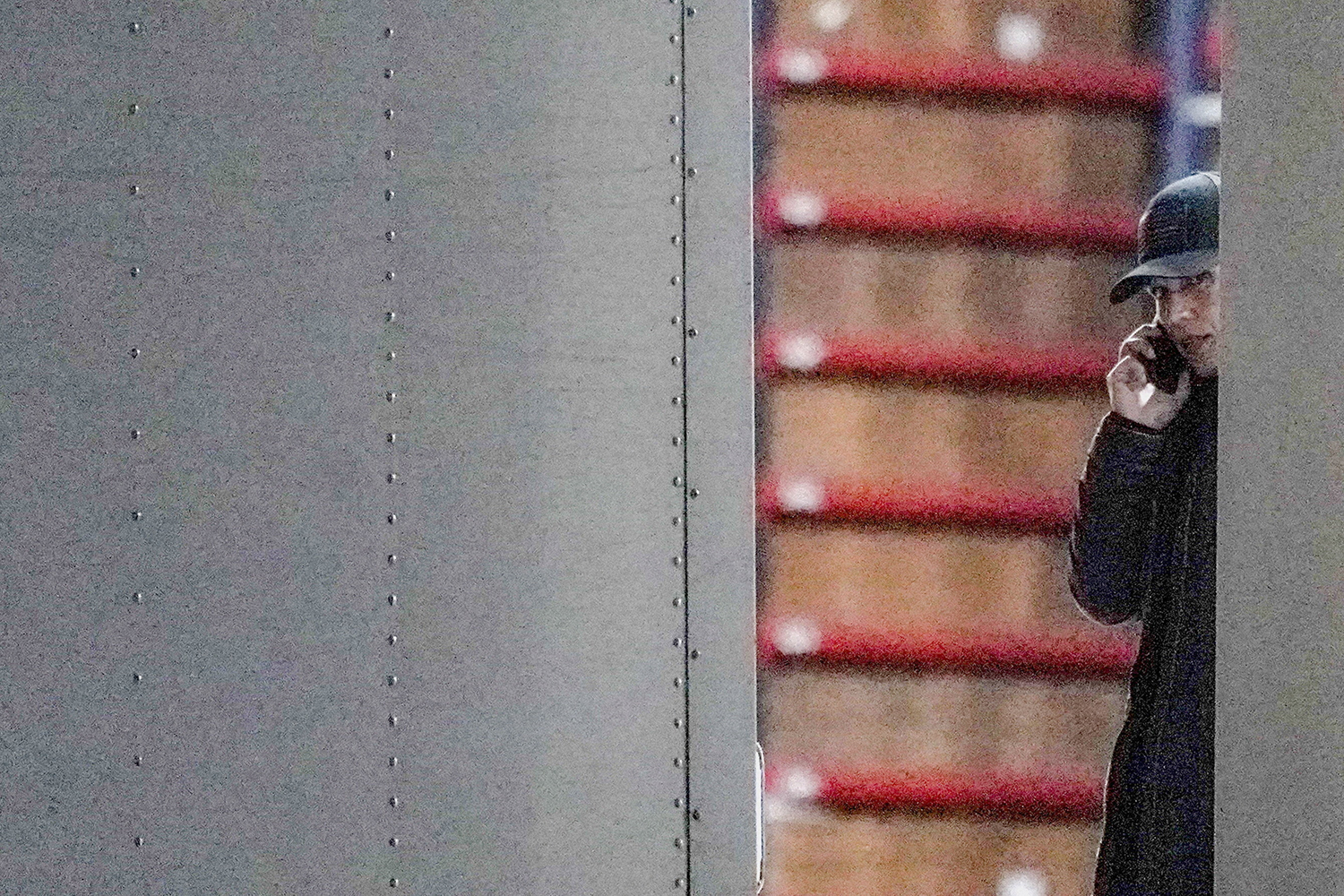

Mexico is reeling from a pair of shocking journalist deaths. The director of a local news site in Acapulco, Nelson Matus, was shot to death in his car in what was reportedly the third assassination attempt against him. Matus' death came just one week after the body of Luis Martin Sanchez, a reporter for Mexican national newspaper La Jornada, was discovered near the city of Tepic.

But Mexico is hardly alone in the epidemic of violence against journalists. Across the world, 67 journalists, writers, and reporters were killed in 2022, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ). This represents the "highest number [of journalist deaths] since 2018 and an almost 50% increase from 2021," CPJ reported. And that violence has only continued in 2023, as CPJ has tracked 14 journalists who have been killed so far this year.

Violence against journalists isn't new, as front-line reporting has always been a risky profession. Even in the United States, "violent acts against the media are as old as our nation," The Conversation reported. But what has led to the continued spate of violent, and often deadly, assaults against journalists in recent years?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Where are journalists mostly being killed?

Many journalist deaths in 2022 were due to the breakout of war in Ukraine, and this has continued in 2023. Producer Bohdan Bitik and AFP video journalist Arman Soldin were killed during Ukrainian-Russian crossfire, with Bitik "shot and killed on April 26" and Soldin "killed in a rocket attack on May 9," according to CPJ. This is a continuation of the staggering 15 reporters killed in Ukraine last year, and "journalists covering the war in Ukraine 'face enormous risk,'" CPJ said, per The Associated Press.

Half of the journalist deaths in 2022 occurred in just three countries, CPJ reported: Ukraine, Mexico and Haiti. However, this year has seen a larger rise in journalist deaths on one specific continent: Africa. Much of this violence is concentrated in the west-central African nation of Cameroon, which is "one of the most oppressive countries on the continent," The Guardian reported. Two reporters, broadcaster Martinez Zogo and radio presenter Jean-Jacques Ola Bebe, were killed this year, CPJ reported. A common motto for reporters in Cameroon has become "you can kill a journalist but you cannot kill the story," per The Guardian. But this is not the only African country where violence is being seen, as CPJ has also reported journalist deaths in Rwanda and Lesotho.

Latin America and the Caribbean have also been a hotbed of journalistic violence, with CPJ reporting 30 deaths in this region in 2022 — more than in Ukraine. Deaths in these countries have continued this year, with CPJ reporting journalists killed in Colombia and Paraguay, along with the two deaths in Mexico.

What has led to this rise in violence?

While the violence in Ukraine is an obvious factor, a rise in "global political instability" is leading to violence against journalists who are not in war zones, CPJ President Jodie Ginsburg told PBS. Ginsburg noted that the high level of deaths in Latin America has come even though the region is "officially not in any conflict."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In Mexico, for example, "we see journalists killed for covering corruption, particularly in local politics," Ginsburg said, noting that "local journalists are incredibly vulnerable. They often don't have the protections afforded to them by working for a big national media outlet." In Haiti, where journalists are often targeted, there has "effectively [been] a complete collapse of any authority," Ginsburg said. "People are covering gang warfare, but it's all part of a bigger pattern of increased lawlessness in the region."

The most dangerous time to be a journalist is "often not when an autocratic government is in full control," journalist Katherine Corcoran told The New York Times, "but when democracy begins to take hold and the power centers shift."

Even the dichotomy of covering conflicts has changed, "as even war reporters were once protected by the symbiotic relationship they had with those they covered," The New Republic reported in 2018. Combatants had to talk to journalists to communicate with the outside world, so "killing journalists, quite simply, undermined their ability to get their message out." However, "that dynamic changed with the advent of the internet," allowing for the continued carnage against journalists to go largely unchecked.

Justin Klawans has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022. He began his career covering local news before joining Newsweek as a breaking news reporter, where he wrote about politics, national and global affairs, business, crime, sports, film, television and other news. Justin has also freelanced for outlets including Collider and United Press International.

-

Democrats push for ICE accountability

Democrats push for ICE accountabilityFeature U.S. citizens shot and violently detained by immigration agents testify at Capitol Hill hearing

-

The price of sporting glory

The price of sporting gloryFeature The Milan-Cortina Winter Olympics kicked off this week. Will Italy regret playing host?

-

Fulton County: A dress rehearsal for election theft?

Fulton County: A dress rehearsal for election theft?Feature Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard is Trump's de facto ‘voter fraud’ czar

-

Experts discover why dogs wag their tails

Experts discover why dogs wag their tailsTall Tales And other stories from the stranger side of life

-

Luton Airport bendy buses join Ukraine war effort

Luton Airport bendy buses join Ukraine war effortfeature And other stories from the stranger side of life

-

Would North Korean weapons tilt the war Russia’s way?

Would North Korean weapons tilt the war Russia’s way?Today's Big Question Putin wants to boost ‘depleted stocks’ but Pyongyang’s arms may be in poor condition

-

Can the Ukraine-Russia Black Sea grain deal be rescued?

Can the Ukraine-Russia Black Sea grain deal be rescued?Today's Big Question The Kremlin’s termination of agreement has sparked fears among food-insecure countries

-

Zelenskyy sacks Ukraine ambassador to UK after sarcasm row

Zelenskyy sacks Ukraine ambassador to UK after sarcasm rowSpeed Read Vadym Prystaiko accused his boss of an ‘unhealthy sarcasm’ in response to British defence secretary Ben Wallace

-

Non-aligned no longer: Sweden embraces Nato

Non-aligned no longer: Sweden embraces Natofeature While Swedes believe it will make them safer Turkey’s grip over the alliance worries some

-

Should Ukraine be admitted to NATO?

Should Ukraine be admitted to NATO?Talking Point With this week's Vilnius summit, Ukraine's possible accession to the military alliance is more than a little top of mind

-

Mexican mayor marries a crocodile

Mexican mayor marries a crocodilefeature And other stories from the stranger side of life