Why America shouldn't panic over Putin

Russia's strong-willed leader is back for a third term as president. And as long as Mitt Romney cools the "number one geopolitical foe" talk, we'll be just fine

Contrary to what many Americans expect, Vladimir Putin's return to the Russian presidency need not cause a deterioration of relations between the United States and Russia. Many assume that Putin benefits politically from indulging anti-Americanism, and that in his new presidential term, he'll pursue increasingly adversarial policies. This underestimates Putin's willingness to strike pragmatic deals with Western governments. Putin has had a longstanding interest in cooperating with America — so long as Russian interests are respected and acknowledged. It would be foolish to ignore this in the mistaken belief that the two countries are ideological or geopolitical foes.

To understand why U.S.-Russian relations do not have to suffer from another Putin presidency, we have to remember why they were so poor during his last tenure. Putin believes that the Bush administration repaid his supportive gestures in the early 2000s with provocations. Following the 9/11 attacks, Russia was the first to offer support to the Bush administration, and Moscow accepted a U.S. military presence in Central Asia in a significant reversal of Russia's position. In return, Russia received nothing. Instead, the U.S. withdrew from the ABM Treaty, continued to expand NATO into the Baltics, supported anti-Russian "color" revolutions in ex-Soviet republics, proposed NATO membership for Ukraine and Georgia, planned missile defense installations in eastern Europe, and recognized Kosovo independence. That all formed a pattern of hostile acts that Putin viewed with increasing alarm.

Putin will likely be in office for the next decade, and the U.S. should find a way to work with him.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

This accounts for most of Putin's rhetoric and actions in recent years. As Angus Roxburgh, author of The Strongman: Putin and the Struggle for Russia, recently explained, "Putin's foreign policy has always been reactive. He responds to positive gestures with goodwill, and to pressure by pulling down the shutters or even lashing out." Contrary to the idea that the Russian government is unpredictable, its responses to perceived Western provocations are not only predictable but easily foreseen. The best way to keep U.S.-Russian relations from returning to their 2008 nadir is to give Putin good reason to believe that future cooperation on his part will not be met with new affronts.

So far, improved U.S.-Russian relations have been based on a series of transactional exchanges that have benefited both parties. The original agenda of the Obama administration's so-called "reset" policy has mostly been completed. All that remains for the U.S. to benefit fully is to repeal the archaic Jackson-Vanik amendment, which remains in place more than 20 years after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. The amendment blocks the establishment of permanent normal trade relations with Russia, which effectively bars U.S. companies from taking advantage of Russian membership in the World Trade Organization. Delaying that repeal, or tying it to the passage of other legislation to "replace" it, will simply deprive U.S. businesses of opportunities that will surely be seized by international competitors.

No matter what, the U.S. and Russia will continue to be at odds over the usual points of contention, including missile defense in Europe. This issue will always be an irritant as long as the U.S. insists on developing and deploying this technology, but it is something that can be managed. As a result, both governments should be able to have these disagreements in the context of a more normal, stable, bilateral relationship. Since it is also more likely than not that Putin will be in office for the next decade, the U.S. has an incentive to find a way to work with him to secure common interests. Putin's new term represents another opportunity to cultivate good relations with Russia under his leadership — an opportunity that the previous administration squandered.

Unfortunately, a stable and improving relationship with Russia seems to hinge on the outcome of our own presidential election. The U.S.-Russian relationship is more likely to decline if Mitt Romney wins in November. Romney has made a point of telling the American public and the Russians that he intends to undo most of the gains of the last three years. As Romney likes to say, he will reset the "reset," which effectively means taking the relationship back to its lowest point since the end of the Cold War. He also claims that Russia is "our number one geopolitical foe," and Russians will surely assume that he is going to govern accordingly. Nothing seems more likely to provoke the worst from Putin's "reactive" foreign policy.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Daniel Larison has a Ph.D. in history and is a contributing editor at The American Conservative. He also writes on the blog Eunomia.

-

Fed holds rates steady, bucking Trump pressure

Fed holds rates steady, bucking Trump pressureSpeed Read The Federal Reserve voted to keep its benchmark interest rate unchanged

-

Judge slams ICE violations amid growing backlash

Judge slams ICE violations amid growing backlashSpeed Read ‘ICE is not a law unto itself,’ said a federal judge after the agency violated at least 96 court orders

-

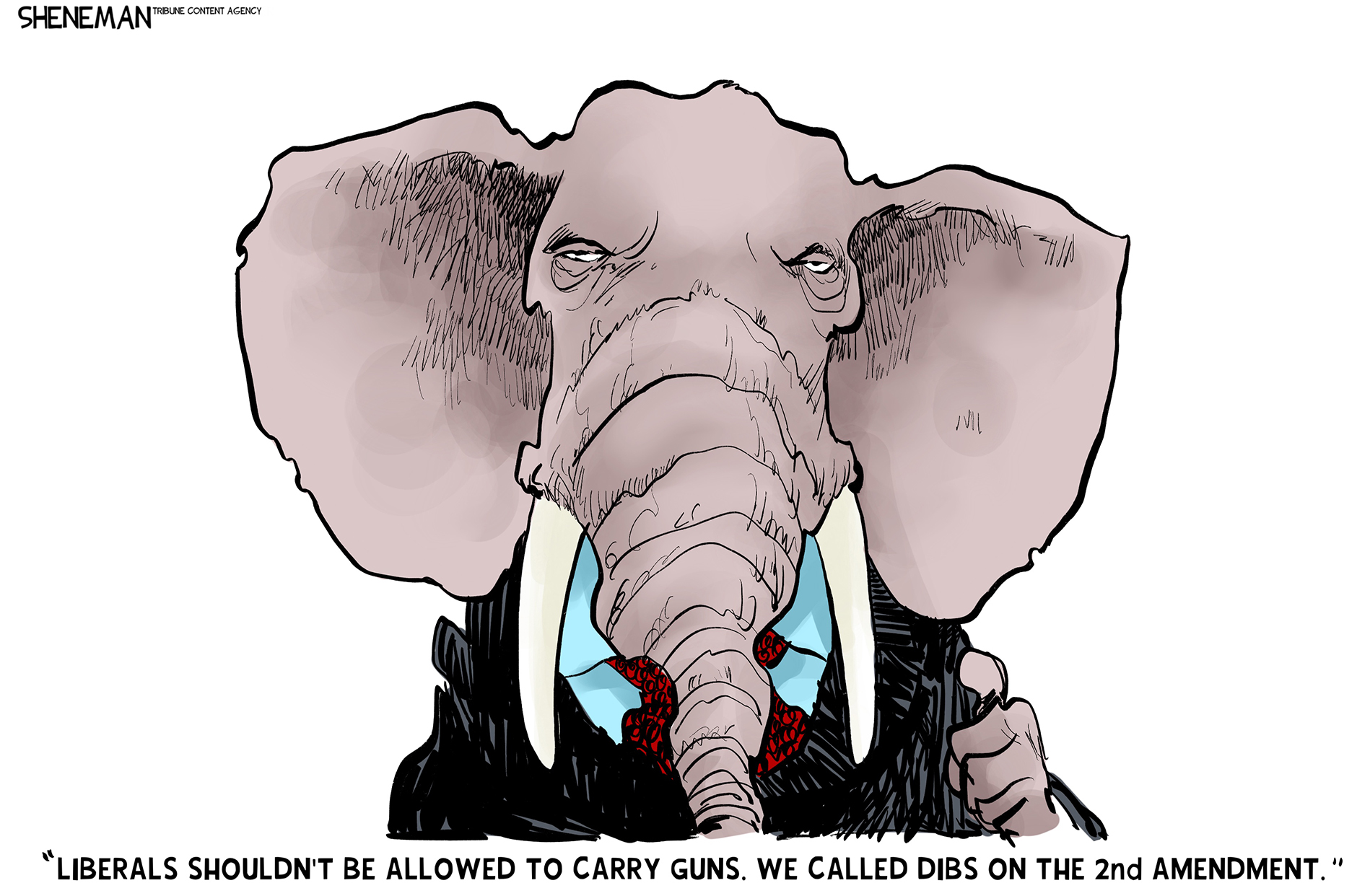

Political cartoons for January 29

Political cartoons for January 29Cartoons Thursday's political cartoons include 2nd amendment dibs, disturbing news, and AI-inflated bills

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred