The future of the religious right? Cruz and Rubio have very different ideas

Beneath Trump mania, Cruz and Rubio are fighting about the role faith should play in American politics

Roiling beneath the surface of the Trump mania in South Carolina is a battle between Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio over the future of the evangelical alliance with the Republican Party.

While Trump is drawing the support of about a third of white evangelicals here, the attraction is probably more about Trump's star power and pledges of greatness. Trump's dominance in the race is muddying developing fault lines within evangelical culture. These divides are prompting shifts in the way some evangelicals are choosing to engage in politics. A splinter group, mostly in the Rubio camp, is seeking to build a new kind of religious right with a less combative public face.

These schisms are likely to continue to play out in Republican politics, even if this cycle's peculiarities have temporarily obscured them.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

South Carolina is notorious for splitting its significant evangelical vote in the Republican primary. In 2008, that split benefited the least evangelical candidate, John McCain. In 2012, when white evangelicals made up 65 percent of the Republican electorate, Newt Gingrich won the primary with 44 percent of the evangelical vote, and Mitt Romney and Rick Santorum were behind with an even split — 22 and 21 percent, respectively.

In the most recent South Carolina poll from Monmouth University ahead of Saturday's primary, Trump is leading the field in white evangelical support with 33 percent. Cruz (21 percent) and Rubio (18 percent) are splitting 39 percent of the white evangelical vote. Jeb Bush, Ben Carson, and John Kasich are evenly splitting the remaining 24 percent.

Both the Cruz and Rubio camps recognize the need to target white evangelical voters here and across the country. Although the religious right's obituary is frequently written and is just as frequently wrong, white evangelicals still make up about 50 percent of Republicans in South Carolina, and more than a third of Republicans nationwide. For the party, ceding the evangelical vote to Trump would mean failing to continue to build this key coalition — or, more aptly, reconciling the factions that have emerged.

What's more, as an overall share of South Carolinians, white evangelicals (26 percent) are losing ground to non-white Christians (29 percent), according to the Public Religion Research Institute, so it's important for white evangelicals to consolidate and build on what they've got. Although non-white Christians are a small segment of Republicans in the state (10 percent), both Rubio and the state's governor, Nikki Haley, who endorsed him on Wednesday, emphasized their backgrounds as the children of immigrants. Yet Rubio seemed to tiptoe around the politics of immigration, a sign of how Trump has made it red hot.

Cruz is old-school religious right; he presents himself as a savior figure who will "unleash the holy wrath of the United States" on "radical Islamic terrorists." By contrast, when endorsing Rubio, Haley used words like "grace," "compassion," and "humble."

The Cruz camp is heavily dominionist. He has amassed a lengthy roster of evangelical endorsers, who believe that conservative, "bible-believing" Christians need to take political power to trigger a religious revival the country needs.

Cruz's high-profile religious endorsers include prominent figures in the culture wars, such as Focus on the Family founder James Dobson. Dobson appears in a new campaign ad for Cruz, recorded after the death of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, vouching for the senator's willingness to nominate genuinely conservative justices. The South Carolina evangelical chairman for Cruz's campaign, Pastor Mike Gonzalez, calls the separation of church and state a "myth." Television and radio personality Glenn Beck, who campaigned here this week with Cruz, said on his radio program that with Scalia's death, God "woke the American people up" to the need for a "constitutionalist" like Cruz for president.

Rubio, on the other hand, is drawing support from evangelicals who say they don't want a "pastor-in-chief." While it's important to them that the president be a pious Christian opposed to abortion, same-sex marriage, and Planned Parenthood funding, they don't see politics as the means to religious redemption. They tend to use phrases like "human flourishing" when talking about domestic policy — referring to what they perceive to be the impact of lower taxes and less regulation on the economy.

Rubio relies less on evangelical endorsements and instead has created "advisory boards" on issues like "religious liberty" and "marriage and family." The campaign describes the Marriage and Family Advisory Board as comprised of people (mostly academics and think tank fellows) who "have devoted themselves to rebuilding a vibrant culture of marriage and family."

Cruz wants to keep fighting the culture wars like it's, well, 1999. For Rubio's evangelical supporters, Christian values are eternal, but it's time for new battle tactics.

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Sarah Posner writes about religion and politics. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, and many other publications.

-

'Horror stories of women having to carry nonviable fetuses'

'Horror stories of women having to carry nonviable fetuses'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By Harold Maass, The Week US Published

-

Haiti interim council, prime minister sworn in

Haiti interim council, prime minister sworn inSpeed Read Prime Minister Ariel Henry resigns amid surging gang violence

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

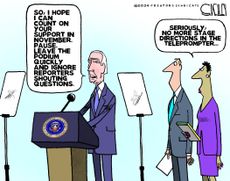

Today's political cartoons - April 26, 2024

Today's political cartoons - April 26, 2024Cartoons Friday's cartoons - teleprompter troubles, presidential immunity, and more

By The Week US Published

-

Arizona court reinstates 1864 abortion ban

Arizona court reinstates 1864 abortion banSpeed Read The law makes all abortions illegal in the state except to save the mother's life

By Rafi Schwartz, The Week US Published

-

Trump, billions richer, is selling Bibles

Trump, billions richer, is selling BiblesSpeed Read The former president is hawking a $60 "God Bless the USA Bible"

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

The debate about Biden's age and mental fitness

The debate about Biden's age and mental fitnessIn Depth Some critics argue Biden is too old to run again. Does the argument have merit?

By Grayson Quay Published

-

How would a second Trump presidency affect Britain?

How would a second Trump presidency affect Britain?Today's Big Question Re-election of Republican frontrunner could threaten UK security, warns former head of secret service

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

'Rwanda plan is less a deterrent and more a bluff'

'Rwanda plan is less a deterrent and more a bluff'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By The Week UK Published

-

Henry Kissinger dies aged 100: a complicated legacy?

Henry Kissinger dies aged 100: a complicated legacy?Talking Point Top US diplomat and Nobel Peace Prize winner remembered as both foreign policy genius and war criminal

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Last updated

-

Trump’s rhetoric: a shift to 'straight-up Nazi talk'

Trump’s rhetoric: a shift to 'straight-up Nazi talk'Why everyone's talking about Would-be president's sinister language is backed by an incendiary policy agenda, say commentators

By The Week UK Published

-

More covfefe: is the world ready for a second Donald Trump presidency?

More covfefe: is the world ready for a second Donald Trump presidency?Today's Big Question Republican's re-election would be a 'nightmare' scenario for Europe, Ukraine and the West

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK Published