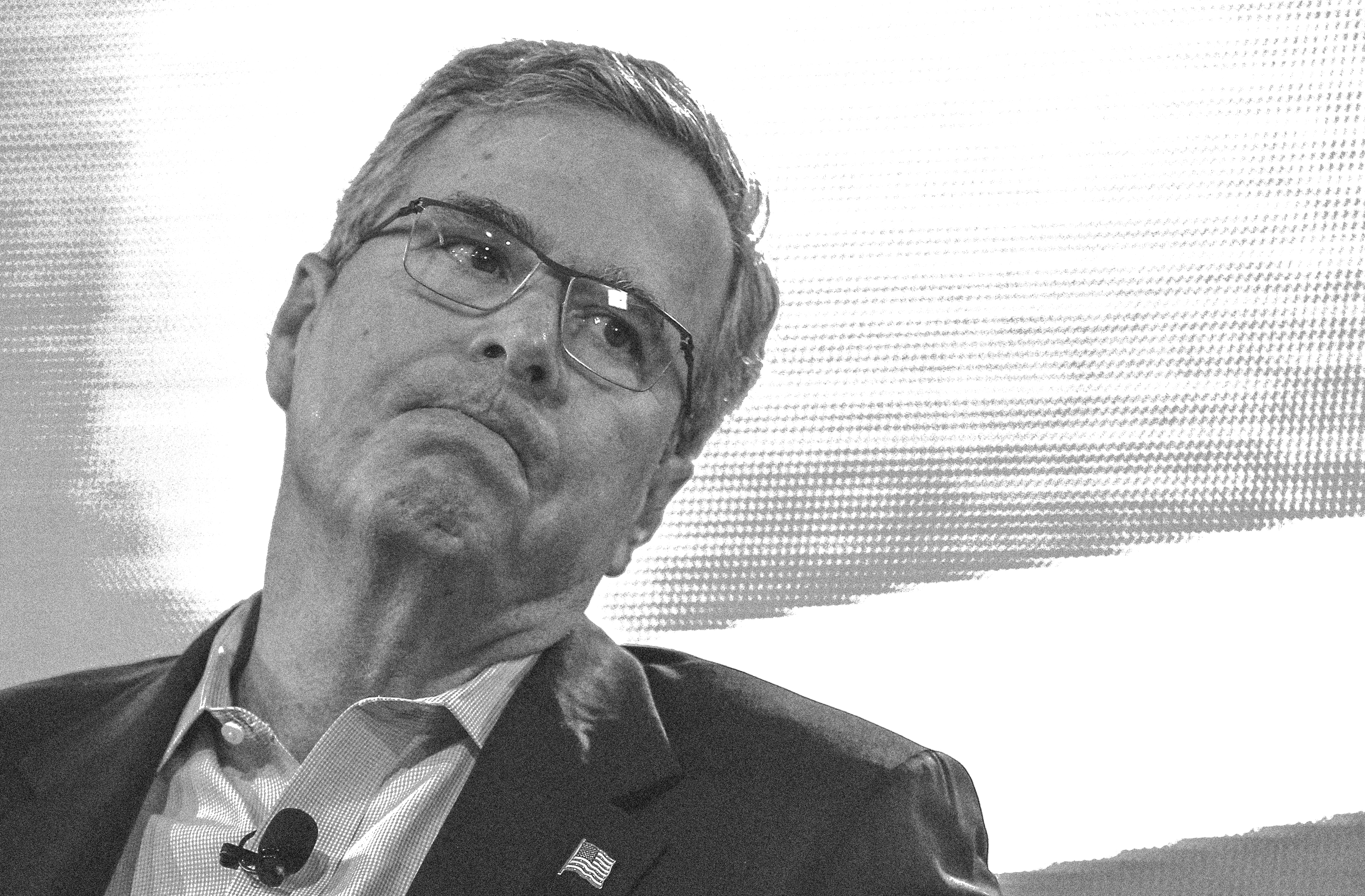

How Jeb Bush blundered into making the Iraq war his problem

An honest answer would have saved Bush a lot of heartache

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Jeb Bush has taken three attempts at answering the following question: "Knowing what we know now, would you have authorized the invasion of Iraq?"

Here are my three translations of his answers:

First attempt: Of course, I would bring about the same disaster for my nation and several others. Did you think I was going to disrespect my brother?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Second attempt: Well, I don't know what I would have done about Iraq. Hypotheticals only tell us that we can't really know anything for sure. Did you really think I was going to disrespect the laws of logic and epistemology?

Third attempt: Actually, I can't answer hypothetical questions because so many people paid the ultimate sacrifice. Did you really think I was going to disrespect our dead soldiers?

Feel free to check the above against the originals. In fact, it was even worse than that, with him adding, "The simple fact is mistakes were made, and we need to learn from mistakes of the past to make sure we're strong and secure going forward."

Besides being the most shopworn cliché of moral cowardice, "mistakes were made" is not even an answer an insurance agent would accept for a home flood. Why should we accept it from a man who has the benefit of hindsight and the ambition to be commander-in-chief?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

It is a little disconcerting that Jeb Bush, who has so far run the smoothest, most professional, and well-conceived campaign in the Republican field, has given so little thought to the most easy-to-anticipate policy question about making another Bush president.

Let's take his first attempt. Bush is essentially more loyal to his brother's legacy than his own brother is. In a rare moment of near candor for a presidential autobiography, George W. Bush wrote about his own anguish over the war, given what we now know. "No one was more shocked or angry than I was when we didn't find the weapons. I had a sickening feeling every time I thought about it," he wrote. "I still do."

Peter Baker's sympathetic treatment of Bush's time in office portrayed him as disillusioned with the unanimous advice of the members of his administration, none of whom expressed any doubts whatsoever about the decision to go to war. This disappointment was sharply aimed at Dick Cheney.

Jeb Bush's third attempt is perhaps his most egregious. In fact, what is most disrespectful to soldiers is not silence about how they and their friends might be used. Respect for the living and the dead requires the kind of reflection that Bush now disavows.

As for hypotheticals: The easiest and politically safest option is to coach Jeb Bush into saying something like this: "Barack Obama should have negotiated an agreement that would have allowed U.S. troops to stay and nip ISIS in the bud. But if you're asking me if the world is better off without Saddam Hussein…" and then trail off into the obvious, empty-calorie rhetoric about American leadership that the nation grows fat on in every election.

But for a moment, let's just think through the different hypotheticals and consider what an honest answer would have looked like. We don't really know if the world is better off without Saddam Hussein. And we certainly know that we would have been better off if we hadn't launched a war to remove his government.

If Hussein really was the madman the last Bush administration claimed him to be, sure, we could absolve ourselves. If Hussein was a key player in the 9/11 plot, if he was rapidly developing weapons of mass destruction that could deliver a mushroom cloud on United States soil, if he regularly made use of a human shredder machine for sport, absolutely, the world would be better off without him.

These were lies. Hussein was just another awful Middle Eastern autocrat, a man whose state was gelded by a no-fly-zone, a dictator with an expansive taste in '80s tween erotica. But he was also a holdover of Baathist pan-Arabism, serving as a counterweight to Iran's regional ambitions and an obstacle to Sunni radicalism. So, no, we don't know that the whole world is actually better off without him.

But I do know that after the war in Iraq America's credibility, its military capability, and its military personnel and their families, not to mention Iraq's religious minorities, the Sunni Triangle, and Northern Syria, are worse off than they otherwise would have been. And I wait for a Republican candidate to say as much, and as clearly.

Michael Brendan Dougherty is senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is the founder and editor of The Slurve, a newsletter about baseball. His work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, ESPN Magazine, Slate and The American Conservative.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred