Is this Clinton's third term?

When Barack Obama vowed to 'turn the page' in his historic 2008 campaign, I didn't think he meant turning a page in the old Clinton playbook.

What was it Barack Obama said at the 2007 Iowa Jefferson-Jackson Day Dinner? What was it that fired up his campaign, opening the path to victory in Iowa and to the Inaugural platform just a year ago this week?

He pledged to lead "not by polls but by principle; not by calculation but by conviction." Without ever mentioning her name or her husband’s, Obama took a devastating shot at Hillary Clinton’s cautious campaign, which implicitly offered restoration, not change. Obama, the candidate who that night proclaimed "the fierce urgency of now," indicted the last Democratic administration for its timidity; he invoked Bill Clinton’s indelibly trademarked phrase and thrashed it, saying, "Triangulating and poll-driven positions just won’t do."

But in the wake of a mismanaged and misread special election, the president suddenly seems headed—and is certainly being pushed— toward a third Clinton term. Politico’s John Harris and Carol Lee foresee a turn toward a "tepid and defensive-minded progressivism." On that count, at least, it was Hillary who was the real deal in the 2008 primaries.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In a post-Massachusetts interview, Obama sounded an uncharacteristic call to retreat.He could settle for a scaled down health bill, he said. "I would advise"—aren’t presidents supposed to lead?—"that we try to ... coalesce around core elements" of reform. Which ones did he single out? Insurance reforms, help for small business, and cost-containment, the Holy Grail for White House bean counters who converted the moral cause of health care for all into an accounting exercise.

Apparently left out of Obama's "core" are tens of millions who would remain without coverage—out in the cold, or in the ER when they get too sick to struggle on. What was it that Obama vowed in his Jefferson-Jackson Day appeal? To "make sure every single American has health care they can count on ... [not] 20 years from now ... [or] 10 years from now, but by the end of my first term."

That won’t happen by the end of a third Clinton term.

I believed—and still hope—that Obama’s better than that, and that he remembers what he campaigned for and why he was elected. But the hints, the leaks, his own tentative language, and the eruption of Democratic panic all point toward a bite-sized agenda, including a minimalist health bill. Perhaps most telling in that morning-after interview with George Stephanopoulos was that the president sounded far more comfortable talking about "credit card reform" than health reform.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Ironically, painfully, this reaction comes on the verge of victory for universal health care, and in response to the loss of the Senate seat held by Ted Kennedy, who called it "the cause of my life." There are Republican strategists who privately concede that a passel of competent Democratic candidates could have, would have, won the special election. Given the closeness of the margin, even Coakley might have won if she hadn’t polluted the closing days by describing Curt Schilling as a "Yankees fan," opining that Catholics shouldn’t work in emergency rooms, and dissing the notion of standing in the cold shaking hands at Fenway Park. (She explained that she had used her time to meet with—and this is beyond belief—politicians.)

Yes, Massachusetts voters were confused and worried about health care. But Coakley never bothered to explain that the health bill was good for Massachusetts, which already has near-universal coverage, because it would provide offsetting relief on Medicaid costs—the state wouldn’t be penalized for being ahead of the country.

Polls hadn’t even closed before this worst hurrah of a campaign was being recast as a last hurrah for health reform and progressive politics. The White House reluctantly, the Blue Dogs happily, and even a phalanx of congressional liberals swiftly yielded to this line.

Neurotic Democrats too often flee an adverse wind. Based on his steadiness in the 2008 campaign, I thought Obama was different— more like Ronald Reagan, who believed enough in his project to stay the course despite a midterm shellacking, the sudden unpopularity of Reaganomics and a presidential approval rating that bottomed out at 35 percent. Reagan became a transformative president precisely because he refused to waver, then rode an economic upturn to personal victory and ideological vindication.

Obama’s ratings are nowhere near 35 percent and he shares a key asset with Reagan: he’s liked by the vast majority of Americans. Obama, too, can stay the course. But the danger here is that this president, prodded by his failed, Clinton-steeped chief of staff, Rahm Emanuel, will prove unwilling to dare greatly for great purposes.

If Democrats don’t pass health reform, they will carry all the downside of having proposed it—the fictions of death panels, rationing, and out-of-control spending—without the political benefits of a law that, once in place, would become too popular to repeal. George W. Bush, not my usual exemplar, understood this when he pushed through a Medicare prescription drug benefit that was supported by only 19 percent of people over 55—and opposed by a plurality of Americans who, in effect, said go back to the drawing board. Sound familiar? Today, no one with political sense would suggest rolling back that law.

The Democratic retreat in sight would not be entirely Obama’s responsibility. Too many House Democrats, out of pride or ideological purity, have signaled that they won’t agree to pass the Senate version of the bill, which would allow the president to sign it into law. (It could then be revised in the budget reconciliation process.)

I don’t know if the president and Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi can persuade House Democrats to look beyond their frustration and bruised egos. But it would be better than turning tail, denying health coverage to more than 30 million Americans and leaving those who do have it to the untender mercies of the insurance industry. This is the only route to anything but a wan and incremental bill—and another prolonged, unpopular debate during which the GOP will again exploit Obama’s unrequited reach for bipartisanship, pounding every proposal and every Democrat who votes for it.

The Senate is not a serious option. It may not even be a serious legislative body. Leave aside Scott Brown, the Republican victor in Massachusetts who swore to be the 41st vote to "kill the bill." Leave aside, too, the reflexive, nihilistic Republican bloc. More than ever, the quaking Evan Bayh and his ilk and the duplicitous Joe Lieberman make the Senate a place where good ideas go to die.

An economic rebound may save imperiled Democrats in 2010 if it happens soon, very soon; it certainly will take hold by 2012. But to borrow from Rahm Emanuel, you never want a serious recovery to go to waste. If the president and his party fail to harness their rescue of the country from Republican-induced disaster to advance big changes, the battle for a new progressive era will be lost. The Democratic Party will continue living off the increasingly distant legacies of Roosevelt and Kennedy while candidates are left to follow hack counsel like that of Democratic Senate Campaign Committee Chairman Robert Menendez, for whom all politics is Jersey: "Just run long and unrelenting negative campaigns against your opponents."

I’m not arguing against being political—or smart. Obama will talk about cutting the deficit—and that will be good politics and, in the long term, good policy. But simply holding onto office is not only an unworthy goal; in the end, it’s also the path to losing it.

So what will Obama do? Slide toward another wasted Democratic presidency? Settle for his own parentheses in the annals of history? Calculate, calibrate and, well, triangulate?

Was Obama elected to be a custodial president—one whose singular historic achievement is his election? I don’t believe that and neither do savvy Republicans, who feared he would be Reagan in reverse.

So, Mr. President, steel yourself and ride out the storm. If you get health care through, clouds will begin to clear. If you fight on for "change we can believe in," you may suffer setbacks, but you will retain the power and the possibility of writing history instead of passively reading it.

And whatever you do, in next week’s State of the Union address, please don’t mention school uniforms.

-

‘Lumpy skin’ protests intensify across France as farmers fight cull

‘Lumpy skin’ protests intensify across France as farmers fight cullIN THE SPOTLIGHT A bovine outbreak coupled with ongoing governmental frustrations is causing major problems for French civil society

-

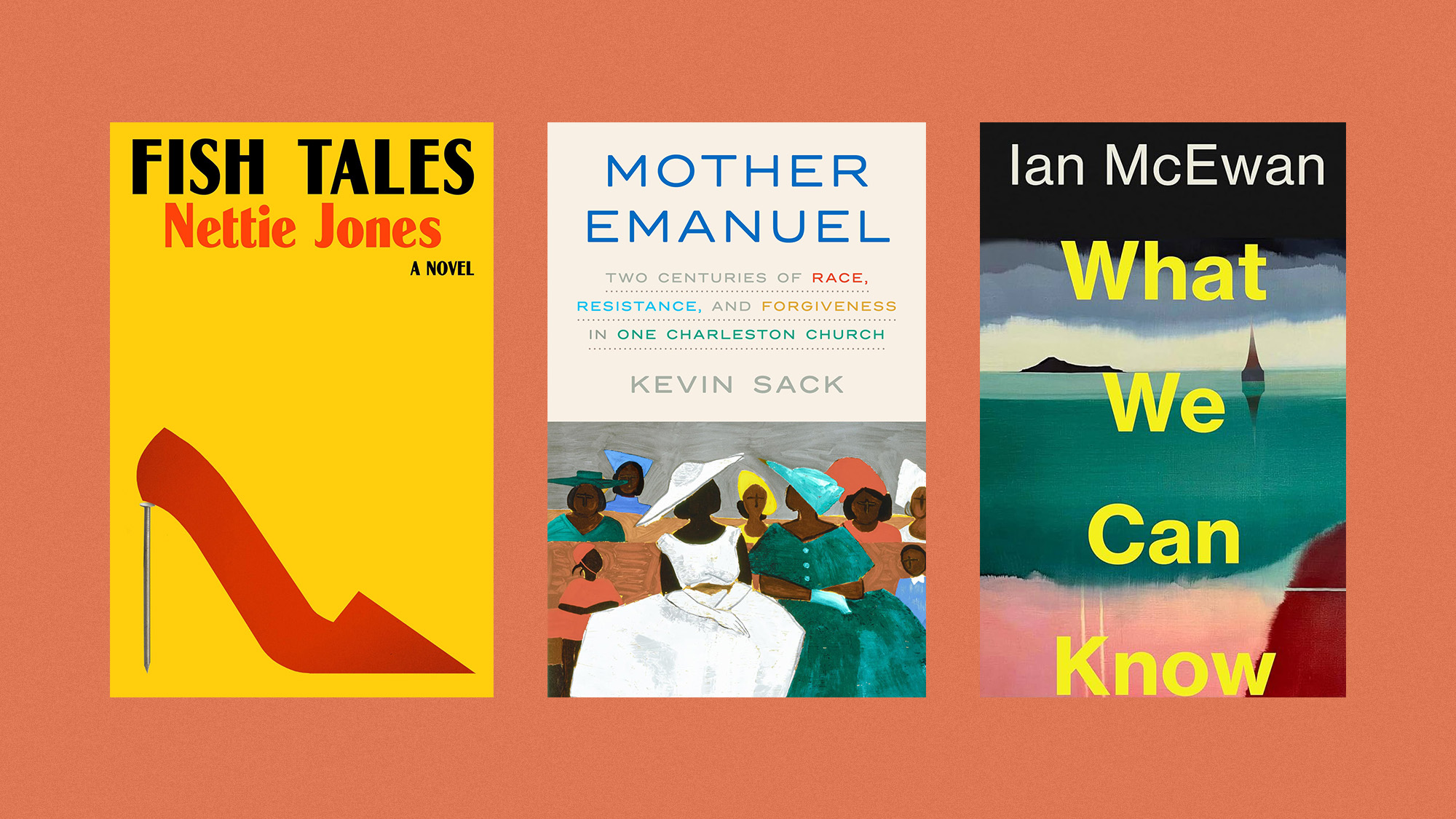

The best books of 2025

The best books of 2025The Week Recommends A deep dive into the site of a mass shooting, a new release from the author of ‘Atonement’ and more

-

Inside Minnesota’s extensive fraud schemes

Inside Minnesota’s extensive fraud schemesThe Explainer The fraud allegedly goes back to the Covid-19 pandemic

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are US billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are US billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration