America is complicit in ISIS's rise. But that doesn't mean we should bomb Iraq.

America has long tried to "help" Iraq with military intervention. It's not working.

The extremist-fueled sectarian conflicts in Iraq and Syria are, by all accounts, unspeakably awful. ISIS has reportedly crucified people, buried women and children alive, decimated historic Christian communities, and even beheaded children.

And so here in the States, the clamor for President Obama to do something seems to grow louder by the day. That's largely why President Obama unveiled a potentially multiyear plan of airstrikes in a nationally televised address on Wednesday. Even those who tend to oppose military intervention, like Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.) and conservative New York Times columnist Ross Douthat, have argued that fighting ISIS is somehow different — that the president must take decisive action — that this, finally, is "the right war."

In many less-hawkish circles, much of the desire to do something is motivated by the role U.S. foreign policy played in creating a climate in which ISIS can thrive. As Paul argued, "Our recent foreign policy has allowed radical jihadists to proliferate." He's right. The last decade of meandering, ill-justified war in Iraq in particular has made America complicit in ISIS's rise. There would be no ISIS had America not invaded Iraq in 2003.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

And while I appreciate Paul's provision of a more measured response than has been supplied by the likes of Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.), I can't follow him in his call for more war. Dropping bombs and trillions of dollars into a situation we clearly don't understand and can't control hasn't worked yet, and it's naïve to believe it will start working now. In the words of the Decider of the 2003 invasion, "Fool me once, shame on — shame on you. Fool me — can't get fooled again."

Likewise, the refrain that ISIS, like past Middle Eastern monsters, is an existential threat to American security fails to convince. As Bruce Fein has ably demonstrated, it is laughable to suggest that ISIS could successfully make war on American territory — and it is equally ridiculous to listen to those very fearmongers who claim otherwise as they attempt to make further war inevitable.

Yet I, too, can't shake the feeling of responsibility. Now, I never supported war in Iraq in any sense more meaningful than a 15-year-old's ingenuous assumption that the president wouldn't screw up so important an issue. Today, I (and a majority of Americans) deem the Iraq War a failure. But the long-term impact of American intervention can't be negated by ignoring it or wishing it away.

So what can America to do help? And by help, I mean actually help, in a very literal sense of the word, not deploying drones for democracy or some such nonsense. What if, instead of sending bombs and weapons, we sent only relief aid: food, medicine, and evacuation opportunities? Indeed, continued humanitarian aid is a part of Obama's strategy. But it should be the only part.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

I make this suggestion as an anti-war libertarian who is as opposed to getting re-entangled in Iraq and making relief aid the government's domain as any libertarian can be. But I also recognize that the last decade of disastrous American foreign policy lays at our feet some responsibility to help those subject to ISIS's brutality; and a purely humanitarian response could potentially fulfill that obligation without launching Iraq War 3.0.

There are a number of advantages to this proposal. First, emergency relief aid does not engender the kind of resentment and retribution that airstrikes and military occupation produce. Second, there's no risk of humanitarian aid's being turned against us in the future. Weapons and equipment can fall into the wrong hands — and indeed they already have in Iraq and Syria — accidentally arming current or future enemies. Food and medicine will, in the worst-case scenario, feed and heal jihadists. Not ideal, certainly, but not adding to the American or Iraqi body count, either.

Finally, as much as Americans may want the president to act against ISIS, our appetite for war is hardly voracious. Though support for interventionism is trending up, it's been less than a year since desire for the U.S. to mind its own business internationally hit a 50-year high. Even now, just 31 percent of Americans think the U.S. does too little to solve the world's problems. With relief aid, the demand for action could be sated without the exhaustion of another war.

As Daniel Larison succinctly put it at The American Conservative this June, "The question is not whether the U.S. has done a great deal to create the current situation in Iraq — obviously it has — but what the U.S. can constructively do to remedy the country's many woes." Larison is correct when he says it is likely impossible to fully mete out justice, and that the American record of "helping" Iraq has to date been abysmal.

Ultimately, there is no good reason to believe that waging more war will magically turn out different this time. Granted, there is likewise no good reason to believe that relief aid will, equally magically, "fix" the damage American foreign policy has done. But it does offer a real alternative to repetition of a decade of mistakes, and better that we offer an imperfect remedy of peace than an already-failed panacea of violence.

Bonnie Kristian was a deputy editor and acting editor-in-chief of TheWeek.com. She is a columnist at Christianity Today and author of Untrustworthy: The Knowledge Crisis Breaking Our Brains, Polluting Our Politics, and Corrupting Christian Community (forthcoming 2022) and A Flexible Faith: Rethinking What It Means to Follow Jesus Today (2018). Her writing has also appeared at Time Magazine, CNN, USA Today, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times, and The American Conservative, among other outlets.

-

Interest rate cut: the winners and losers

Interest rate cut: the winners and losersThe Explainer The Bank of England's rate cut is not good news for everyone

-

Quiz of The Week: 3 – 9 May

Quiz of The Week: 3 – 9 MayHave you been paying attention to The Week's news?

-

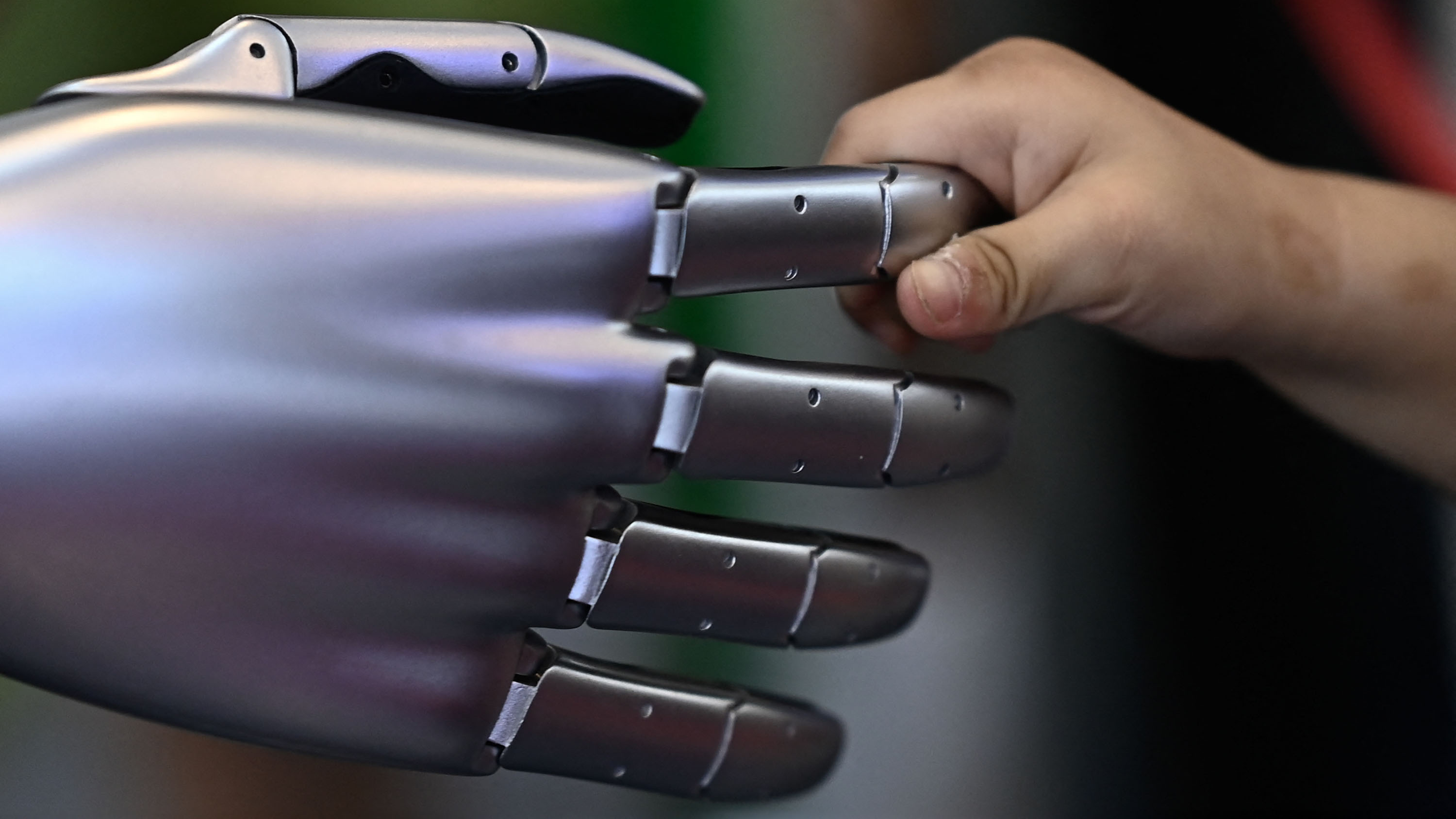

The Week Unwrapped: Will robots benefit from a sense of touch?

The Week Unwrapped: Will robots benefit from a sense of touch?Podcast Plus, has Donald Trump given centrism a new lease of life? And was it wrong to release the deadly film Rust?