Bernie Sanders' critics now say he's a 'con man.' That reveals a lot — about them.

They don't know half as much about politics as they think they do

Kevin Drum of Mother Jones, like most baby boomers, is no fan of Bernie Sanders. With the primary all but settled in favor of his preferred candidate, he's chosen now as a time to outline why he never felt the Bern: Sanders is a con man!

It'd make a good #slatepitch. But on the merits, it mainly reveals the pinched and defensive worldview of '90's liberalism. Rather than being tricked, Sanders voters are simply taking part in the long tradition of populist politics.

The first item in Drum's anti-Bernie brief is that he isn't using "revolution" in its proper sense. While I'll cop to Sanders' campaign severely defining the term down compared to Lenin or George Washington, this is little more than pedantry. It turns out that political slogans are basically never constructed with the scrupulous historical care of a grad school seminar. This can be seen in the Sanders platform itself. Despite it being hugely more aggressive than his primary opponent, objectively speaking it's a modest expansion of welfare spending that would not even cover half the policy distance between the U.S. and Denmark. He is not proposing to seize the means of production.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

This brings me to the meat of Drum's case. His real problem with Sanders is that his ambitious ideas are teaching a generation to think that quick, sweeping change is possible, which is bad because the way politics works is Abandon Hope, All Ye You Enter Here:

[I]f you want to make a difference in this country, you need to be prepared for a very long, very frustrating slog. You have to buy off interest groups, compromise your ideals, and settle for half loaves — all the things that Bernie disdains as part of the corrupt mainstream establishment. In place of this he promises his followers we can get everything we want via a revolution that's never going to happen. And when that revolution inevitably fails, [do his] impressionable young followers...give up? I don't know, but my fear is [they will]. And that's a damn shame. They've been conned by a guy who should know better, the same way dieters get conned by late-night miracle diets. [Mother Jones]

Let's look past the deliberately offensive language here portraying Sanders' young voters as naive rubes. This model of how good policy is obtained — "work your fingers to the bone for 30 years and you might get one or two significant pieces of legislation passed," as Drum puts it — is simply not correct.

Let's review the history of ObamaCare. After a couple of previous failures, Hillary and Bill Clinton tried and failed to pass a universal health care plan in 1993. Democrats gave up for awhile after that. In 2000, Al Gore had a little plan for kids, but mainly ran on paying off the national debt and targeted tax cuts. In 2004 John Kerry had a slightly more ambitious plan, but it was largely lost in foreign policy discussion. But by 2006 the failure of the Iraq War was obvious, and President Bush's disastrous bungling of Hurricane Katrina delivered Democrats a landslide victory in that year's midterm elections.

In 2007 universal coverage got a fresh start with John Edwards' plan, followed quickly by Clinton's and Obama's. In 2008 Obama won a smashing victory in the general election, on the back of Bush's extreme unpopularity, the collapsing economy, and Obama's own deft campaign. Fast forward through the Al Franken recount, Edward Kennedy's unfortunate demise, and a lot of legislative shenanigans, and ObamaCare was passed in March 2010.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Democrats as a party were not "working their fingers to the bone" trying to get universal health care through this entire time. For two whole presidential elections the party's nominees ran on measly little half-measures they barely mentioned. Instead, Democratic elites were doing the two-party system dance, trying like mad to win the next election but deciding what to do with a victory based on some complex mixture of demands from voters, demands from donors, perceived political risk, the general ideological climate, the latest groupthink from the pundit class, their own moral and political views, and so on.

ObamaCare — a basically mediocre program that is still a big improvement on the status quo — reflects its political origins. It's what milquetoast liberals had settled on as a reasonable compromise, so when George Bush handed them a great big majority on a silver platter, that's what we got. It was Bush's failed presidency, not 30 years of preemptively selling out to the medical industry, that got the job done.

Some version of this process is the way basically all good policy gets through, as Matt Karp argues. The left half of the political spectrum decides on a compelling set of ideas, and through a combination of luck (read: conservative failure), strategy, and popular mobilization, wins a brief mobilized majority that passes lots of good stuff very fast.

Stripped to its essentials, Sanders' campaign is following the political tradition of FDR and Lyndon Johnson: trying to convince people of the merits of left-wing policy and demanding candidates who champion that vision. He's trying to ensure that the next Democratic majority will aim much higher than ObamaCare. And as Greg Sargent points out, young voters have in fact shifted several points in a pro-government direction just in the past year or so.

Though I can't speak for everyone, I'd wager that young people are attracted to those ideas because they know what it's like to graduate with a crushing load of student debt or to have a baby in a country with no paid leave but which also expects both parents to work full-time. Or maybe they can just feel that the bottom half of the income ladder is getting a raw deal. They're not idiots in thrall to a political charlatan.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

‘If regulators nix the rail merger, supply chain inefficiency will persist’

‘If regulators nix the rail merger, supply chain inefficiency will persist’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

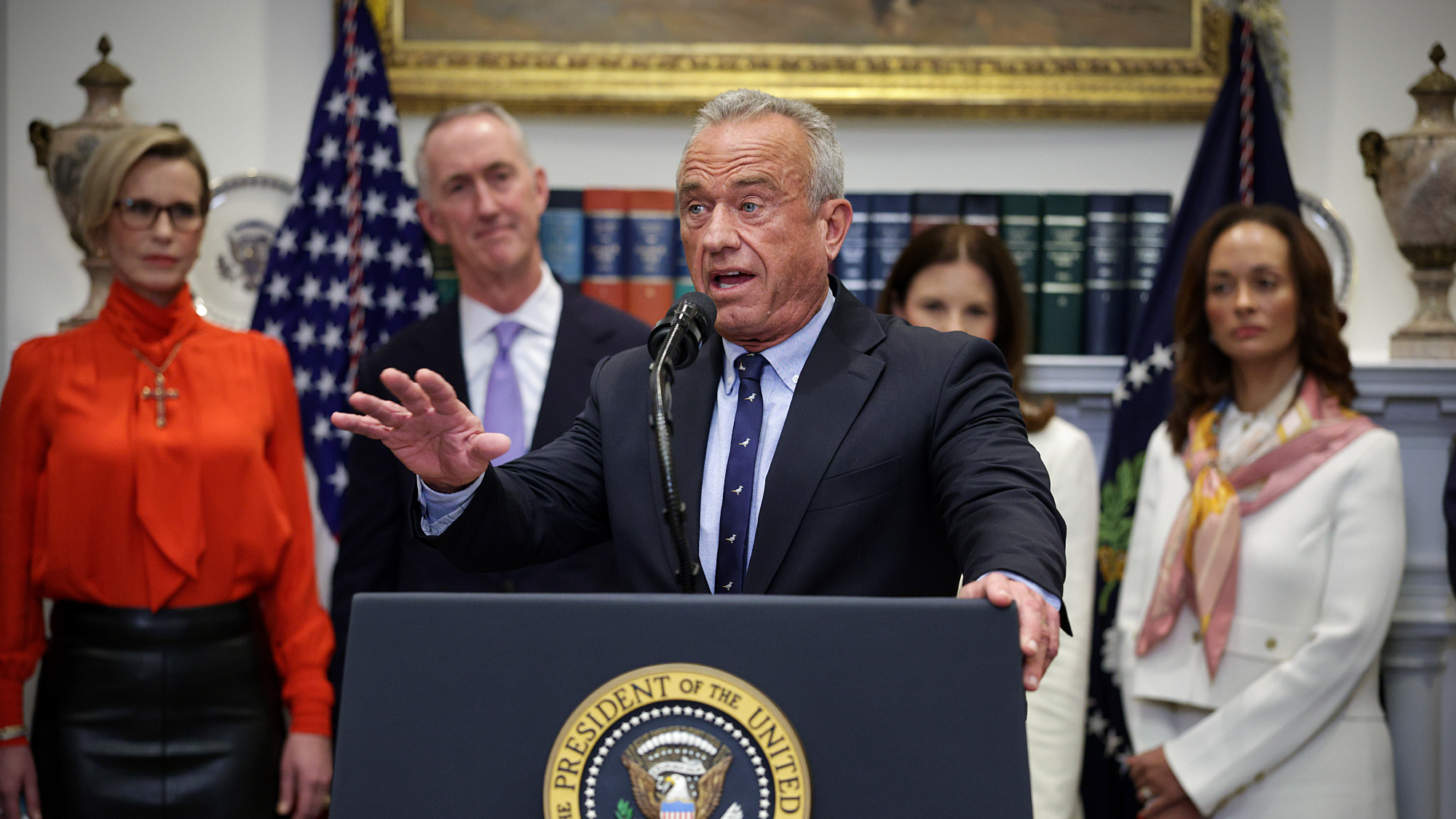

Trump HHS slashes advised child vaccinations

Trump HHS slashes advised child vaccinationsSpeed Read In a widely condemned move, the CDC will now recommend that children get vaccinated against 11 communicable diseases, not 17

-

Hegseth moves to demote Sen. Kelly over video

Hegseth moves to demote Sen. Kelly over videospeed read Retired Navy fighter pilot Mark Kelly appeared in a video reminding military service members that they can ‘refuse illegal orders’

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook