A parent's guide to dropping your kid off at college

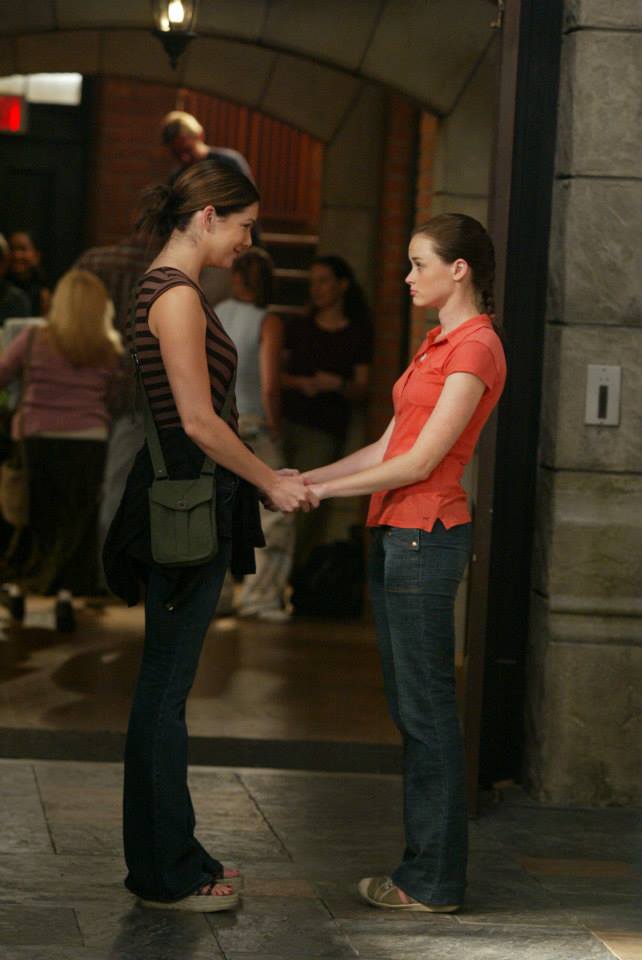

Your kid is going to college. You have to let him go. Here's how.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

My Facebook feed has been feeding me some rather over-the-top updates lately.

Escorting little Brant off to Vassar! How the time flies!

Family road trip — Ohio State, here we come!

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

I think the most cringe-worthy may have been the proud parents who emblazoned the side of a U-Haul (and a few personalized T-shirts) as they proudly paraded their 18-year-old daughter and her stuff through downtown Los Angeles.

Madison's USC Move-in Company!

As recently as 20 years ago, most parents would have dropped their newly minted freshman off at the curb outside the dorm and waved "goodbye." (My parents gave me a hug and a bus ticket.) Today's parents, however, seem compelled to immerse themselves in the whole new-to-college experience, even down to stage-managing their kid's move-in and class registration down to the last detail.

I asked Julie Lythcott-Haims, former dean of freshmen at Stanford University and author of the breakout parenting tome How to Raise an Adult, to help me understand the dynamics behind this shift. Her answers are both fascinating and (I hope) instructive for both parents and their college-student kids. Below, a lightly edited Q&A.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Why are today's parents actually accompanying their kids to college and even taking part in orientation, etc.?

Over the past 30 years, due to fears over both safety and what it takes to succeed in our society, we've seen a steady encroachment of parents into domains previously inhabited by children — play, organized activities, homework, school. Parents who have sidled right alongside their kid through the challenges of middle and high school have a hard time pulling back when it's time for college. This is why, in the late '90s, we began seeing parents come to campus expecting to have a role to play in college life. From the outside it looks absurd when, say, a mom or dad asks questions about research opportunities or about how the course registration process works, but from that parent's vantage point, it's just a continuation of what they've always done to further their child's protection and success. The trouble is, if the child (now an adult) never does the question-asking (or problem solving, or choice-making, or investigating) for him or herself, he or she never learns. That child becomes a chronological adult who's rather incapable of handling things on his or her own.

To what extent are the schools themselves to blame? Early parent engagement can mean greater fundraising potential in the future. How much of "Family Freshman Week" is driven by Development as opposed to Dean of Students' offices?

I don't think the Development Office takes much of an interest in "Family Freshman Week." No. Schools themselves are not to blame. Schools are interested first and foremost in the intellectual and personal development of 18- to 22-year-old adults. Schools are only embracing parents nowadays because parents expect to be involved, not the other way around. How do I know? Because I worked through the years of transition from "Why are these parents so involved in the lives of their college kids?" to "Okay. Parents are hyper-involved no matter what we say, so how can we make this work."

Do most 17- to 19-year-olds need or want their parents to accompany them to college, set up dorm rooms, and attend opening-of-school activities? If not, what holds the young adults back from expressing their preferences to the older ones?

I wrote my book because college kids weren't mortified by their parents' constant involvement in every aspect of their lives. I wrote my book because they welcomed it. Millennials have grown accustomed to a very well-meaning, better-educated, more-influential person or two doing the thinking, planning, decision-making, and problem solving for them; that's what keeps them from asking their parents to back off. In short, they like it. And let's face it, there's often a short-term gain when your parent sets up your room for you, contests a grade for you, or talks to your roommate's parent about a problem you and your roommate are having. But the long-term cost is terribly detrimental. If you haven't done for yourself, you can't do for yourself. What's to become of that individual — let alone a society populated by such "adults?"

Of course every family is different, but what sort of general advice would you offer parents as they approach that ultimate "Off to School" moment?

Love is good. Support is good. Infantalization of 18-year-olds is not good. In fact, it causes them psychological harm. Too many parents today seem to fear — or outright believe — that their son or daughter is somehow less capable of navigating a college experience that was routine for 18- to 22-year-old students not that long ago. Has college gotten harder to navigate? No. What's changed is this: Parents are accustomed to being/doing/thinking for their kids in the K-12 environment, so they can hardly stop when the stakes are higher.

Here's another way to think about it: Some 18-year-olds go off to the military. Others go off to the world of work. Others go to college. If you're the parent of someone going to college, ask yourself how you'd be behaving if your kid was headed to the Army or the workplace. Why does a young person who's going to college — a place with a lot of structure and support systems — need more support than those other kids? Look, I'm not a curmudgeon. Come to campus, drop your kid off, make the bed, set up the curtains, use your drill to loft a bed or reorganize a wardrobe, attend a financial aid session, a campus safety session, and a workshop on letting go. Then go home. It's college now. Their college experience, not yours. Trust that they'll be fine. Want for them to be fine. Want for them to be more than fine. Want for them to be able to function as the capable, successful adult you've always dreamt they would be.

Practically speaking, have a conversation with them before they leave for college. Say, "You're an adult now, and we trust you to be able to make good decisions and be in charge of your own life." Form a communication plan for how often you'll talk/text now that they're in college, and tell them you'll let them take the lead on initiating those communications. Then sit on your hands for three weeks if it takes them that long to connect with you. As one parent just relayed to me, she had to do exactly that a year ago with her college freshman son. They're not dead. They're in college. Navigating a complex new system, making new friends, learning at a whole new level. It's what you've always wanted for them.

Now let them go and experience that for themselves.

Leslie Turnbull is a Harvard-educated anthropologist with over 20 years' experience as a development officer and consultant. She cares for three children, two dogs, and one husband. When not sticking her nose into other peoples' business, she enjoys surfing, cooking, and writing (often bad) poetry.

-

The environmental cost of GLP-1s

The environmental cost of GLP-1sThe explainer Producing the drugs is a dirty process

-

Greenland’s capital becomes ground zero for the country’s diplomatic straits

Greenland’s capital becomes ground zero for the country’s diplomatic straitsIN THE SPOTLIGHT A flurry of new consular activity in Nuuk shows how important Greenland has become to Europeans’ anxiety about American imperialism

-

‘This is something that happens all too often’

‘This is something that happens all too often’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day