How I learned to stop worrying and love germs

Be warned: This article is gross

The 17th-century Dutch scientist Antony van Leeuwenhoek loved looking through his microscope.

Leeuwenhoek first became known for his skill at making lenses — instruments that could magnify objects up to 270 times — and then for what he found when using one to examine a water sample from a nearby lake: thousands of little things dancing everywhere. (These things were actually single-celled protozoa.) Leeuwenhoek's curiosity soon led him to other close-up studies, and to discover even tinier creatures, like the bacteria living in rainwater. He was the first man to see microbes.

Soon enough, Leeuwenhoek began studying the plaque between his teeth. (Don't judge.) He reported: "All the people living in our United Netherlands are not as many as the living animals that I carry in my own mouth this very day."

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

This observation motivated him to seek out other mouths, including that of an old man who had supposedly never cleaned his teeth.

I know, gross. But take a deep breath. Keep going. Because Ed Yong's eye-opening I Contain Multitudes, out Aug. 9 from Ecco, offers reassurance that these living organisms are, more likely than not, your friends.

Yong's book is an admiring and thoroughly researched study of the microbial world: the "microscopic menagerie" of bacteria, fungi, archaea, and viruses that live, essentially, everywhere. Yong, however, focuses on their relationship with animals, and especially humans. Each of us is inhabited by a distinct set, or microbiome, whose denizens are influenced by the genes we inherit, the places we live, the people we encounter, the food we eat, and the drugs we've taken. The microbes in our bellies differ from the ones under our arms. The latest estimates suggest we each carry 39 trillion of them.

Yong argues that it's time to rethink microbes. They are not "neglected B-listers or sinister villains." They are complex, vital organisms. Yes, some are pathogens. But many serve as animals' invisible life partners, working to nurture, protect, and heal. (In humans, fewer than 100 species of bacteria cause infectious diseases; by contrast, the thousands of species in our guts are mostly harmless.)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Yong, an award-winning science writer who reports for The Atlantic, has amassed commanding knowledge of his subject. He opens with a history of microbial science before spending the majority of his time on more current research. Thanks to technological advances and a greater understanding of microbes' significance, work in the field has increased dramatically in the past few decades. Yong introduces readers to leading scientists, using their studies to illustrate the many functions that microbes perform.

Take Margaret McFall-Ngai, an expert on the partnership between the Hawaiian bobtail squid and V. fischeri. Her research has shown how the bacteria are essential helpers in forming the animal's light organs, which mimic moonlight to hide the squid's silhouette from nighttime predators. Without V. fischeri, the organs don't reach maturity.

Then there's Bruce German, who has dedicated himself to milk, which he hails as a "super food" — and human breast milk as a particularly exceptional variety. It turns out that milk nourishes not only babies but their resident bacteria as well — and that the latter are key to infants' developing an effective preliminary immune system.

The case for microbes' positive and necessary role in animals' lives is persuasive. In addition to guiding bodily development and helping calibrate immune systems, they aid in digestion, produce vitamins and minerals otherwise missing from diets, break down toxins, and perhaps even influence behavior. Not that he turns a blind eye to the darker side of microbial character. He spends time, for example, with Forest Rowher, a scientist studying the Pacific Ocean's fast-disappearing coral reefs. Their plight can at least partly be attributed to the coral's own microbes turning against them: The hungry organisms gobble up excess sugars and carbohydrates from the water, fueling a microbial bloom that in turn consumes surrounding oxygen and chokes coral.

The book also explores the debate around antibiotics and the pitfalls of our obsession with soaps, sanitizers, and all things "antibacterial"; how microbes pass between species and how they are inherited from one generation to the next; and how microbes may be manipulated for our benefit. Yong conjures a world where we dose our illnesses with capsules of microbes — this one to lower cholesterol, that one to reduce inflammation. In fact, some doctors are already harnessing their potential. Faecal microbiota transplants, where surgeons take stool from one donor and install it — along with its microbes — in the guts of another person, have successfully treated patients suffering from bacterial infections that cause relentless diarrhea. (Yong likens it to "an attempt to fix a faltering community by completely replacing it, like returfing a lawn that's overrun by dandelions.") Doctors have also reportedly used the procedure to treat irritable bowel syndrome, obesity, autoimmune diseases, mental health problems, and even autism.

The lexicon of bacteria becomes dizzying at times, but by and large Yong makes the science accessible to the layman. The book's most important through line, though, is the author's own microbial appreciation: His enthusiasm and wonder are propulsive. While Yong acknowledges that the questions outnumber the answers in this relatively nascent field, he thrills to the potential inherent in what scientists have already learned about microbes' astonishing powers. As a result, so do we.

Alexis Boncy is special projects editor for The Week and TheWeek.com. Previously she was the managing editor for the alumni magazine Columbia College Today. She has an M.F.A. from Columbia University's School of the Arts and a B.A. from the University of Virginia.

-

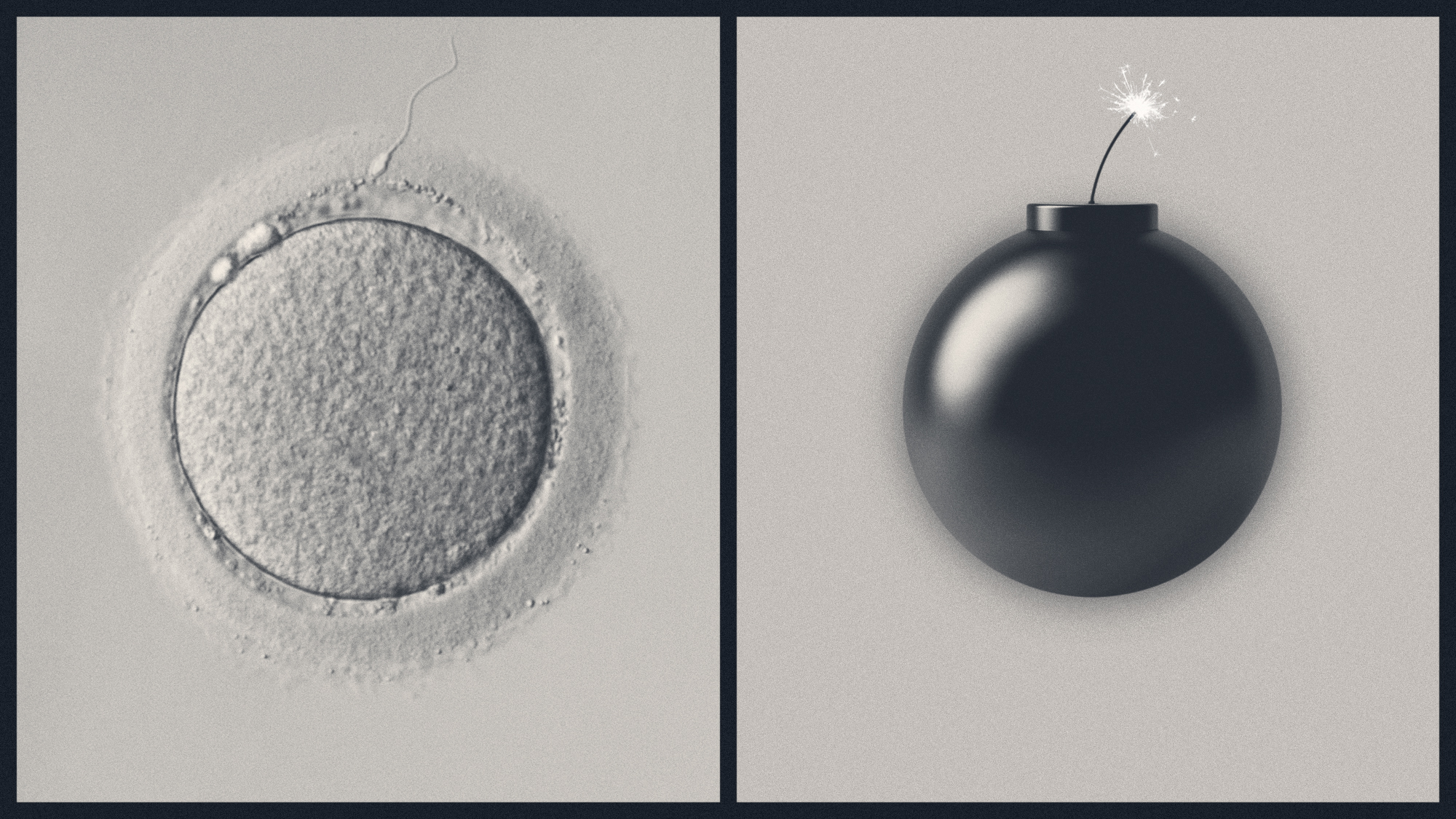

Does depopulation threaten humanity?

Does depopulation threaten humanity?Talking Points Falling birth rates could create a 'smaller, sadder, poorer future'

-

New White House guidance means federal employees could be hearing more religious talk at work

New White House guidance means federal employees could be hearing more religious talk at workThe Explainer Employees can now try to persuade co-workers of why their religion is 'correct'

-

Real-life couples creating real-deal sparks in the best movies to star IRL partners

Real-life couples creating real-deal sparks in the best movies to star IRL partnersThe Week Recommends The chemistry between off-screen items can work wonders