Obituaries

Robert Craig Knievel and Henry Hyde

The motorcycle daredevil who tried to leap across a canyon

Robert Craig Knievel spent much of his adolescence in the wide-open frontier town of Butte, Mont., raising hell. At 13, he stole his first motorcycle, and later dropped out of high school to work in the copper mines. After he once made an earthmover pop a wheelie, it crashed into Butte’s main power line and blacked out the entire town. Knievel raced stock cars and motorcycles, joined the Army in the late 1950s, and later drifted into a life of petty crime. He got his nickname after being arrested for stealing hubcaps. The police put him in a cell with a local troublemaker known as “Awful Knofel,” and christened their new charge “Evil Knievel.” He later changed the spelling to “Evel,” because it looked classier. He was selling motorcycles in Moses Lake, Wash., when, as a promotional stunt, he jumped 40 feet over parked cars and a box of rattlesnakes, and landed on top of the rattlers. At age 27, he had found his calling—what he later described as “jumping over weird stuff on motorcycles.”

In 1965, Knievel formed a troupe called Evel Knievel’s Motorcycle Daredevils and “began barnstorming Western states,” said The New York Times. Later he went solo, and in 1968 reached the big time with a “much-publicized jump over the fountains at Caesars Palace” in Las Vegas. The stunt turned into a disaster when Knievel lost control of his bike and slammed into a brick wall. The accident left him with a broken pelvis, hips, and ribs, and he remained unconscious for a month. But as soon as he recuperated, he jumped over 52 wrecked cars at the Los Angeles Coliseum.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

A succession of jumps, personal appearances, and product endorsements followed, said the Los Angeles Times. Soon his “fingers were barnacled with diamonds.” Among his possessions were a Rolls-Royce, a Learjet, and a tractor trailer rigged with a bar, dressing room, and storage area for his motorcycles and jumping ramps. In 1974, Knievel blasted off a ramp over Snake River Canyon outside Twin Falls, Idaho, on his steam-propelled Sky Cycle X-2, before 40,000 paying spectators. As he soared 2,000 feet over the canyon floor at 350 miles an hour, his parachute opened prematurely and he drifted anti-climactically to the canyon floor. Other daredevil stunts followed, but as audience interest waned, Knievel succumbed to bouts of depression, drank heavily, and divorced his wife. In 1977, he spent five months in prison for hitting a television executive with a baseball bat.

Knievel’s life as a daredevil also took a serious physical toll. He contracted hepatitis C from a blood transfusion, underwent a liver transplant, and needed a walker because his legs had been fractured so often. His spine was fused and he had a hip replacement, and his arms were so crippled that he needed help to put on a belt. Yet he continued to think big, and as late as 2003, at age 64, talked about making another jump. “I’m a guy who is first of all a businessman,” he said. “I’m not a stuntman. I’m not a daredevil. I’m”—he paused—“I’m an explorer.”

The pro-life congressman who led the fight to impeach Clinton

White-maned, silver-tongued Henry Hyde was just a freshman representative from Illinois when, in 1976, he sponsored the first significant pro-life legislation ever enacted by Congress—a ban on federal spending for abortions that would always be known as the Hyde Amendment. He will also be remembered as the chairman of the House Judiciary Committee who, in 1998, oversaw impeachment proceedings against President Bill Clinton—which Hyde memorably described as “this melancholy procedure.”

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Hyde was born on Chicago’s North Side and “raised as a Democrat in an Irish-Catholic family,” said the Chicago Tribune. By high school, he stood 6-foot-3 and won a scholarship to play basketball at Georgetown. But then World War II intervened, and Hyde served in the Navy instead. His allegiance to the Democratic Party also began to slip during the war. His study of Marxist literature, he later said, convinced him that President Franklin Delano Roosevelt underestimated the threat of communism. In 1949, Hyde graduated from Loyola University Law School in Chicago, and the following year entered private practice, joined the GOP, and began his political career.

Hyde lost a close race for Congress in 1962, said The Washington Post, but five years later was elected to the Illinois House. He soon encountered what would become his “signature issue” when, during his first year in state office, a colleague asked him to co-sponsor an abortion-rights law. Admitting he had never given much thought to the issue, he read up on the matter and decided he was strongly anti-abortion. After he was elected to Congress in 1974, he quickly made a national name for himself as an impassioned abortion foe. He later would become an outspoken defender of the Reagan White House and then–Lt. Col. Oliver North during congressional hearings on the Iran-Contra scandal.

Hyde’s opposition to abortion and his central role in the effort to impeach President Clinton may have defined his public image, said The New York Times. But he was also a “complex political persona” who championed numerous foreign-aid measures, backed Clinton’s proposed ban on assault weapons, supported various child welfare bills, and voted to extend the Voting Rights Act. During the highly contentious impeachment process, it emerged that the married Hyde had himself carried on an affair, during the 1960s. Dismissing the revelation as a Democratic attempt to discredit him, Hyde told reporters, “The statute of limitations has long since passed on my youthful indiscretion,” though he had been in his 40s at the time.

In declining health and able to move around the Capitol only in a wheelchair, Hyde retired last year. He hated to leave public office, Hyde remarked at his retirement dinner. “When I cross the river for the last time,” he said, echoing comments that Gen. Douglas MacArthur made about the Army, “my thoughts will be of the House, the House, the House.”

-

How will China’s $1 trillion trade surplus change the world economy?

How will China’s $1 trillion trade surplus change the world economy?Today’s Big Question Europe may impose its own tariffs

-

‘Autarky and nostalgia aren’t cure-alls’

‘Autarky and nostalgia aren’t cure-alls’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Japan’s Princess Aiko is a national star. Her fans want even more.

Japan’s Princess Aiko is a national star. Her fans want even more.IN THE SPOTLIGHT Fresh off her first solo state visit to Laos, Princess Aiko has become the face of a Japanese royal family facing 21st-century obsolescence

-

R&B singer D’Angelo

R&B singer D’AngeloFeature A reclusive visionary who transformed the genre

-

Kiss guitarist Ace Frehley

Kiss guitarist Ace FrehleyFeature The rocker who shot fireworks from his guitar

-

Robert Redford: the Hollywood icon who founded the Sundance Film Festival

Robert Redford: the Hollywood icon who founded the Sundance Film FestivalFeature Redford’s most lasting influence may have been as the man who ‘invigorated American independent cinema’ through Sundance

-

Patrick Hemingway: The Hemingway son who tended to his father’s legacy

Patrick Hemingway: The Hemingway son who tended to his father’s legacyFeature He was comfortable in the shadow of his famous father, Ernest Hemingway

-

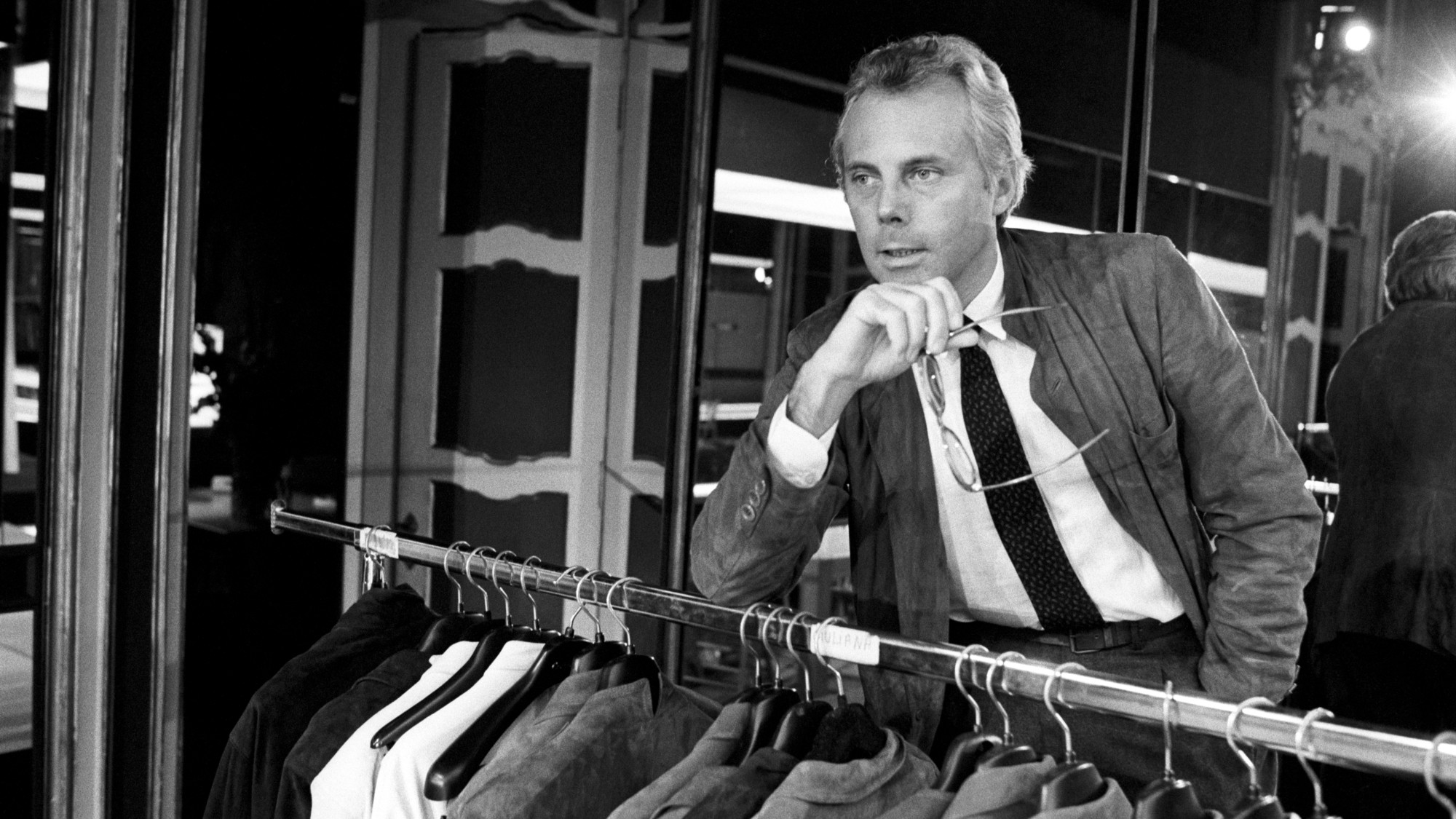

Giorgio Armani obituary: designer revolutionised the business of fashion

Giorgio Armani obituary: designer revolutionised the business of fashionIn the Spotlight ‘King Giorgio’ came from humble beginnings to become a titan of the fashion industry and redefine 20th-century clothing

-

Ozzy Osbourne obituary: heavy metal wildman and lovable reality TV dad

Ozzy Osbourne obituary: heavy metal wildman and lovable reality TV dadIn the Spotlight For Osbourne, metal was 'not the music of hell but rather the music of Earth, not a fantasy but a survival guide'

-

Brian Wilson: the troubled genius who powered the Beach Boys

Brian Wilson: the troubled genius who powered the Beach BoysFeature The musical giant passed away at 82

-

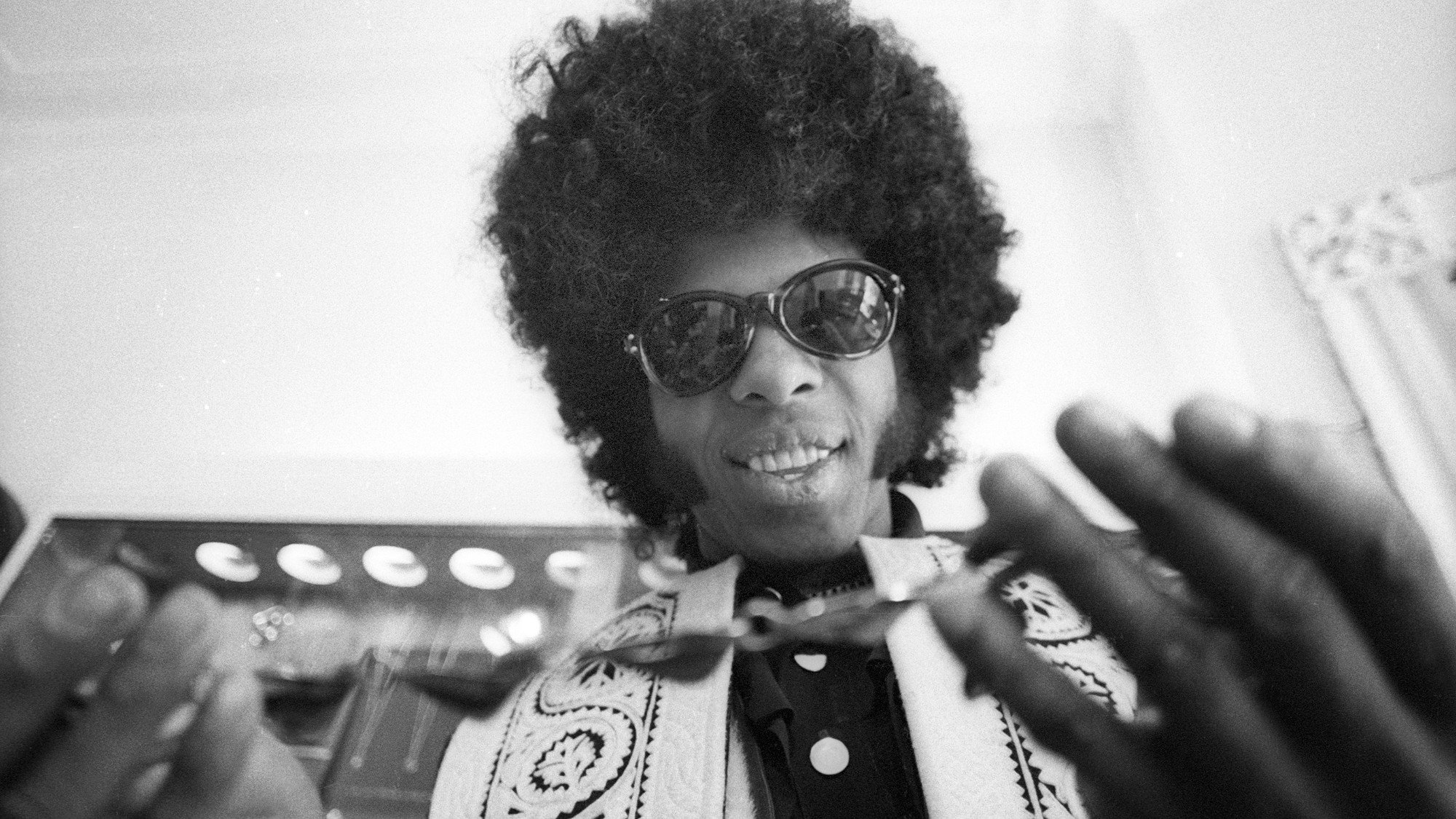

Sly Stone: The funk-rock visionary who became an addict and recluse

Sly Stone: The funk-rock visionary who became an addict and recluseFeature Stone, an eccentric whose songs of uplift were tempered by darker themes of struggle and disillusionment, had a fall as steep as his rise