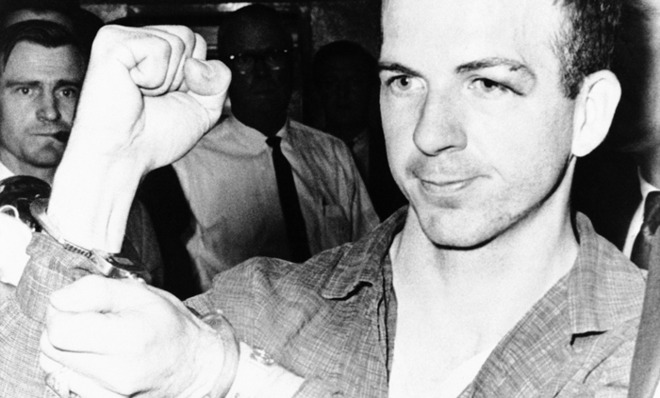

How I figured out that Lee Harvey Oswald killed JFK

My journey to unbelief

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Confession: I am a JFK assassination buff. I never much liked the term, but it describes me well. I've read just about every book ever published on the assassination, watched every documentary, mock trial, and dramatization. And for a long time, until about 14 years ago, I was a conspiracy theory believer. Too many loose ends. Too many coincidences of propinquity. And since I had no understanding of physics, or ballistics, or medicine, or of the world, really, I was fascinated with Oliver Stone's enormously influential JFK. I remember writing somewhere, and bear in mind I was 14 at the time, that the third act scene with "Mr. X" was one of the most dramatic moments in modern film history. That might have been true to a kid who hadn't seen many movies and who had no idea how awful New Orleans prosecutor Jim Garrison actually was, or how utterly absurd his theories were.

A year later, the day that Gerald Posner's Case Closed came out, I remember sitting in my high school library waiting for my chance to page through U.S. News and World Report, which was serializing the chapter on the "single bullet." I was nervous. Part of me didn't want to read a book that concluded something that was precisely the opposite of what I believed. But, clearly, I wasn't totally convinced, because I wanted to read it in the first place.

I took the magazine and began to read. I can pinpoint the moment when my blinders came off, when my childhood assassination conspiracy fantasies dissolved. Posner pointed out that (a) the president's row of seats inside the presidential limousine were built to be higher than the row of seats where Gov. John Connally and his wife, Nellie, would sit; and (b) all the photographs of the motorcade entering Dealey Plaza showed Connally sitting closer to Nellie, away from the edge of the car.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

And suddenly, the single bullet theory made absolute sense. The trajectory of a bullet fired from the Texas School Book Depository absolutely could have entered JFK's upper back, exited his throat, and tumbled through the governor, lodging, finally, in his leg. The two men were perfectly aligned. It was just true. No "in mid-air, mind you, the bullet changed direction." None of that was necessary. If the single bullet theory had to be true — and it did, because no one was capable of firing two bullets at precisely the same "x," one of them hitting Kennedy and the other missing Kennedy and hitting Connally on an angle that passed through JFK's torso — then everything else I thought I knew had to be questioned.

Keep in mind: I was 15. This was a seminal intellectual experience for me. It was my first exposure to the powers of skepticism and reasoned argument.

Reason triumphed over magical thinking. If Lee Harvey Oswald was part of a conspiracy, then Ruth Paine, a friend of his family's in Dallas, had to be, too, because she alerted Oswald to the open job at the Texas School Book Depository about a month and a half before the assassination. Come to think of it, Roy Truly, the building superintendent, also had to be part of the conspiracy, because he hired Oswald and assigned him to the fifth and sixth floors of the building. In other words, if Oswald was long-slated to be the patsy, unless a conspiracy fomented somehow REALLY fast in the last six weeks before Kennedy's death, those two HAD to be in on it. Had to be. But clearly, they weren't. Not only was their no evidence of their connection to anyone bad, save Oswald, but no one ever tried to silence them. Their stories checked out. And they were paragons of the community. They just weren't part of the conspiracy because there was no conspiracy.

What about... what about enigmatic David Ferrie, who was mob boss Carlos Marcello's pilot, and who also knew Lee Harvey Oswald from childhood? Well, turns out that Ferrie was never Marcello's pilot — he was a contract employee at one point, but that's about it, and there's no evidence he ever knew Oswald.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What about the famous horrific snapping back of the president's head right after a bullet tore through his skull? Actually, his head gets pushed forward, violently, before it snaps back, both of which are entirely consistent with a shot entering the occiput and existing above the right ear, blowing out brain tissue.

None of it hung together. The evidence of Oswald's guilt was, and is, overwhelming. The evidence for a conspiracy is thin to non-existent, and is almost always predicated on assumptions that themselves are very sketchy.

I do understand the sociological significance of the conspiracy theories. JFK's death was incredibly traumatic; how could a figure of such enormous historical importance be felled by a puny, angry, disturbed ex-Marine? But he was. That's kind of amazing.

Marc Ambinder is TheWeek.com's editor-at-large. He is the author, with D.B. Grady, of The Command and Deep State: Inside the Government Secrecy Industry. Marc is also a contributing editor for The Atlantic and GQ. Formerly, he served as White House correspondent for National Journal, chief political consultant for CBS News, and politics editor at The Atlantic. Marc is a 2001 graduate of Harvard. He is married to Michael Park, a corporate strategy consultant, and lives in Los Angeles.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

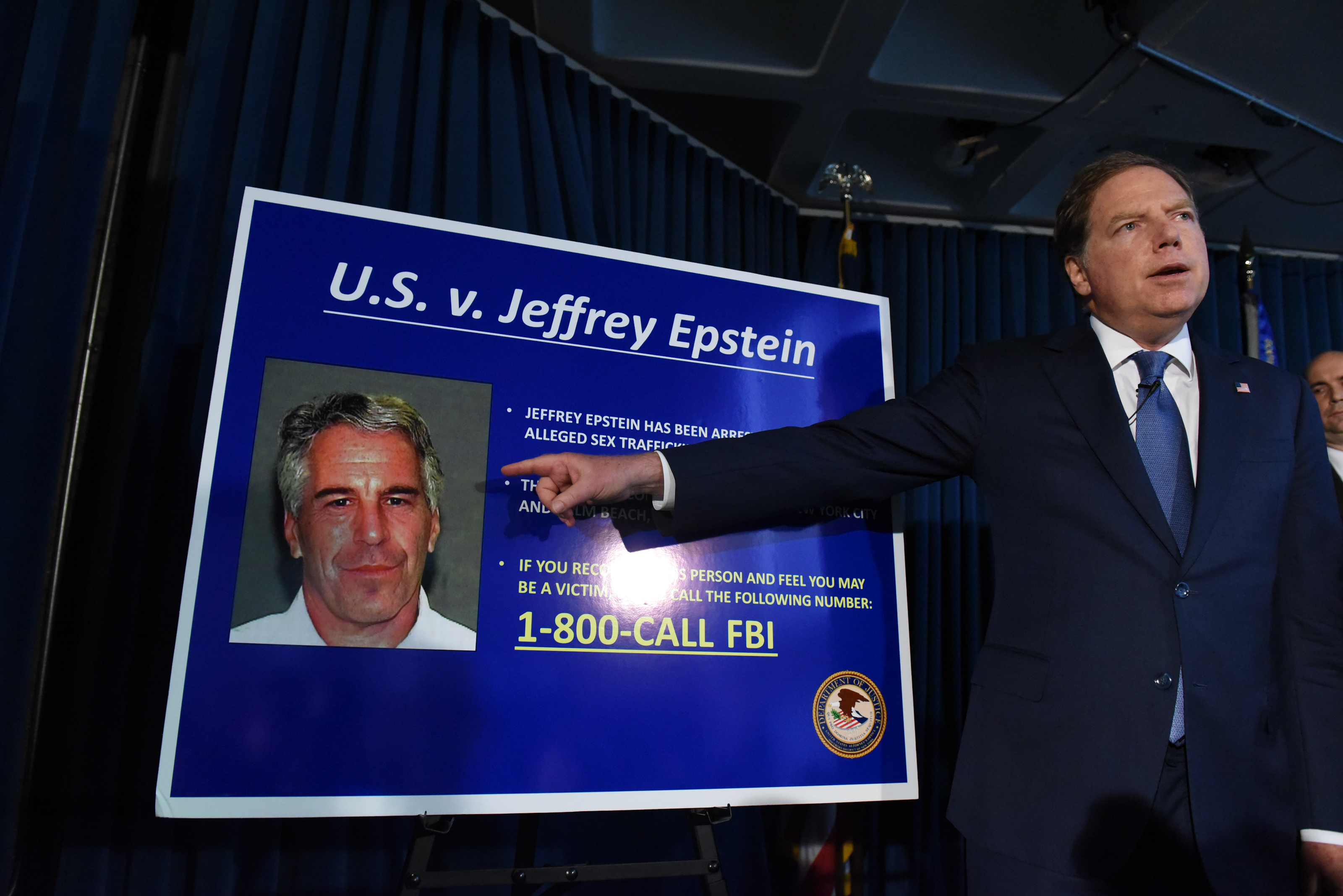

7 lingering questions about Jeffrey Epstein's death

7 lingering questions about Jeffrey Epstein's deathThe Explainer Truth can be as strange as conspiracy theories

-

3 things everyone is getting wrong about the El Paso-Dayton shootings

3 things everyone is getting wrong about the El Paso-Dayton shootingsThe Explainer Mental illness is a red herring — but so is Trump

-

Is it dangerous to lionize the heroes of school shootings?

Is it dangerous to lionize the heroes of school shootings?The Explainer Honoring the children who die saving classmates is laudable — but we should tread carefully

-

The fear we all live with

The fear we all live withThe Explainer What mass shootings have done to the American psyche

-

The sick phenomenon of school shooting contagion

The sick phenomenon of school shooting contagionThe Explainer Mass shootings can spread like a disease, with each massacre inspiring new rampages. Can the cycle of violence be stopped?

-

Why the Parkland conspiracy theories are different

Why the Parkland conspiracy theories are differentThe Explainer They aren't an attempt to make crazy sense of a senseless tragedy. They are a way of saying to the tragedy's victims and survivors: You aren't even worth arguing with.

-

Sex, drugs, and the Summer of Love

Sex, drugs, and the Summer of LoveThe Explainer Fifty years ago this summer, 75,000 young people flocked to San Francisco to "turn on, tune in, drop out"

-

What we know about gun violence may surprise you

What we know about gun violence may surprise youThe Explainer Contradictions abound