No, your brain isn't a computer

The workings of the brain are far more wondrous than those of a MacBook Pro

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Hey, I have a question for you.

Is your brain a Toshiba Satellite C55-C5240 (Amazon's bestselling laptop)?

Or is it a sleek, user-friendly, slightly overpriced MacBook Pro?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Or perhaps some custom-built hot rod powered by Intel's Core i7-5960X Extreme Edition chip, one of the fastest processors you can buy? (You attended an Ivy League school, didn't you?)

As for me, my brain is obviously the Tianhe-2, arguably the most powerful supercomputer in the world. (Unfortunately, this means my brain resides in China.)

These playful, if not absurd, thoughts were prompted by a recent New York Times op-ed by Gary Marcus, a professor of psychology and neural science at New York University. Marcus' argument is perfectly captured by his essay's declarative title, "Face It, Your Brain Is a Computer." In fairness, Marcus says explicitly that he doesn't necessarily mean the types of computers we use in our daily lives: "The brain is obviously not a Macintosh or a PC." Yet he does mean some kind of computer.

And that's what's truly absurd.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

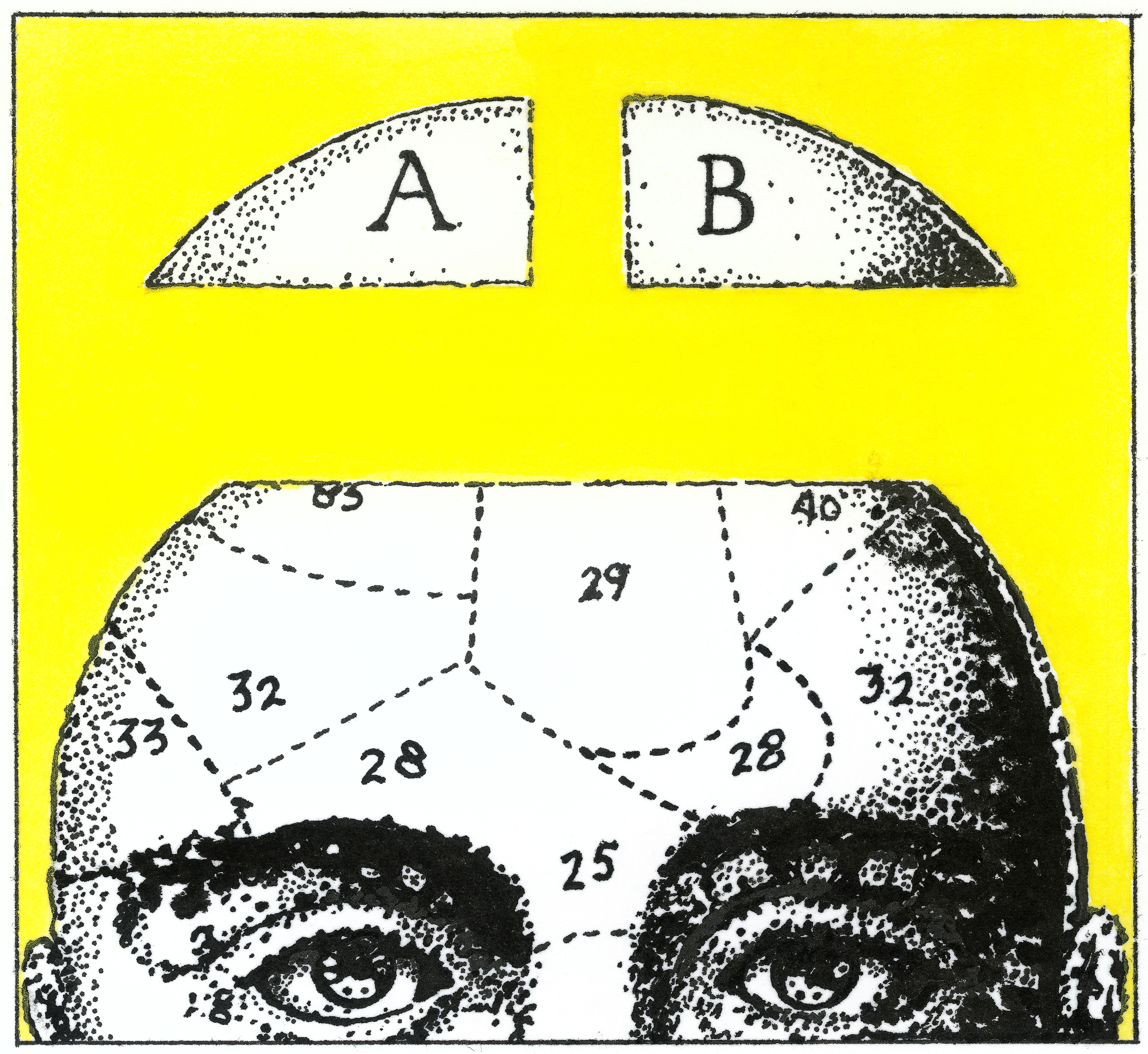

At some level, Marcus knows this. Why else would he start off the op-ed by pointing out how common it is for thinkers down through the ages to model the brain on the latest technological innovations of their time? There's René Descartes, writing in the early 17th century, who thought of the brain as "a kind of hydraulic pump, propelling the spirits of the nervous system through the body." There's Sigmund Freud, who roughly a century ago compared the brain to a steam engine. More recently, neuroscientist Karl Pribram proposed that the brain might be a "holographic storage device." Yet Marcus pushes forward, insisting that his computer-age analogy is somehow different than the scientific misfires of earlier eras.

Actually, it isn't. Not even close. And it's astonishing that someone who devotes his life to studying the brain could end up persuaded otherwise. The brain isn't a computer, or meaningfully like a computer. Indeed, it's not like any bit of technology any human being has ever devised.

To see this, one need only open oneself to experience in all of its wondrousness and compare it to what experience would be like for a brain modeled exclusively on even extraordinarily complicated computations.

Marcus proposes that the brain might "consist of highly orchestrated sets of fundamental building blocks, such as 'computational primatives' for constructing sequences, retrieving information from memory, and routing information between different locations in the brain." But human experience isn't (or isn't simply) a product of "information" being sorted, combined, and compared in various, complicated ways. If it were, experience would consist of a sequence of discrete perceptions of sense data divided into classes (gray, warm, soft). But that's not what experience is like at all. Instead, we experience kinds of beings or things that possess those characteristics (a cuddly cat named Fluffy, say).

Now, Marcus would probably reply that in an age when computers can run facial recognition software — with the software continually improving — it is perfectly possible, even easy, to imagine our computer-brains absorbing sense data, breaking it into classes, drawing on a vast store of memories, and then unifying all of it into the ability to recognize specific kinds of beings or things.

But this misses the character or texture of experience entirely, reducing it to what a robot or other type of machine would "experience." In order to get fully human experience, all of these complex computations must be combined with a living body that brings a personal concern to its experience of the world.

The great philosophical and religious traditions of the West use the term "soul" to describe this extra something in us that transcends mere computation. One need not presume this soul is immortal or in any way separable from the body or brain. The soul in this sense is merely the seat of a living being's concern for its own good.

It is this concern for my own good that lights up a lived world of connection and meaning. I experience Fluffy not as a conglomeration of sense data and class characteristics that, when combined with memory, I can identity as a familiar entity named Fluffy. Rather, I experience a being that has those characteristics, that is somehow more than those characteristics. This being is something more, something ineffable, something that can't really be put into words, and certainly not into the factual, discursive statements a computer can make sense of. (Poetry comes closest to capturing it, though it still falls short of conveying the experience of beings in all their richness.)

The key to this experience is what the cat means to me, its contribution to my own good and the good of my world — a world that is itself the totality of beings that concern me because they contribute in varying ways to the goods I embrace, seek out, and pursue in my life. My cat benefits me and my world in innumerable ways — giving me (among many other things) joy, companionship, love, affection, a sensation of coziness.

And these goods are intertwined in indescribably complex ways with other goods in my life — laughing at Fluffy with my wife and kids, enjoying a sensation of contentment from him snoozing and purring on my lap as I write my column, feeling a mixture of gratitude and disgust when he brings me a dead mouse that otherwise might have ended up scurrying across my kitchen floor.

What about Fluffy's experience of the world? If a human brain is just a very complex computer, then it would seem that the much less sophisticated brain of a cat would be a much less sophisticated computer — one much closer to the kinds of computers we know and use all the time.

And yet that's not the case at all. Fluffy's capacity to divide sense data into class characteristics is more primitive or elemental, and he is certainly less capable of communicating his thoughts. But like me, he has a soul (in the sense invoked above). Fluffy knows, in some real sense, who I am — not just as a list of characteristics but as a being that matters to him in a specific way. I feed him, pet him, bring him to the vet when he's injured or sick (though it's doubtful he's capable of recognizing this unpleasant and frightening experience as benefiting him).

I'm able to matter to Fluffy in this way because a cat is a living being with an intuitive, pre-verbal (human infants have it, too) awareness of its own good — a good to which I significantly contribute.

Which means that my cat's brain is no more a computer than yours and mine.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

Can Europe regain its digital sovereignty?

Can Europe regain its digital sovereignty?Today’s Big Question EU is trying to reduce reliance on US Big Tech and cloud computing in face of hostile Donald Trump, but lack of comparable alternatives remains a worry

-

The Mandelson files: Labour Svengali’s parting gift to Starmer

The Mandelson files: Labour Svengali’s parting gift to StarmerThe Explainer Texts and emails about Mandelson’s appointment as US ambassador could fuel biggest political scandal ‘for a generation’

-

Magazine printables - February 13, 2026

Magazine printables - February 13, 2026Puzzle and Quizzes Magazine printables - February 13, 2026