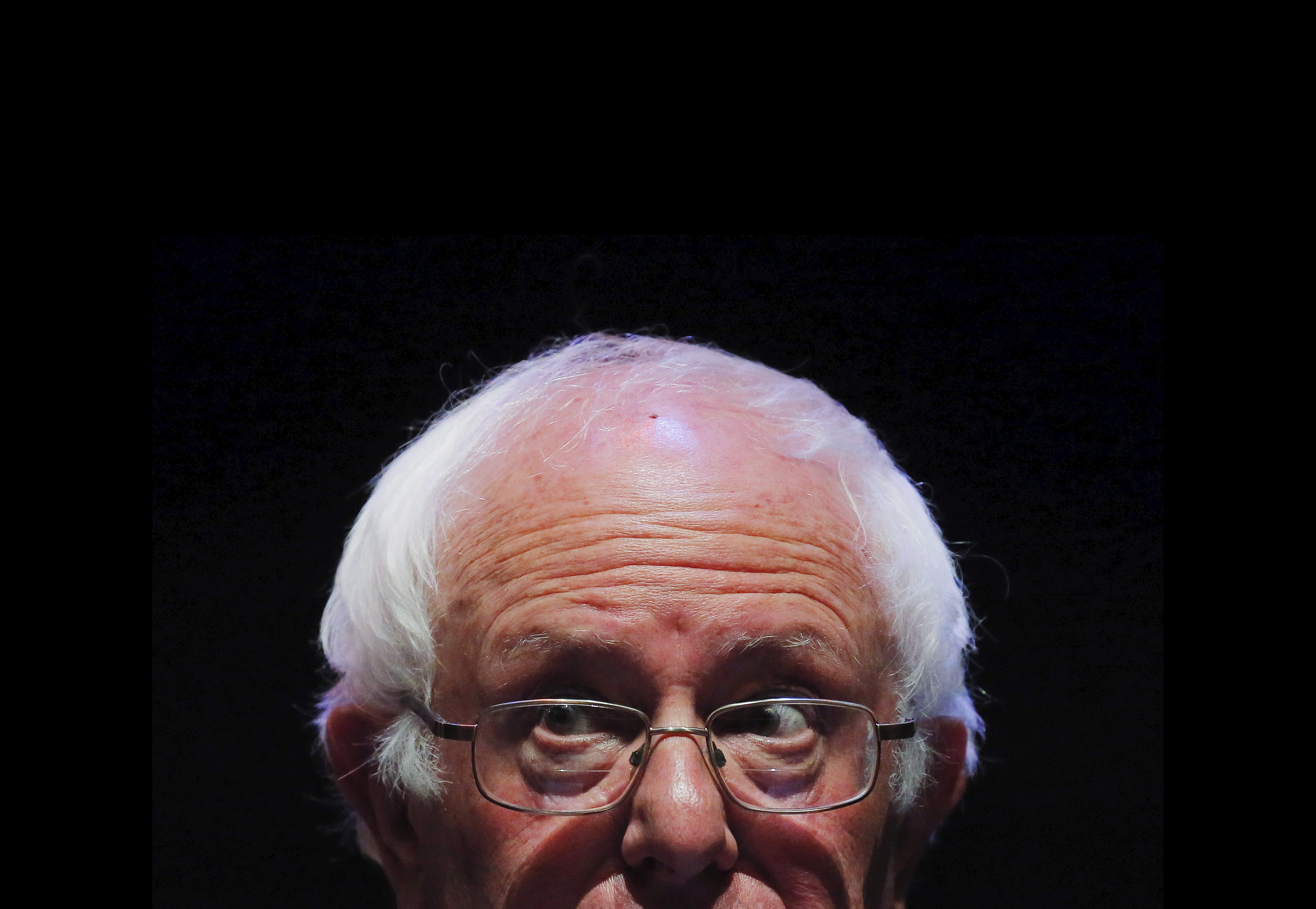

Bernie Sanders wants to make the Democratic Party more democratic — or does he?

Why Sanders' fixes to the primary system aren't nearly as democratic as they sound

What is Bernie Sanders up to? Even fervent Sanders fans realize that an election with Donald Trump on the ballot is coming up, but Sanders himself still has some demands he'd like to make of the Democratic Party. Some of these are about policy, but others are about process — how the Democrats will choose their presidential nominee in the future. The simple way to look at it is that the scrappy outsider candidate would like to make the system more open and democratic, so that scrappy outsider candidates might have a better shot next time around. But some of what Sanders suggests may not be quite as democratic as it looks.

The two main components of Sanders' proposal are to eliminate superdelegates, those high-falutin' party insiders who horde power for themselves at the expense of the people, and to make more (or all) of the primaries "open," meaning that you wouldn't have to be a Democrat to vote in them. About half the states have open primaries, and Sanders did slightly better in those than in closed primaries, but not enough that if all the primaries had been open he would have won the nomination.

But regardless of who gets a boost (ordinarily one would expect more moderate candidates to benefit from an open primary), it's far from clear that an open primary is inherently more democratic than a closed one. After all, the purpose of primaries is for each party to choose its nominee. It's perfectly reasonable for a party to say that it wants its voters, and only its voters, to make that choice. If a candidate can get the support of independents or crossover voters from the other party in a general election, that's something the party's own voters might take into consideration in making their selection. But it's still theirs to make.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

And if you understand the nature of the Democratic Party, you can understand why that idea might run into resistance from groups like the Congressional Black Caucus, which is vehemently opposing the idea of open primaries and of eliminating superdelegates.

Bernie Sanders struggled to win over African-American voters this year, which was a big part of the reason he came up short against Hillary Clinton. It wasn't surprising, given Clinton's longstanding ties with that community and its representatives, and the fact that as a Vermonter who had never been part of the Democratic Party until this year, Sanders had little experience and history with them. But even if you can't blame him for not doing better with them, it does mean that his candidacy didn't really represent the party he was trying to lead. African-Americans aren't some minor interest group; they're the Democratic Party's most important single constituency.

And the Democratic Party is nothing if not a coalition of constituencies: African-Americans, Latinos, union members, environmentalists, single women, urbanites, gay people, young people, and many other sometimes overlapping groups. Balancing all their interests and moving them in the same direction is what Democratic politicians have to do.

But don't forget that Bernie Sanders spent his entire career as an independent, becoming a Democrat only so he could run for president this year. So when he calls for getting rid of closed primaries, it can sound to many people in the party like he's trying to dilute their influence in favor of someone other than actual Democrats. That's the objection the Congressional Black Caucus raises, and they're also quick to point out that he hasn't called for the elimination of caucuses, perhaps because he did particularly well in them. But there are few things less democratic than a caucus. Because it requires extended time and can only be done in person, caucuses effectively disenfranchise whole groups of people who can't make it that evening — people who are homebound, shift workers, people who can't obtain child care, and many others. If Sanders called for their elimination, he'd have more credibility in making his case that he just wants to make the process more inclusive.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But surely he has a case to make on superdelegates, right? While there's something troubling about the possibility that they could hypothetically swing the convention, that doesn't mean that their presence denied Bernie Sanders the nomination, as much as he criticized them. Like every other election since they were devised, the superdelegates didn't determine anything in the end. Clinton won because she got more of the pledged delegates and more of the votes than Sanders. It wasn't any more complicated than that, and it wasn't "rigged."

You can certainly imagine a future election where there are two strong candidates and neither one has a clear majority, in which case the superdelegates would make the difference. But what are the chances they would overturn the will of their party's voters and rally behind the person who came in second? Pretty small. In 2008 many of them began on Clinton's side but moved to support Barack Obama when he pulled ahead. They would be terrified of the controversy that would erupt if they wielded their power to overrule what the foolish voters had done, even if they could.

If that's true, why bother having them at all? It's a perfectly good question, and it isn't easy to make an affirmative case for them. You could eliminate them without much cost. But that doesn't mean that they're preventing a truly democratic outcome.

Sanders supporters, however, look at those elected officials and seasoned party activists, and see exactly the "establishment" they want to fight against. There's another way to look at them, however. Those officials and activists are unquestionably the establishment, but they're also the people who sustain their party. They're the ones who go to all the boring meetings, who do the unglamorous local organizing, who invest huge portions of their lives in the task of keeping the Democratic Party an active and potent force in American politics. So you can understand if they don't react very well when Sanders and his supporters walk in and say, "Your party is completely corrupt and despicable. Now change it so instead of representing people like you, it represents people like us."

Even if they have a reasonable case to make, that's not going to be very persuasive.

Paul Waldman is a senior writer with The American Prospect magazine and a blogger for The Washington Post. His writing has appeared in dozens of newspapers, magazines, and web sites, and he is the author or co-author of four books on media and politics.

-

Political cartoons for February 1

Political cartoons for February 1Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include Tom Homan's offer, the Fox News filter, and more

-

Will SpaceX, OpenAI and Anthropic make 2026 the year of mega tech listings?

Will SpaceX, OpenAI and Anthropic make 2026 the year of mega tech listings?In Depth SpaceX float may come as soon as this year, and would be the largest IPO in history

-

Reforming the House of Lords

Reforming the House of LordsThe Explainer Keir Starmer’s government regards reform of the House of Lords as ‘long overdue and essential’

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred