A capitalist critique of consumerism

If humanity collectively decided to stop buying pointless junk, the economy wouldn't grind to a halt. Far from it.

It's become a cliché to note that we in the modern world have gorged on an unprecedented abundance of stuff. Still, Frank Trentmann's new book on consumerism, The Empire of Things, begins with an eye-opening fact: "A typical German owns 10,000 objects." Let that sink in. Ten thousand!

The second and third sentences are hardly less forgiving. "In Los Angeles, a middle-class garage no longer houses a car but several hundred boxes of stuff. The United Kingdom in 2013 was home to six billion items of clothing, roughly 100 per adult; a quarter of these never leave the wardrobe." Though consumerism is often seen as a liberal bogeyman, even supporters of free enterprise — of whom I am one — need to admit we have a problem.

Let's start, however, by noting that consumerism's defenders have more than half a point.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

That's because the alternative to "consumerism" is, literally, the Soviet Union. Back in the USSR, you had one brand of car, and it was certainly no-frills. So were clothes, housing, books, entertainment, and everything else. Anyone who cares about human flourishing should remember the well-attested-to scenes of East Germans coming to West Germany after the Berlin Wall fell and literally falling down crying the first time they walked into a supermarket. What looks like shallow consumerism to us is also the only alternative to deep, grinding misery.

Another important point is that one person's consumerism is another person's welfare-enhancing piece of humanity. When Facebook games like FarmVille (remember that?) were all the rage, our great and good mercilessly mocked anyone who would invest so much time and energy into virtual farms, and decried the companies that made those games as nothing but giant wastes of energy and capital. But I guarantee you there's more than one frazzled housewife or single mom in Ohio with three kids for whom that virtual farm is the only oasis of peace and tranquility in her life. And who am I to say that her hobby is "consumerism" and my hobby is a welfare-enhancing hobby?

Or, to take another example, it's an understatement to say that the world of fashion is stunningly superficial. But fashion is also a way to express oneself and to construct a social identity, which is a worthy part of life. And remember: The alternative is Mao collars for everyone. And who will sit on the omniscient and benevolent committee that decides what counts as shallow consumerism?

Another place where the consumerists have a point is the upside of ads. Yes, ads bludgeon every sphere of our existence, but as Amar Bhidé, one of the greatest and most underrated business scholars out there, argues in his book The Venturesome Economy, what we think of the "shallow" side of the consumer economy is actually key to innovation.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

We think of inventions as coming fully-formed from the head of geniuses — Thomas Edison with the light bulb, Steve Jobs with the iPhone — but the reality is much more complex. The first version of an innovation is rarely any good, but it blossoms into a game-changer because "venturesome consumers" are willing to take a chance on something wonky, which encourages innovators to build second, third, and fourth versions. Perhaps as much as its accumulation of capital or its regulatory environment, America's infamous and much-decried consumerism is a key element of its vaunted innovation engine.

But here is where I part ways with the consumerists and explain why I think you should only give two cheers to consumerism.

We're sometimes told that consumerism is what creates jobs and livelihoods. If we didn't buy meaningless trinkets, what would all the people who have jobs building and selling them do? This sort of reasoning exposes the fundamental clash in worldviews at the heart of most visions of economic life. I call them the "productivist view" and the "creative view."

What is an economy for?

The productivist view says that an economy is for producing stuff. Its endless cycle of buying and selling provides both jobs and the stuff we need. In this view, it doesn't matter if we buy iPhones or punch-button dumbphones — the former might be better, but so long as there are enough factories and offices humming to give everyone a job and the means to buy the necessities of life, it means the economy is going well.

The creative view says that an economy is what happens when people cooperate to solve problems. The cycle of buying and selling just happens to be the most productive process to enable that cooperation.

In this scheme, almost all progressives are productivists. But a lot of people who identify with the right, or who support capitalism, are also productivists.

The liberal economist John Maynard Keynes was a productivist. His most famous idea — which says recessions can be overcome by pumping more money into the economy to kick-start the buying-selling cycle — is classic productivism. But the right-wing alternative — the idea that cutting taxes also promotes more buying and selling — is also productivist.

My belief is that the productivists are right in the short term, because some form of stimulus really is a good idea during a recession. But in the long run, the productivists are wrong and the creativists are right. The reason why billions of people no longer even have a concept of the hardscrabble, food-insecure life their forebears led is not because people started buying and selling more, but because people invented technologies — engineering technologies, like the steam engine, and social technologies, like modern finance and the limited liability corporation — that enabled people to cooperate more to solve more problems.

And here's where the anti-consumerists have a point: If we all suddenly and collectively decided to stop buying pointless junk, the economy wouldn't grind to a halt forever. People would just start working on more interesting, more valuable things.

I can refrain from judging the Ohio mom who loves FarmVille, and the engineers and designers who make the game she loves. But I can also think that the world would be a better place if she took up woodworking instead and those engineers and designers made educational games.

So, what should we do? What regulation should be put in place? None. At the end of the day, the only "remedy" for "consumerism" is the self-knowledge to realize what truly contributes to our own flourishing and the virtue to carry it out. The alternative to consumerism isn't political. It is cultural and even — dare I say it — metaphysical.

But I do want my fellow capitalists to realize that if they take a shot at consumerism once in a while, they're not taking a shot at their own side. To the contrary, they're reminding us of the first principle of free enterprise — that what a flourishing economy needs is not piles of junk, but creativity.

Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry is a writer and fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. His writing has appeared at Forbes, The Atlantic, First Things, Commentary Magazine, The Daily Beast, The Federalist, Quartz, and other places. He lives in Paris with his beloved wife and daughter.

-

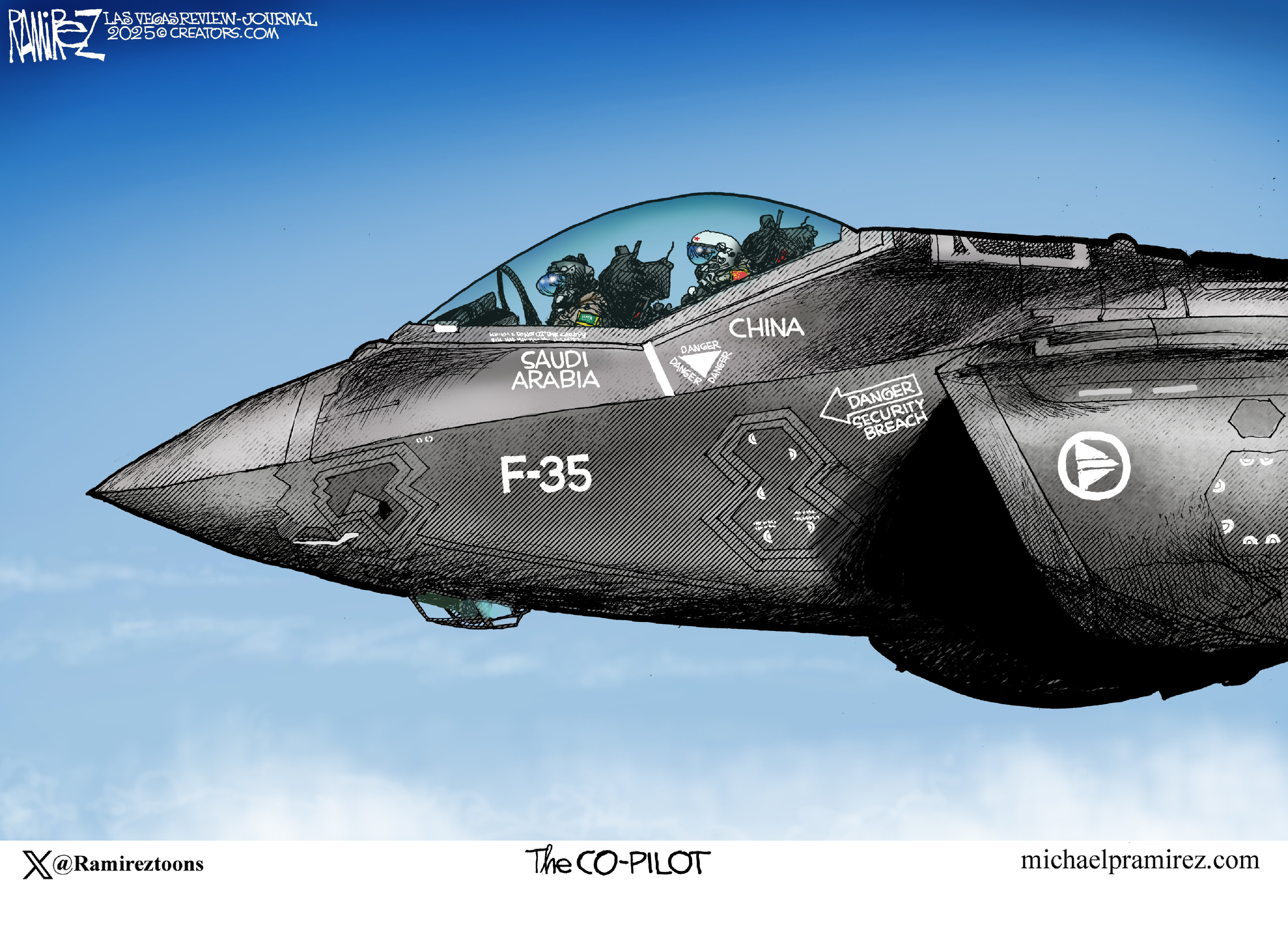

Political cartoons for November 30

Political cartoons for November 30Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include the Saudi-China relationship, MAGA spelled wrong, and more

-

Rothermere’s Telegraph takeover: ‘a right-leaning media powerhouse’

Rothermere’s Telegraph takeover: ‘a right-leaning media powerhouse’Talking Point Deal gives Daily Mail and General Trust more than 50% of circulation in the UK newspaper market

-

The US-Saudi relationship: too big to fail?

The US-Saudi relationship: too big to fail?Talking Point With the Saudis investing $1 trillion into the US, and Trump granting them ‘major non-Nato ally’ status, for now the two countries need each other