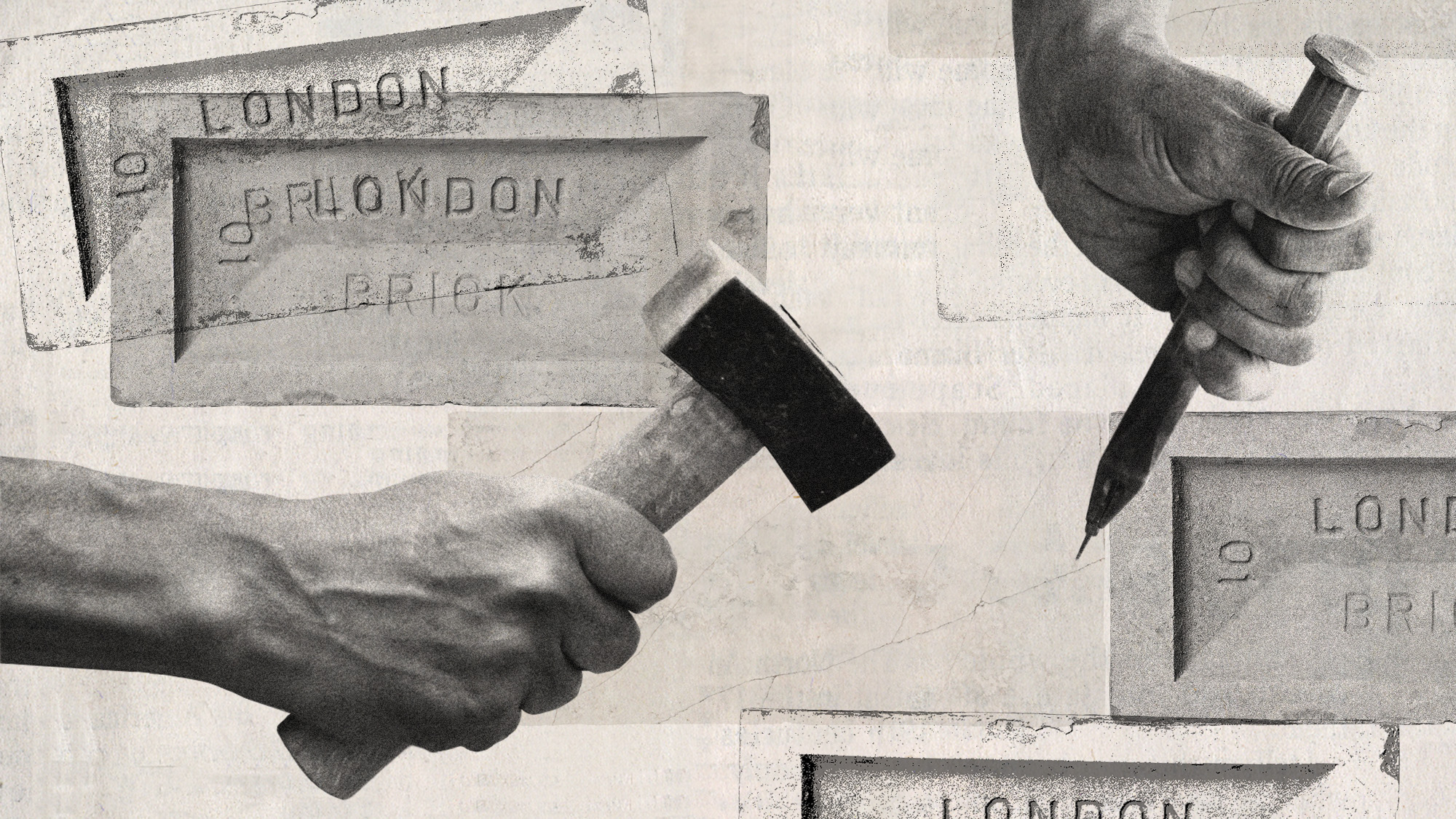

Builders return to the stone age

With bricks becoming ‘increasingly unsustainable’, could a reversion to stone be the future?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Stone is “making a comeback” in the building industry after years of being “forgotten”, said the BBC. With clear benefits to the environment, such as a lower carbon footprint than other traditional materials, the substance’s popularity is growing as a more sustainable, and nostalgic, alternative.

In warmer climates, stone is valued for its cooling properties, but the benefits of stone in the UK could be much more varied.

‘Tangible link’ to the past

The rise in demand seems to be particularly welcome north of the border. Scotland’s identity is “closely linked to its stone-built heritage”, said Historic Environment Scotland. Stone infrastructure is not only a “tangible link” to the country’s past, but it also stimulates financial opportunities. Millions of tourists see stonework, and the traditional aesthetic of stone walls and buildings as a “huge draw”, and their arrival provides a “vital source of income” for local economies.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In rural areas, stone walling and stone building have long histories, dating as far back as 5,000 years, said Jennie Rothenberg Gritz in Smithsonian. Stonewalling uses stones, “carefully fitted together in such a way that the wall won’t fall down” without any mortar or cement. This means that if you have to fix one section, the whole wall remains secure, whereas “when a mortared wall cracks, the entire wall is in peril”.

“What price do you put on forever?”, stone wall expert Kristie de Garis told the magazine. “Mortared walls need to be redone roughly every 15 to 30 years. But there are dry stone walls still standing after thousands of years.”

‘Renaissance’ fuelled by sustainability

The most important aspect of stone is probably its “ecological value”, said Christiane Fath in World-Architects.com. Though it has always been popular and used in some of the most famous buildings in the world – think Cologne Cathedral, the Colosseum, or Notre Dame – in the era of climate change, stone is heading for a “renaissance” after major developments in Germany, specifically Cologne, Leipzig and Berlin.

Its benefits are manifold, wrote Fath. Created by natural processes, its production “consumes little energy”, and its “buildings can be recycled” if approached intelligently. Stone building’s human input should not be overlooked: despite the use of machinery in its production, the creation of stone elements is still an “artisan process” providing “additional cultural value”, and is a celebration of timeless craftsmanship.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

“Building in brick is increasingly unsustainable”, said Amy Frearson in the FT. Processing bricks involves additional ingredients like lime, sand, and cement, even before the “energy cost of firing and shipping”. Sustainability aside, stone is a way of “delivering the very local character that the government wants” when developing houses, something which is important to local councils.

One major drawback of turning to stone as a material is the problem of “perception”, said the broadsheet. Added to the higher cost, and despite its strong load-bearing capacity, stone has cultivated a “luxury surface finish” image. This drives stringent demand for “uniform varieties”, “leaving anything short of perfect to be rejected and creating a lot of surplus”.

Will Barker joined The Week team as a staff writer in 2025, covering UK and global news and politics. He previously worked at the Financial Times and The Sun, contributing to the arts and world news desks, respectively. Before that, he achieved a gold-standard NCTJ Diploma at News Associates in Twickenham, with specialisms in media law and data journalism. While studying for his diploma, he also wrote for the South West Londoner, and channelled his passion for sport by reporting for The Cricket Paper. As an undergraduate of Merton College, University of Oxford, Will read English and French, and he also has an M.Phil in literary translation from Trinity College Dublin.

-

Political cartoons for February 15

Political cartoons for February 15Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include political ventriloquism, Europe in the middle, and more

-

The broken water companies failing England and Wales

The broken water companies failing England and WalesExplainer With rising bills, deteriorating river health and a lack of investment, regulators face an uphill battle to stabilise the industry

-

A thrilling foodie city in northern Japan

A thrilling foodie city in northern JapanThe Week Recommends The food scene here is ‘unspoilt’ and ‘fun’

-

The environmental cost of GLP-1s

The environmental cost of GLP-1sThe explainer Producing the drugs is a dirty process

-

Zero-bills homes: how you could pay nothing for your energy

Zero-bills homes: how you could pay nothing for your energyThe Explainer The scheme, introduced by Octopus Energy, uses ‘bill-busting’ and ‘cutting-edge’ technology to remove energy bills altogether

-

Why scientists want to create self-fertilizing crops

Why scientists want to create self-fertilizing cropsUnder the radar Nutrients without the negatives

-

Why the Middle East is obsessed with falcons

Why the Middle East is obsessed with falconsUnder the Radar Popularity of the birds of prey has been ‘soaring’ despite doubts over the legality of sourcing and concerns for animal welfare

-

‘Jumping genes’: how polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming Arctic

‘Jumping genes’: how polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming ArcticUnder the radar The species is adapting to warmer temperatures

-

Environment breakthroughs of 2025

Environment breakthroughs of 2025In Depth Progress was made this year on carbon dioxide tracking, food waste upcycling, sodium batteries, microplastic monitoring and green concrete

-

Pros and cons of geothermal energy

Pros and cons of geothermal energyPros and Cons Renewable source is environmentally friendly but it is location-specific

-

How will climate change affect the UK?

How will climate change affect the UK?The Explainer Met Office projections show the UK getting substantially warmer and wetter – with more extreme weather events