Steven Mnuchin bombed

Donald Trump's nominee for treasury secretary got his Senate hearing. It did not go well.

President-elect Donald Trump's nominee for treasury secretary, Steven Mnuchin, got his hearing in front of the Senate on Thursday. It did not go well.

Mnuchin's time as primary owner, CEO, and board chairman of the bank OneWest, during the 2008 financial crisis, earned him the nickname "the foreclosure king." That history played a starring role in the Senate Finance Committee hearing. In fact, the way things went down looked awfully similar to the grilling another Senate committee gave another Wall Street titan a few months ago: namely, former Wells Fargo CEO John Stumpf.

If you'll recall, a massive scandal broke last fall over revelations that Wells Fargo employees had bilked thousands of customers by signing them up for financial products they didn't request, often incurring fees in the process. In front of the Senate Banking Committee, Stumpf professed ignorance of the shenanigans and insisted he encouraged a healthy corporate culture — despite reams of documented evidence that he'd pushed the sales practices that encouraged the fraud, probably to boost Wells Fargo's stock price. The image was of a man who was either completely oblivious to the nature of the economic machine he oversaw or dissembling like mad.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Which is basically how Mnuchin came off. When pressed repeatedly by Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio), Sen. Dean Heller (D-Nev.) and Sen. Bob Casey (D-Pa.), Mnuchin ultimately confessed he had no idea how many foreclosures versus loan modifications OneWest engaged in.

It's a critical question, since foreclosures kick people out of their homes, while loan modifications allow them to keep their homes by rewriting the terms of the mortgage. At one point Mnuchin tossed out an estimate of about 100,000 loan modifications nationwide. But Casey shot back that these were extensions, which could still ultimately end in foreclosure. The truer number, Casey concluded, is probably just under 23,000 loan modifications.

We know from documentation — though Mnuchin gave the impression he didn't — that OneWest undertook 36,000 foreclosures in California alone. And Brown cited California community groups that the national number was around 60,000. "I am not aware of that," Mnuchin replied. "I have the information that's in public reports," he added at another point.

Heller has apparently pressed Mnuchin and his team on seven different occasions over the last few weeks to find out how many foreclosures OneWest carried out in Nevada, and they still don't have an answer. "As soon as I get out of this hearing I will get that information from the bank," Mnuchin said. Nor was the nominee able to speak to accusations by the U.S. Comptroller of the Currency that OneWest's mortgage practices were improper and deficient, or the leaked findings by the California attorney general's office that OneWest backdated paperwork and obstructed investigations, when Brown pressed him on both points. But he did think the leaking of the attorney general's memo was "highly innappropriate."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Ultimately, Mnuchin retreated into claims that federal regulations — particularly FDIC rules and the Home Affordable Modification Program (HAMP) — forced OneWest's hand, or that banks had way more incentives to modify than to foreclose.

But there are some problems with that, too. For one, the two claims are sort of contradictory: The FDIC reimbursed OneWest for its foreclosures to the tune of $1.2 billion, which is quite the incentive. Furthermore, research by National Consumer Law Center found that, on balance, the financial incentives to foreclose vastly outweigh the financial incentives to modify the loans.

Another wrinkle is that, for 93 percent of the loans OneWest made, it wasn't the owner. It merely serviced the loan on behalf of owners. The logic that says banks prefer loan modifications to foreclosures because the former keeps the income stream coming, only applies to banks that own the mortgages. The banks that service the mortgages often enjoy the benefits of foreclosures — fees and such — with few of the attendant costs.

Between Stumpf and now Mnuchin, this seems to be a recurring theme in the American economy: Titans of industry oversee massive economic firms and accumulate massive amounts of wealth. But then they act hurt, shocked, or even angry when people get mad at them for the devastation wrought by those same businesses.

This gets us to the one ace-in-the-hole Republicans had to play in Mnuchin's defense. Homeownership and mortgage policy under the Obama administration was basically geared towards doing what Mnuchin was doing — stabilizing the balance sheets of the big financial firms, no matter the cost to homeowners. By the time the 2008 housing bubble burst, the mortgage market was a mess of bad loans with shoddy paper trails and totally opaque chains of ownership. So the industry just started shoving as many foreclosures through the pipe as they could. And the Obama White House basically let them do it. As then-Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner said, the purpose of HAMP itself wasn't so much to save homeowners as it was to "foam the runway for the banks."

In that sense, you can kind of understand why Mnuchin was testy during the hearing. "It seems, with all due respect, that you just want to shoot questions at me and not let me explain," Mnuchin snapped at the end of one of Brown's blitzkriegs. The mortgage business in 2009 was a rotten system, and he benefited from that system. But in his defense, both sides of the aisle basically agreed on the contours of that rotten system, and the need to stabilize the financial industry above all else. Eight years later, he's suddenly getting grilled for just doing what his business was supposed to do, by people who seem crazy enough to think the world ought to operate differently.

So it was only the most pugnacious senators who had either the gumption or the credibility to really press this critique. (Which is probably why a lot of the Democrats just settled for obsessing over Mnuchin's Cayman Islands tax haven.) Stumpf, by contrast, had no such escape hatch.

It was a pretty depressing spectacle to behold, all around.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

How will the new Repayment Assistance Plan for student loans work?

How will the new Repayment Assistance Plan for student loans work?the explainer The Repayment Assistance Plan (RAP) will replace existing income-driven repayment plans

-

In the Spotlight Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro has been at odds with US forces

-

Music reviews: Ethel Cain, Amaarae, and The Black Keys

Music reviews: Ethel Cain, Amaarae, and The Black KeysFeature "Willoughby Tucker, I'll Always Love You," "Black Star," and "No Rain, No Flowers"

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: which party are the billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: which party are the billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration

-

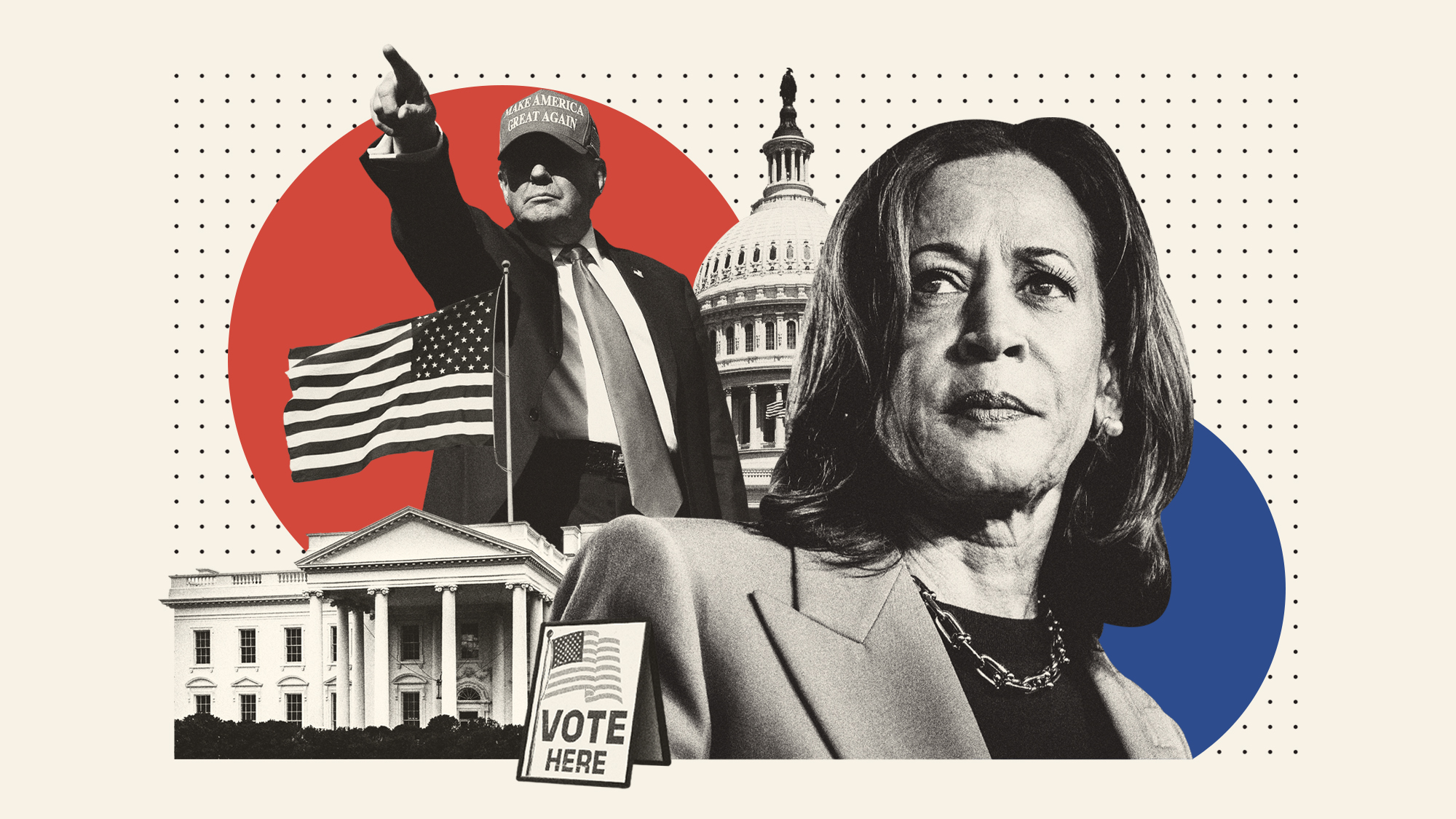

US election: where things stand with one week to go

US election: where things stand with one week to goThe Explainer Harris' lead in the polls has been narrowing in Trump's favour, but her campaign remains 'cautiously optimistic'

-

Is Trump okay?

Is Trump okay?Today's Big Question Former president's mental fitness and alleged cognitive decline firmly back in the spotlight after 'bizarre' town hall event