Yemen's descent into chaos

The U.S. recently closed its embassy in Yemen, after Houthi rebels took the capital. Where is the country headed?

Why is Yemen such a mess?

Yemen, the poorest Arab country, has never been stable. It was formed in 1990 after multiple wars between the two distinct nations of North Yemen, once part of the Ottoman Empire, and South Yemen, a former British colony later allied with the Soviet Union. The country is inherently unbalanced, since the oil reserves are in the south, while the political clout is centered in the north. Various tribes control turf in both regions. The south launched a brief civil war against the north in 1994 and sporadic rebellions since, while northern tribes — including the Houthis — have battled among themselves. The lawlessness and poverty make the country ripe for extremist recruiting. In 2009, Islamist terrorists there created a group they called al Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula.

What has this al Qaida group done?

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Its list of attacks on U.S. interests is long. In 2000, al Qaida militants bombed the USS Cole in the Yemeni port of Aden, killing 17 sailors and injuring 39. Anwar al-Awlaki, a U.S. citizen born in New Mexico to Yemeni immigrants, fled to Yemen in 2004 after being investigated for connections to the 9/11 attackers. There he became involved with a terrorist cell that radicalized failed underwear bomber Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, Fort Hood shooter Nidal Malik Hasan, and accused Boston Marathon bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev. In 2011, al-Awlaki became the first American citizen to be assassinated by a CIA drone strike. The English-language online al Qaida magazine Inspire that al-Awlaki helped set up is still based there, urging Muslims to engage in jihad. The Yemeni government, under Ali Abdullah Saleh and then under Abed Rabbo Mansour Hadi, has long opposed and fought al Qaida, and cooperated with U.S. drone strikes on militants. Now that the Houthis are in charge, that cooperation is in jeopardy.

Who are the Houthis?

Led by the al-Houthi family, they now head the Shiite Zaydi sect, a minority in the mainly Sunni country. Zaydis trace their lineage to the Prophet Mohammed, and they have ruled the northern Yemeni highlands for centuries. After Yemen was formed, the Houthis felt that Saleh marginalized their sect and usurped control of their territory. So in the early 2000s they took to arms, battling Saleh's forces with little success. Their big chance came with the Arab Spring in 2011, when Sunni Islamists, pro-democracy students, and southern Sunni tribes joined forces with the Houthis and held massive protests calling for Saleh to step down. But when Saleh's vice president, Hadi, took over, Houthis believed they had been shut out of the power-sharing agreement. They soon took up arms again and have now driven Hadi from power and taken over the capital.

Who are their allies?

That's unclear. The Houthis hate the U.S. — part of their slogan is "Death to America, death to the Jews" — but they also oppose the Sunni extremists in al Qaida. Still, in the chaos that is Yemen, alliances can shift quickly. Some Western analysts believe that the Houthis are getting weapons and money from Shiite Iran. Strangely enough, some Yemeni analysts say the Houthis have been backed at least tacitly by their old enemy Saleh. The ex-president was furious with his successor, Hadi, for abolishing the Republican Guard, a powerful militia headed by Saleh's son Ahmed. Western diplomats and Yemeni politicians say that Saleh is plotting to return as the national leader and has made a deal with the Houthis to help him do that.

Can the Houthis stabilize the country?

Probably not. Last week, the U.N. brokered a power-sharing accord between the Houthis and other parties, with a legislature that allocates some seats to all the various tribes. But the scheme looks shaky, and it's unclear whether Yemen's Sunni neighbors will allow the Shiite minority group to retain so much power. The Gulf Cooperation Council has said it wants the U.N. to authorize military force to reverse what it calls "the Houthis' illegitimate seizure of power," saying that the GCC states of Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain, Oman, and the United Arab Emirates might intervene.

What does this mean for the U.S.?

The continued chaos is breeding even more extremism. The Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, or ISIS, has started recruiting in several Yemeni towns, and some al Qaida supporters have reportedly switched allegiance to ISIS. But al Qaida is still the main threat. The Houthi coup has actually helped al Qaida's propaganda efforts in Yemen, since the terrorist group can portray itself as the guardian of the Sunni majority against the Shiite usurpers. "The Houthi takeover has resulted in al Qaida's best recruitment drive in years," said analyst Ahmed al-Zurqa. While the U.S. has shut its embassy in Sanaa, it hasn't withdrawn special forces on the ground, and drone strikes against al Qaida targets are continuing. Yemen may not have a functioning central government, but it still has an independent army, and U.S. forces are still training and conducting missions with Yemeni soldiers. "We're monitoring [Yemen] every single day," said Pentagon spokesman Rear Adm. John Kirby, "if not every single hour."

The U.S.'s deadly drone war

The U.S. has launched more than 100 drone strikes in Yemen since 2002, killing close to 900 militants, including Anwar al-Awlaki, whom U.S. counterterrorism officials called "the most dangerous man in the world.'' But dozens of civilians have also died. While most Yemenis want to see al Qaida driven from their territory, the strikes have stoked strong anti-American feeling. President Obama said missiles are fired only when there is "near certainty that no civilians will be killed or injured," but from the air, it can be difficult, if not impossible, to discern every person's identity. Many Yemenis believe that the Saleh and then Hadi governments often gave the U.S. names of their political enemies and identified them as terrorists. "Every time they kill an innocent person," said drone victims' advocate Mohamed al-Qawli, "they motivate the families to join al Qaida."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

Anne Hillerman's 6 favorite books with Native characters

Anne Hillerman's 6 favorite books with Native charactersFeature The author recommends works by Ramona Emerson, Craig Johnson, and more

-

How Zohran Mamdani's NYC mayoral run will change the Democratic Party

How Zohran Mamdani's NYC mayoral run will change the Democratic PartyTalking Points The candidate poses a challenge to the party's 'dinosaur wing'

-

Book reviews: '1861: The Lost Peace' and 'Murderland: Crime and Bloodlust in the Time of Serial Killers'

Book reviews: '1861: The Lost Peace' and 'Murderland: Crime and Bloodlust in the Time of Serial Killers'Feature How America tried to avoid the Civil War and the link between lead pollution and serial killers

-

'Once the best in the Middle East,' Beirut hospital pleads for fuel as it faces shutdown

'Once the best in the Middle East,' Beirut hospital pleads for fuel as it faces shutdownSpeed Read

-

Israeli airstrikes kill senior Hamas figures

Israeli airstrikes kill senior Hamas figuresSpeed Read

-

An anti-vax conspiracy theory is apparently making anti-maskers consider masking up, social distancing

An anti-vax conspiracy theory is apparently making anti-maskers consider masking up, social distancingSpeed Read

-

Fighting between Israel and Hamas intensifies, with dozens dead

Fighting between Israel and Hamas intensifies, with dozens deadSpeed Read

-

United States shares 'serious concerns' with Israel over planned evictions

United States shares 'serious concerns' with Israel over planned evictionsSpeed Read

-

Police raid in Rio de Janeiro favela leaves at least 25 dead

Police raid in Rio de Janeiro favela leaves at least 25 deadSpeed Read

-

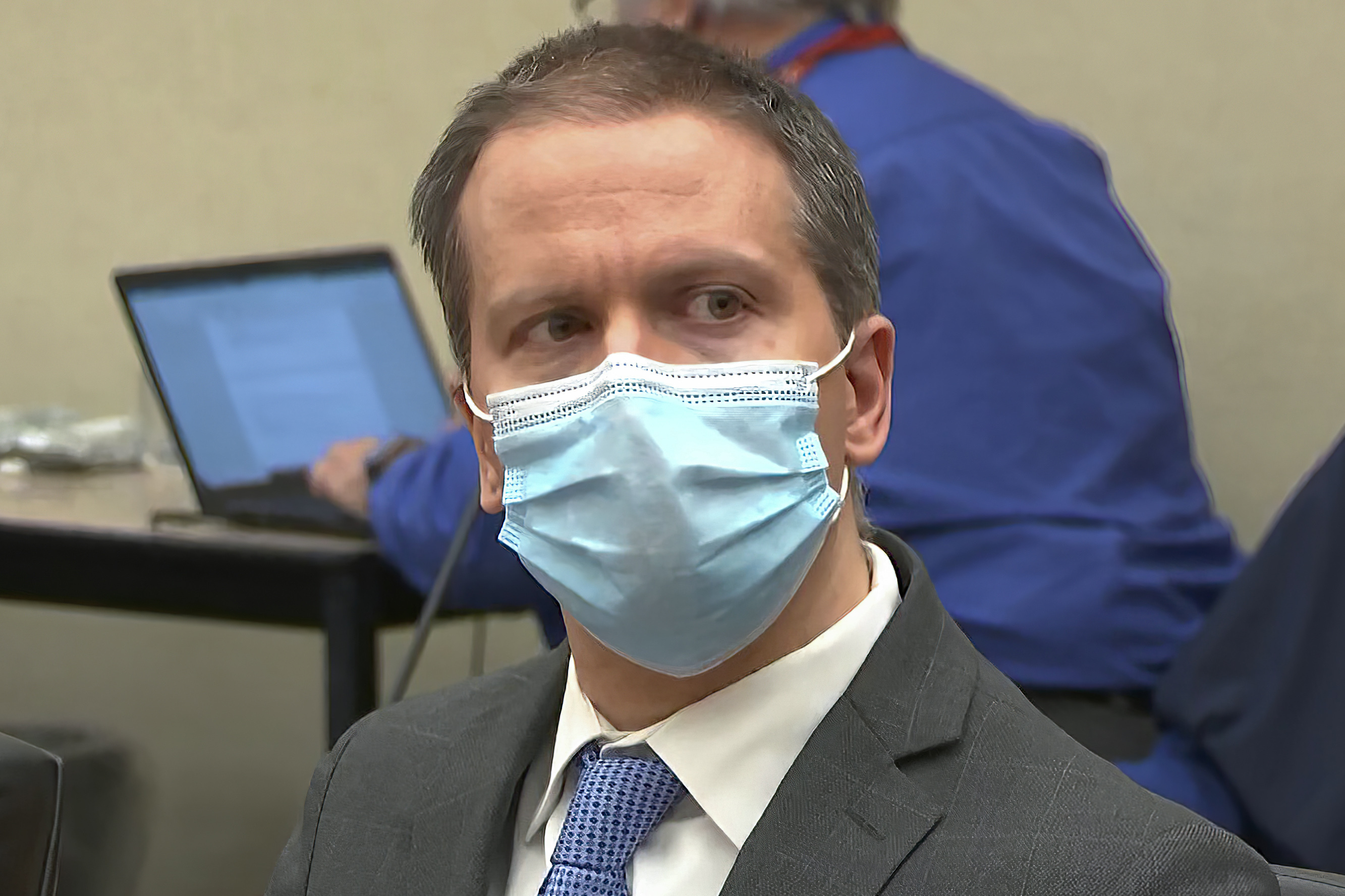

Derek Chauvin's attorney files motion for new trial

Derek Chauvin's attorney files motion for new trialSpeed Read

-

At least 20 dead after Mexico City commuter train splits in overpass collapse

At least 20 dead after Mexico City commuter train splits in overpass collapseSpeed Read