America's foreign policy God complex

The U.S. is more powerful than any other single nation on the planet, but it is not unlimited in what it can accomplish or control. Not even close.

As dawn broke over the Middle East on Tuesday morning, no one thought the day would end with NATO working to avert an escalation of armed conflict between Russia and one of the alliance's members (Turkey). But that's the unpredictable way that events sometimes unfold in international affairs, especially when several world and regional powers with divergent interests are involved in a multi-front war.

These dangerous tensions serve as a perfect backdrop for reading and pondering two important documents: a speech that Hillary Clinton delivered last week at the Council on Foreign Relations, and an essay by Robert Kagan, the smartest of the neocons (and sometime Clinton advisor), in Saturday's Wall Street Journal.

Unlike so many of the blustering Know Nothings trying to become the Republican nominee for president, Clinton and Kagan know a tremendous amount about the world. Clinton, in particular, sounds comfortable talking in granular detail about the intricacies of international affairs, and her confident grasp of the complexities of the Greater Middle East far outstrips what any of the GOP candidates are capable of.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Yet Clinton's speech and Kagan's essay manage to inspire very little confidence. Both are deeply mired in a delusion that began to spread through the American foreign policy establishment at the end of the Cold War and has risen to complete dominance since 9/11. This is the delusion that the United States can and should act as the world's "indispensable nation," leading not just the "free world" but the entire world, using "smart power" to get numerous powerful, independent nations to do exactly what we think must be done to enforce global order as we conceive it.

The really astonishing thing about this delusion is its persistence — its capacity to withstand abundant evidence that it is wildly unrealistic. Even after the messy conclusion of the Gulf War. And the endlessly forestalled and ultimately indecisive outcome in Afghanistan. And the long, hard, bloody slog in Iraq. And the mess of the Arab Spring. And the anarchy in Libya. And the rise of ISIS from the chaos of the Syrian civil war.

Even after all of that, the most intelligent and accomplished candidate for president and the most thoughtful neoconservative analyst continue to believe it's possible for the United States to treat the world as its personal plaything.

If this isn't a God complex, then I don't know what is.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Clinton's speech is very clear about what the Democratic presidential frontrunner thinks needs to happen in the Middle East. She wants Assad removed from power in Syria; Russia no longer bombing Syrian rebels; Turkey no longer bombing the Kurds and instead helping us in the fight against ISIS; Iraq's army capable of and willing to take the lead in retaking territory from ISIS; the region's Sunnis undergoing a second "awakening" in which they persuade ISIS fighters to abandon the apocalyptic Islamist movement; Saudi Arabia cutting off its support to jihadists; and Iran no longer provoking Iraqi and Syrian Sunnis to withdraw from the political process in their countries.

It sounds great!

Except that there's only a small chance of accomplishing one or two of these items, and zero chance of accomplishing them all.

How do we know this? Because there's one crucially important piece missing from Clinton's analysis: a discussion of the cacophony of clashing interests at play in the region. Clinton simply lists off the various state and sub-state actors involved, explains what we need them to be doing to advance our vision of order, and asserts that she will make that happen.

I'm sorry, but neither she nor the United States is nearly charming enough to pull that off.

To focus on just one of the players: Vladimir Putin wants to keep Syria's Assad in power, in part to protect Russia's naval and air bases in the region, and he's backing it up with the Russian air force. The only way to persuade him to stand down from this position would be to offer him something in return — the lifting of sanctions tied to Russia's annexation of the Crimea, for example. Is Clinton willing to make him an offer like that? I doubt it. But then what? She doesn't say, and it's hard to see what it might be.

And what about Syria itself? Let's imagine that the Obama administration or a future Clinton administration manages to orchestrate Assad's departure. What then? Do we have any reason to believe that the resulting power vacuum would be filled by factions both moderate enough to support the formation of a decent (let alone democratic) government and strong enough to prevail against others factions that would oppose it using violence?

The answer should be obvious.

And that's just Russia and Syria. Once you begin to contemplate the competing interests of the Islamic State, the Turks, the Kurds, the Iraqi Sunnis, the Saudis, and the Iranians and their proxies in Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon, it becomes apparent that Clinton's confident talk is really nothing more than that.

The same critique can be levied against Kagan, though with one important difference. Whereas Clinton is running for president and is thus terrified of endorsing what would be a very unpopular proposal to deploy American ground forces to fight ISIS, Kagan is quite comfortable suggesting that the U.S. will need 50,000 or so pairs of boots back on the ground in Mesopotamia.

That has the advantage of relieving the United States of the need to rely on the (most likely non-existent) goodwill of other actors in the region. (Who will fill the power vacuum in Syria? Why a few brigades of American soldiers, that's who!) But that doesn't mean it's a good idea.

Once again, the incapacity to learn from experience boggles the mind. When the U.S. attempted to occupy Iraq with a "light footprint" from 2003 through 2006, the result was a bloody insurgency that empowered al Qaeda and gave birth to ISIS. Only after George W. Bush's belated troop "surge," and the mass bribery of Sunni tribal warlords that we like to call the "Anbar Awakening," was some modicum of order (temporarily) restored.

Why should we assume that sending a modest number of American troops to occupy swaths of Syria and Iraq will work out so much better this time round? Kagan doesn't say. He just has faith that this time it will go much more swimmingly.

Events in the Middle East over the past two-and-a-half decades have been driven by many things, but one of them is the fervent anti-Americanism that's inflamed by our continual heavy-handed military meddling in the region. It was the presence of American troops in Saudi Arabia that inspired Osama bin Laden to found al Qaeda, just as it was our occupation of Iraq that catalyzed the insurgency that gave birth to ISIS. Sending tens of thousands of American troops back into the region is exceedingly unlikely to be better received this time around. We should instead expect it to inspire many thousands more to join the battle against the imperialist aggressor on ISIS's side.

Only someone incapable of learning from recent history and unwaveringly convinced of the omnipotence, omnicompetence, and omnibenevolence of the United States could believe otherwise. (For an even more cartoonish version of Kagan's metaphysical optimism, see John Bolton's suggestion that American troops help to birth a brand new nation — Sunni-stan — in western Iraq and northeastern Syria. Because, I guess, our great success at nation-building in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya shows that we're now up to the task of nation-creating.)

During the decades of America's bilateral conflict with the Soviet Union, the world might have resembled a chess board with the two superpowers squared off against each other and using the other nations as game pieces. But the absence of our one-time rival doesn't mean we now control every move on all sides of the board. It means the metaphor no longer holds.

The United States is more powerful than any other single nation on the planet, but it is not unlimited in what it can accomplish or control. Not even close.

The sooner our presidential candidates and their advisors learn to absorb this sobering fact and begin formulating policy on its basis, the better.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

5 hilariously slippery cartoons about Trump’s grab for Venezuelan oil

5 hilariously slippery cartoons about Trump’s grab for Venezuelan oilCartoons Artists take on a big threat, the FIFA Peace Prize, and more

-

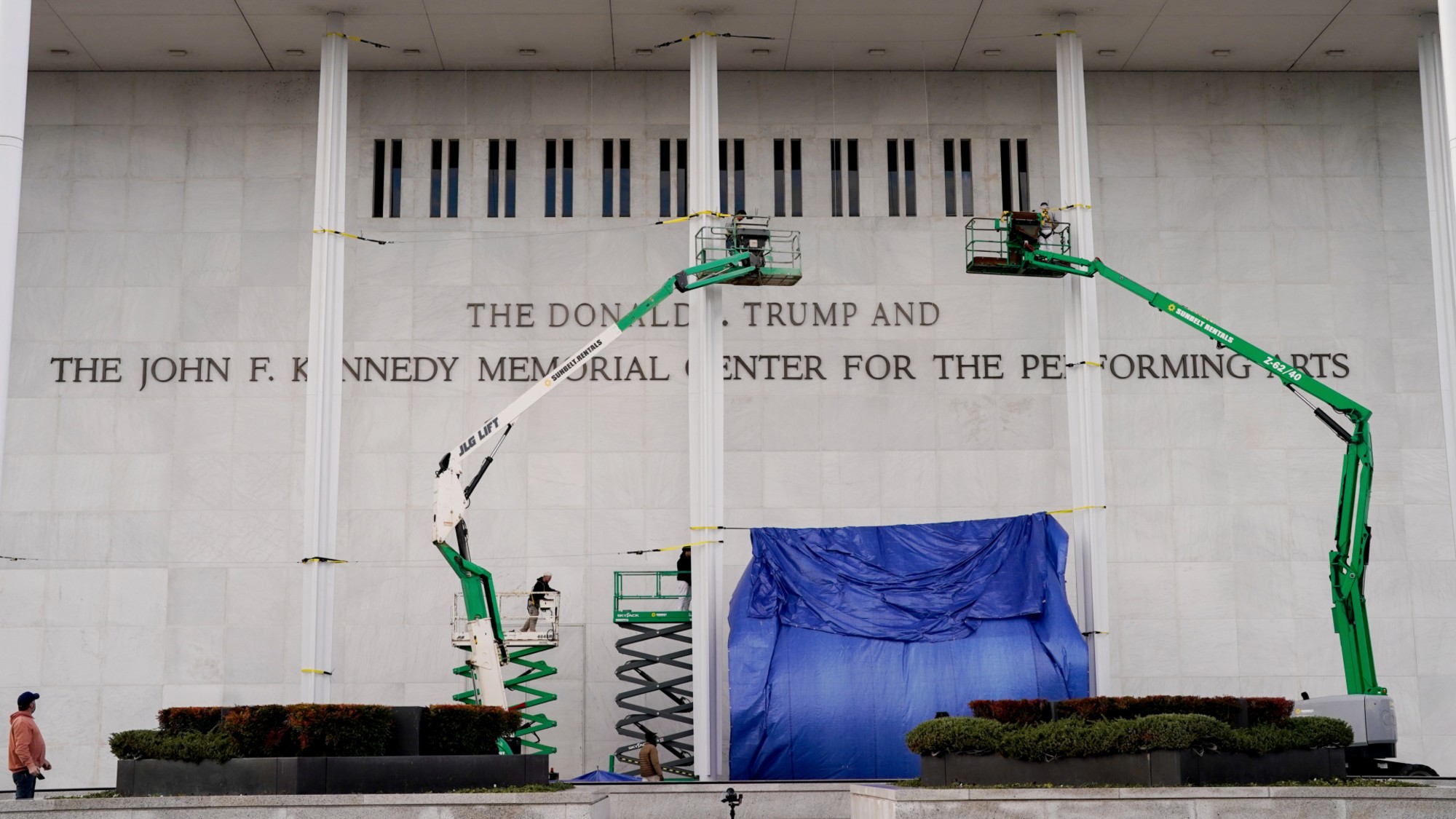

A running list of everything Trump has named or renamed after himself

A running list of everything Trump has named or renamed after himselfIn Depth The Kennedy Center is the latest thing to be slapped with Trump’s name

-

Do oil companies really want to invest in Venezuela?

Do oil companies really want to invest in Venezuela?Today’s Big Question Trump claims control over crude reserves, but challenges loom