Why extreme weather is the new normal

Massive floods, prolonged heat waves, and destructive storms are becoming more common. Why?

Massive floods, prolonged heat waves, and destructive storms are becoming more common. Why? Here's everything you need to know:

How frequent are these events?

This year, the U.S. has had 12 billion-dollar disaster events — floods, wildfires, hurricanes, severe storms, and droughts that each caused more than $1 billion worth of damage. Adjusted for inflation, there were on average only about two such events a year in the 1980s, five a year in the 1990s and 2000s, and almost 11 a year between 2010 and 2015. The flooding in Louisiana in August was the country's eighth "once-in-every-500-years" weather event in a little over 12 months. Wildfires in California and other parts of the West grew at a rate of 90,000 acres a year between 1984 and 2011; in Alaska, four of the 10 worst fire seasons on record have occurred since 2004. The U.N. has calculated that the number of severe storms, floods, and heat waves worldwide is five times greater than it was in 1970; the World Bank estimates that extreme weather today affects 170 million people a year, up from 60 million three decades ago. "The weather has changed," says Myles Allen, head of the Climate Dynamics group at Oxford University. "'Normal weather,' unchanged over generations apart from random fluctuations, is a thing of the past."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Why is this happening?

Most atmospheric scientists say it's the result of climate change, which is now well underway: 2014 was the hottest year on record, but was surpassed by 2015; 2016 has been hotter still, with an average temperature about 2.25 degrees F above the late-19th-century average. While it's impossible to isolate and identify the cause of an individual storm or heat wave, the warming of the planet has almost certainly made extreme weather events much more likely. Warmer air absorbs more moisture: In wetter climates, that leads to bigger storms and floods; in drier areas, where there is little water to absorb, the higher temperatures exacerbate droughts. Mild winters produce less snowpack, leaving soil and forests parched and susceptible to wildfires in summer. Higher ocean temperatures provide more energy to hurricanes. An in-depth study of extreme weather by the insurance company Munich Re concluded that climate change is "the only plausible explanation for the rise in weather-related catastrophes."

Which areas are worst afflicted?

Different regions face different challenges: tropical storms in Florida and the rest of the Southeast; severe winters in the Northeast; tornadoes, floods, and hailstorms in the South and Midwest; droughts and wildfires in the West. It is the same around the world: Australia mostly struggles with heat waves of plus-100-degree temperatures and roaring wildfires; South America has been battered by severe storms; Europe has suffered from prolonged rainstorms that led to devastating floods. These weather events aren't just becoming more common; they're also becoming more powerful. The heaviest storms in the Southeast dump 27 percent more rain per event than they did in the 1950s. Hurricane Matthew, which caused widespread damage in the Carolinas in October, dumped a staggering 14 trillion gallons of water on the Southeast — 1 percent of the rainfall the entire country receives over the course of a whole year.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

How are people affected?

Lives are lost and a vast amount of property is destroyed. Extreme weather kills more than 500 Americans each year. The Louisiana floods, which saw 2 feet of rain fall in 48 hours in some areas, damaged 60,000 properties, costing an estimated $30 billion. Most Americans simply can't afford to rebuild after a natural disaster; the Federal Emergency Management Agency provides up to $30,000 to badly affected households, but that's not enough to fully repair the damage in many cases. In the rest of the world, extreme weather tends to cause less monetary damage but more fatalities. A 2003 heat wave in Europe, where air-conditioning is less commonplace, caused 70,000 premature deaths. Severe droughts can cause sharp rises in food prices; in undeveloped nations, flooding can spread disease and trigger epidemics.

Will it get worse?

Undoubtedly. How much worse depends on how much the world curbs carbon emissions. One study estimates that if greenhouse gas emissions continue unabated, areas of the Persian Gulf and Southeast Asia will experience heat waves with temperatures so extreme — in excess of 120 degrees F — that as little as six hours' exposure could be fatal. Another study concluded that by 2045, cities on the East and Gulf coasts will experience 10 times as many tidal floods, which will roll farther inland and last longer. The existing disaster plans of local, state, and federal governments are simply not designed for extreme weather events of this magnitude. "A lot of communities, a lot of cities, a lot of human settlements in general were designed to reflect the climate of the past," says Gavin Smith, director of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security's Coastal Resilience Center of Excellence. "We've designed cities to reflect a previous climate."

The price of poor forecasting

Weather forecasting is a notoriously inexact science — but the National Weather Service appears to be particularly bad at it. To make a forecast, meteorologists plug atmospheric data from weather stations and satellites into a weather model on a supercomputer, which then predicts how the conditions will change. The most accurate forecasters in Europe and in commercial companies run the model multiple times, with small tweaks to the variables — bumping up the temperature, for example. But the National Weather Service lacks the computing power to do multiple models. For budgetary reasons, the agency also gets very little data from TAMDAR, a highly accurate weather-monitoring system that uses sensors on commercial airliners. The effects of these limitations are clear. The National Hurricane Center initially predicted Superstorm Sandy would veer harmlessly offshore. In January 2015, the National Weather Service warned of a "crippling and historic blizzard" in New York; just 10 inches of snow fell, instead of more than 2 feet. With extreme weather events becoming more frequent, more and more lives depend on accurate forecasting. As Cliff Mass, a meteorologist who's a prominent critic of the National Weather Service, says, "An incremental improvement [in predictions] would make a huge difference."

-

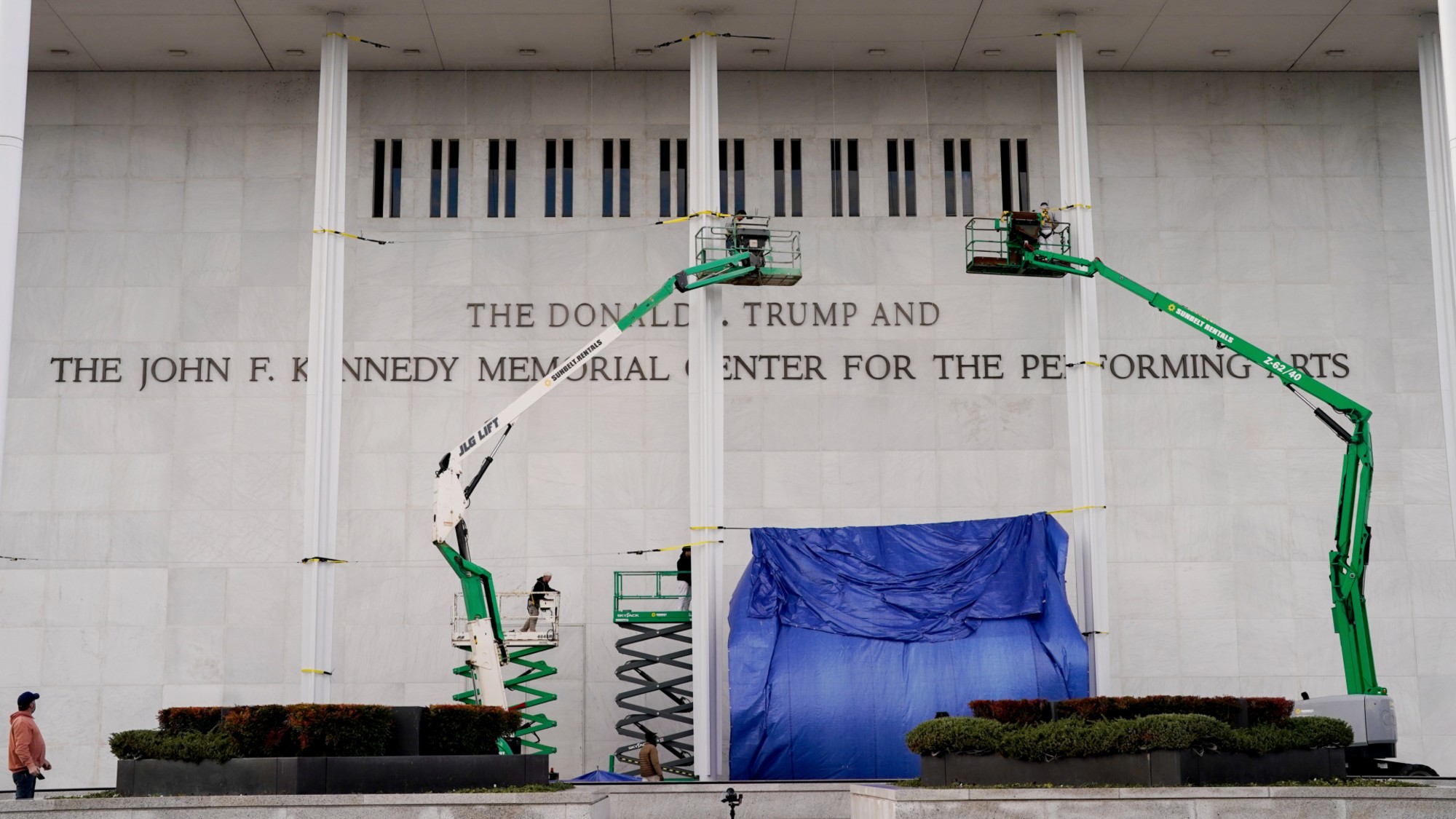

A running list of everything Trump has named or renamed after himself

A running list of everything Trump has named or renamed after himselfIn Depth The Kennedy Center is the latest thing to be slapped with Trump’s name

-

Do oil companies really want to invest in Venezuela?

Do oil companies really want to invest in Venezuela?Today’s Big Question Trump claims control over crude reserves, but challenges loom

-

‘Despite the social benefits of venting, people can easily overdo it’

‘Despite the social benefits of venting, people can easily overdo it’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Are zoos ethical?

Are zoos ethical?The Explainer Examining the pros and cons of supporting these controversial institutions

-

Will COVID-19 wind up saving lives?

Will COVID-19 wind up saving lives?The Explainer By spurring vaccine development, the pandemic is one crisis that hasn’t gone to waste

-

Coronavirus vaccine guide: Everything you need to know so far

Coronavirus vaccine guide: Everything you need to know so farThe Explainer Effectiveness, doses, variants, and methods — explained

-

The climate refugees are here. They're Americans.

The climate refugees are here. They're Americans.The Explainer Wildfires are forcing people from their homes in droves. Where will they go now?

-

Coronavirus' looming psychological crisis

Coronavirus' looming psychological crisisThe Explainer On the coming epidemic of despair

-

The growing crisis in cosmology

The growing crisis in cosmologyThe Explainer Unexplained discrepancies are appearing in measurements of how rapidly the universe is expanding

-

What if the car of the future isn't a car at all?

What if the car of the future isn't a car at all?The Explainer The many problems with GM's Cruise autonomous vehicle announcement

-

The threat of killer asteroids

The threat of killer asteroidsThe Explainer Everything you need to know about asteroids hitting Earth and wiping out humanity