End the war in Yemen, Mr. Trump

If the president-elect wants to bring some positive change to U.S. foreign policy, the war in Yemen would be the place to start

What will Donald Trump do with American foreign policy? It's impossible to know, especially in regards to the Middle East. He has articulated views that are war-weary and views that are hawkish. Many observers treat the Middle East as a zero-sum conflict between Shia and Sunni powers, in which the U.S. should mostly stick with its Sunni allies. But Trump has criticized America's Sunni ally Saudi Arabia as a costly dependent of the United States. At the same time he has also talked about ripping up President Obama's deal with Shia-dominated Iran.

But if Trump does want to bring some positive change to U.S. foreign policy, he should seek to end the war in Yemen.

Saudi Arabia announced on Monday that it would not extend a 48-hour cease-fire in its war there. The war doesn't make many headlines in the United States, even though the U.S. is directly involved in helping the Saudi military fire at targets in Yemen and blockade that country.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Here is the background. Yemen has been a divided country. The Houthis, a group of tribesmen from the north of the country who practice a variety of Shia Islam called Zaydi, had joined other groups in the Yemeni revolution of 2011. But they found themselves excluded from power again when the transitional government was formed. That government was weak and seen as a cat's paw of Saudi Arabia and the U.S. and so they rebelled again in 2012. Eventually the Houthis captured the capital city, Sanaa. The Houthis did have some support from Sunni Muslims in other parts of the country, who were dissatisfied with the transitional government.

Arrayed against the Houthis are Saudi Arabia and a number of Sunni Arab states who support the presidency of Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi. At this point Hadi's presidency is a lost cause as he has so little domestic support. But the combatants continue fighting, in part because they see the conflict as one theater in the broader struggle between Sunni and Shia political power that is raging across in the Middle East.

The U.S. role in the war is substantial. Saudi Arabia buys most of its weapons from the United States. Its pilots are trained by the United States. And the United States refuels Saudi planes in the air. The U.S. military is widely believed to be helping the Saudis choose targets. And U.S. special forces are on the ground in Yemen, ostensibly to fight local al Qaeda outfits. But just as in Syria, the U.S. finds itself committed to the downfall of a Shia government, while at the same time working to degrade the ability of al Qaeda to benefit from the fall of that same government. The Saudi coalition routinely bomb civilian targets like hospitals or food production facilities. In turn, the Houthis have resorted to extreme tactics as well.

The humanitarian effect of the war has been disastrous. Over three million Yemeni people have been displaced from their homes. Another 14 million are threatened with what the U.N. calls "food insecurity," because blockading efforts and the war itself have a devastating effect on the import-dependent food supply of the nation.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But the United States does not have to continue exacerbating the situation. It's an immoral and unjust war on a population that does not threaten the United States. It contributes to the disorder and chaos in the Middle East that has benefited international terror groups. An end to the conflict would at least begin to ratchet down tensions between Saudi Arabia and Iran. (Although any realist must admit they may tick up again in Syria or in any number of conflict sites in the Middle East.)

So what should Trump do?

First, he should try an aggressive push to get Saudi Arabia to drop its support for Hadi and reduce their expectations for shaping and controlling a post-war government in Yemen. If the Saudis do not want to do that, the U.S. can and should cease all military support operations for Saudi Arabia in the war zone.

Trump's advisers may come back and explain that giving the Saudis a cold shoulder is a problem. Maybe they'll say that while Saudi Arabia may fund ISIS and other terrorist groups in Syria and Iraq, it's still a check on Iran in the region. Maybe they'll say that while the Saudis may fund mosques in Europe that are so radical refugees from the Middle East are afraid to attend them, they will keep the price of oil low and cripple Russia if we ask nicely.

If that is the case, it's a perfect opportunity for Trump to consider dramatically revising the terms of the special relationship between the United States and Saudi Arabia. Make a deal, Mr. Trump.

Michael Brendan Dougherty is senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is the founder and editor of The Slurve, a newsletter about baseball. His work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, ESPN Magazine, Slate and The American Conservative.

-

Ultimate pasta alla Norma

Ultimate pasta alla NormaThe Week Recommends White miso and eggplant enrich the flavour of this classic pasta dish

-

Death in Minneapolis: a shooting dividing the US

Death in Minneapolis: a shooting dividing the USIn the Spotlight Federal response to Renee Good’s shooting suggest priority is ‘vilifying Trump’s perceived enemies rather than informing the public’

-

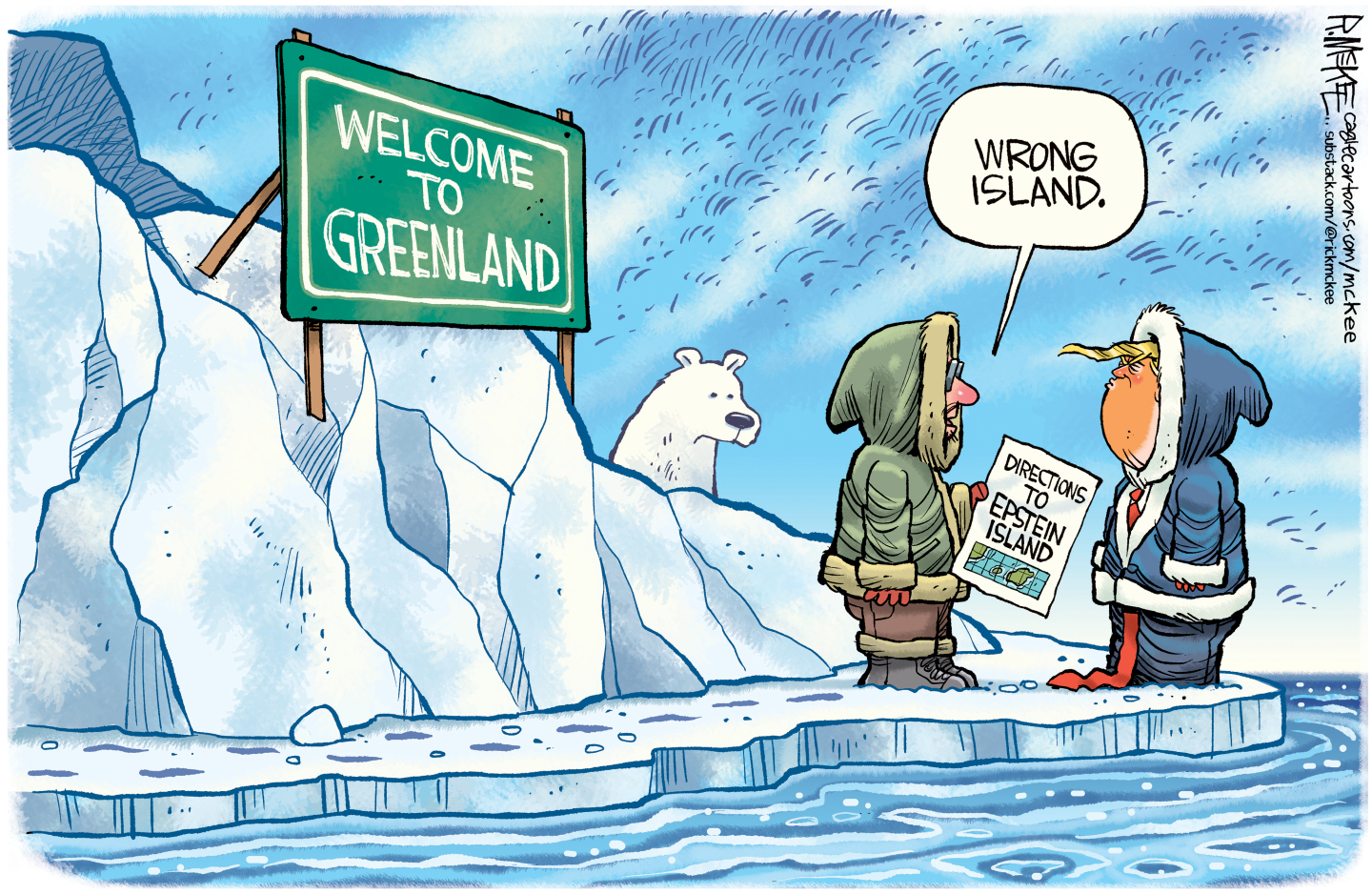

5 hilariously chilling cartoons about Trump’s plan to invade Greenland

5 hilariously chilling cartoons about Trump’s plan to invade GreenlandCartoons Artists take on misdirection, the need for Greenland, and more

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred