America is running out of soil

Farmland is eroding at 10 times the rate it's being naturally replenished. This is a huge deal.

Roman historian Marcus Cato was a politician, writer, and soldier. He wrote seven volumes on the history of the republic, led Roman armies, and lent his name to his great-grandson, the philosopher Cato the Younger. But, amid all this, Marcus Cato also found time to look at the ground beneath his feet.

One of his most popular writings was a set of advice for farmers, which lays out more than 10 different types of earth — heavy, warm, dry, chalky, marshy, damp, with fog, without fog — and the plants that go in it. A man who would look after the budget and military strategy of one of the world's biggest empires devoted pages to the different patches of soil on a farm, and discussed planting with the same detail as a war plan. His writing was a big hit.

This is because Rome, despite its innovative architecture and globe-spanning military and political experiments, couldn't escape the reality that has dogged all empires, then and today: Its people needed to eat. And, just like today, much of the food on the planet came from farming, which in turn depended on healthy soil and plentiful crops, something even statesmen like Marcus Cato knew all too well.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

And when the Roman empire faded, soil had something to do with it, said David Montgomery, a geologist at the University of Washington and author of Dirt: The Erosion of Civilizations.

Like the Greeks and other powers before them, the Roman empire collapsed for a host of reasons, but underlying much of their troubles was overworked, exhausted, and eroded farmland which strained their ability to feed their citizens. As Montgomery writes, "Rome did not so much collapse as consume itself."

Soil, it seems, has a larger hand in history than it may appear.

"The way people treat land sets the time scale in which it is able to treat people well back in return," Montgomery said. "I don't think there was a society where soil erosion was the only factor that took it out. But it's the template upon which many of the things we think of as history play out."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

So could America go the way of Rome, with its farmland degraded, eroded, and washed away?

To answer that, it's helpful to understand what soil is — and does — in the first place. Soil is not simply dirt, but actually a combination of living organisms, nutrients, and rock and other minerals that scientists consider a sort of outer layer over the bedrock of the planet. And it's a busy environment, providing habitat for plants and animals while helping regulate the flow of water and temperature.

The problem arises when soil that is left exposed to the elements erodes away under heavy rain or wind, washing into rivers or blowing into the sky. This is the kind of erosion that is common when fields are left fallow or forests are clear-cut for agriculture or grazing. It takes an average of 20 years for less than a millimeter of soil to naturally replenish itself, according to a 2006 study from Cornell University, so this type of erosion can undo decades of natural processes. And that's compounded by the risk of soil degradation from agricultural chemicals like pesticides and fertilizers, which can kill the organisms living in the earth.

In the United States alone, soil disappears 10 times faster than it is naturally replenished, according to the Cornell study, at an estimated rate of nearly 1.7 billion tons of farmland alone per year. And it comes at a financial cost, too, with the American economy losing roughly $37 billion in productivity annually from soil loss.

"There's nowhere near enough attention being paid to this issue," Montgomery said. "It's one of the key long-term issues that human society is going to have wrestle with in the next half century. We need to figure out how to turn those trends around."

A 2011 report from the Environmental Working Group argues that even current data may be underestimating the total loss of soil in the country's heartland, where rainstorms wash away earth on heavily tilled farmland. That soil, then, washes into the Mississippi River and onwards to the Gulf of Mexico, where the chemicals used for farming contribute to "dead zones" in the water, according to the study.

And what's happening in America mirrors a worldwide trend. The United Nations named 2015 the International Year of Soils in an attempt to raise awareness of the soil crisis, which they say has degraded 33 percent of the world's soil. With the world's population set to reach nine billion by 2050, the UN warns that food production from agriculture needs to increase by 60 percent just to meet the projected demand, a tall order if soil damage continues.

The threat may be so stark that leading UN officials told reporters last December that most of the soil relied upon by farmers could become so eroded or chemically degraded that it will disappear over the next 60 years.

But initiatives among American farmers might be slowing the losses. New farming practices like terraces and temporary "cover" crops have helped lower soil erosion by more than 40 percent over the past two decades, according to a report from the Soil Science Society of America. Organizations like The Land Institute and American Farmland Trust are helping farmers find low-cost conservation alternatives.

Even the U.S. Farm Bill, legislation governing agriculture which the Congress passes every five years, has begun emphasizing the importance of conservation and soil protection. The 2014 Farm Bill required farmers who take advantage of many government programs to plant according to conservation guidelines.

For his part, Montgomery isn't ready to consign the United States to the fate of history just yet. He recently returned from a visit with farmers in South Dakota, in a region hit hard by the Dust Bowl storms of the 1930s. Today, he said, farmers have converted many of their operations to make little impact on the soil, helping cut down on erosion and the use of chemicals.

And research, including his own, is ongoing into not only keeping soil intact in the ground but ensuring that it stays productive, which means more people have the chance to be fed into the future.

"I believe we do have time to fix it, but we also have a moral obligation to the future to fix it," he said. "This is our last chance to get it right. If the world makes the same mistakes that Rome made, what's the next act? It's not going to be pretty."

Matt Hansen has written and edited for a series of online magazines, newspapers, and major marketing campaigns. He is currently active in press freedom and safety research with Global Journalist Security.

-

Rothermere’s Telegraph takeover: ‘a right-leaning media powerhouse’

Rothermere’s Telegraph takeover: ‘a right-leaning media powerhouse’Talking Point Deal gives Daily Mail and General Trust more than 50% of circulation in the UK newspaper market

-

The US-Saudi relationship: too big to fail?

The US-Saudi relationship: too big to fail?Talking Point With the Saudis investing $1 trillion into the US, and Trump granting them ‘major non-Nato ally’ status, for now the two countries need each other

-

Sudoku medium: November 30, 2025

Sudoku medium: November 30, 2025The daily medium sudoku puzzle from The Week

-

Femicide: Italy’s newest crime

Femicide: Italy’s newest crimeThe Explainer Landmark law to criminalise murder of a woman as an ‘act of hatred’ or ‘subjugation’ but critics say Italy is still deeply patriarchal

-

Brazil’s Bolsonaro behind bars after appeals run out

Brazil’s Bolsonaro behind bars after appeals run outSpeed Read He will serve 27 years in prison

-

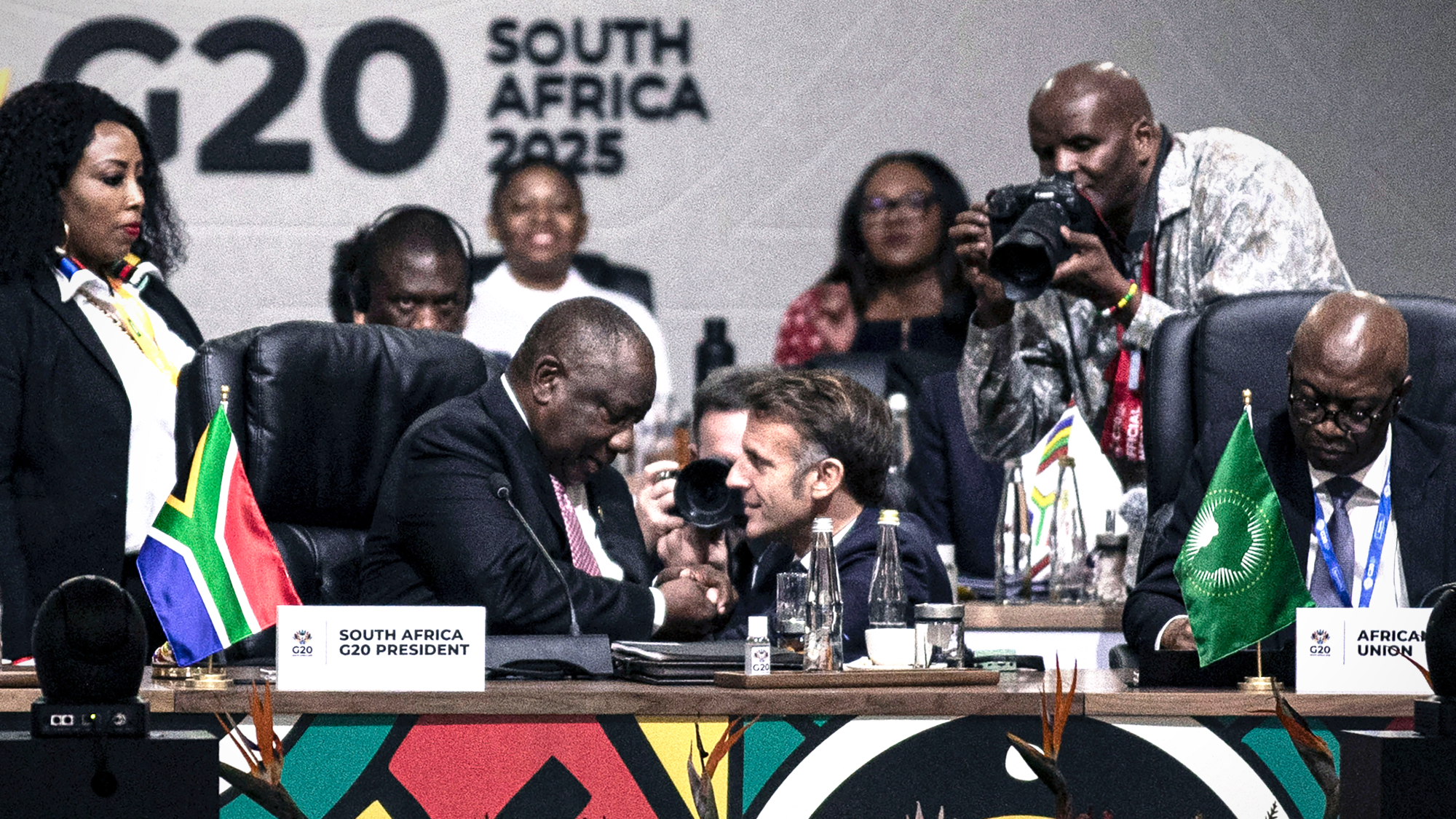

South Africa wraps up G20 summit boycotted by US

South Africa wraps up G20 summit boycotted by USSpeed Read Trump has been sparring with South Africa in recent months

-

Americans traveling abroad face renewed criticism in the Trump era

Americans traveling abroad face renewed criticism in the Trump eraThe Explainer Some of Trump’s behavior has Americans being questioned

-

Nigeria confused by Trump invasion threat

Nigeria confused by Trump invasion threatSpeed Read Trump has claimed the country is persecuting Christians

-

Ukraine: Donald Trump pivots again

Ukraine: Donald Trump pivots againIn the Spotlight US president apparently warned Volodymyr Zelenskyy to accept Vladimir Putin’s terms or face destruction during fractious face-to-face

-

Sanae Takaichi: Japan’s Iron Lady set to be the country’s first woman prime minister

Sanae Takaichi: Japan’s Iron Lady set to be the country’s first woman prime ministerIn the Spotlight Takaichi is a member of Japan’s conservative, nationalist Liberal Democratic Party

-

Russia is ‘helping China’ prepare for an invasion of Taiwan

Russia is ‘helping China’ prepare for an invasion of TaiwanIn the Spotlight Russia is reportedly allowing China access to military training