Rural America is more diverse than you think

It's not as poor and white as the media makes it out to be

White. Old. Disconnected. Post-industrial. Ravaged by drugs. Supportive of President Trump. Welcome to rural America! Or at least McDowell County, West Virginia.

In the past few years, this post-industrial coalscape in Appalachia has become synonymous with the decline of the American countryside, profiled at length by The New York Times, The Guardian, Al Jazeera America, and CBS News. And even more recently, it has become synonymous with President Trump. Ravaged by the fall of the coal industry, the 89-percent-white county is "the poorest, sickest, and most hopeless county in America," Reason summarized. And a staggering three-fourths of it voted for the president.

But while McDowell County is certainly symptomatic of many of the problems that inhabit the region, is it really paradigmatic of rural America as a whole? Will the Trump administration's proposed solutions — "the war on coal is over" — alleviate rural poverty overall or just McDowell County's unique woes?

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The fact is, the nation's countryside is much more diverse than the way it's usually depicted in the media. It is not a parochial homogeny defined by narrow industrial interests, but a diverse landscape with a broad sweep of economic priorities.

Take ethnic diversity. In the 10 U.S. counties with the lowest per capita income as of the 2010 census, all of which are located in rural areas, whites constituted more than 61 percent of the population in only three. Whites were the minority in four of these counties. This does not account for households that may have a clear reason not to complete the census due to the presence of residents who may be living in the country without documentation. At the same time, while Trump did indeed do very well in rural America — he won by a margin of 62 percent to 34 percent in small towns — an election is an equally imperfect measure of who lives in a given place, especially considering the disproportionate impact of voter suppression measures upon minority voters.

The overall picture of rural economic wellbeing can likewise not be explained by one community alone.

Though urban employment has grown twice as quickly as rural employment since the 2008 financial crisis, central states to the west of the Mississippi from Texas and Louisiana all the way up to the Canadian border were generally less affected by the impact of the recession. This was in part the consequence of a favorable composition of industries with a greater emphasis on agricultural and extractive production.

North Dakota, for instance, site of a quintessentially rural revolt led by Native Americans at Standing Rock (population 8,217) in the past year, experienced the lowest statewide rise in unemployment between the end of 2007 and the start of 2010, and has been subject to a shale oil boom that has attracted a diverse mix of incoming workers from across the nation. Eight percent of jobs in North Dakota are in construction and extraction — double the national average.

And while you may have heard of the fracking boom, have you heard of the chicken boom? As red meat consumption has declined over the past three decades, chicken consumption has risen steadily. And America's new favorite form of protein has maintained a strong demand for labor in primarily rural communities. Of the 426 commercial poultry slaughtering operations in the United States, 314 are located in towns that registered less than 20,000 people in the 2010 census, while 21 are based in unincorporated townships. But the workers in the industry aren't the white working class you'll find in so many media profiles. Historically, the majority of poultry jobs were held by black workers, but in the 1990s, a Central American labor force took over. Now, the industry is acting as the driving force in the creation of new rural communities of Somali, Iraqi, Eritrean, and Syrian refugees.

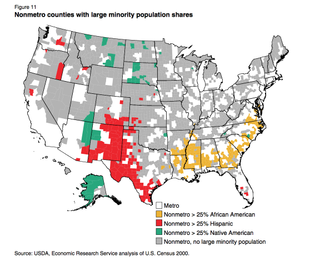

This is not to say all is well in rural America. While non-metropolitan counties with a greater than 25 percent Hispanic population, mostly in the Southwest, rose in employment in the early 2010s, unemployment in non-metro counties with a greater than 25 percent African-American population, mostly in the Old South, were disproportionately hurt. These counties were often closer to metropolitan areas and more densely populated — two additional factors which significantly relate to job loss in rural America — with an industrial mix more closely skewed towards the unstable demand for certain manufactured goods.

All of which is to say that rural life is more complicated than the picture of a red barn and a weather vane that may appear on the packaging for your meat or milk bottle. Just like timber and fishing, both fracking and livestock farming create economic opportunities as well as environmental problems.

Stories that pit cities against the countryside are powerful and succeed in highlighting important contrasts in the way the country has evolved, but they are also reductive. Just as there is little insight to be gained by lumping Baltimore with Manhattan, there is little to be learned by grouping the mountains of West Virginia with the plains of North Dakota. There are more than two Americas, and each deserves its own analysis.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Patrick Dixon is a research analyst at the Kalmanovitz Initiative for Labor and the Working Poor at Georgetown University.

-

Is this the end of cigarettes?

Is this the end of cigarettes?Today's Big Question An FDA rule targets nicotine addiction

By Joel Mathis, The Week US Published

-

A beginner's guide to exploring the Amazon

A beginner's guide to exploring the AmazonThe Week Recommends Trek carefully — and respectfully — in the world's largest rainforest

By Catherine Garcia, The Week US Published

-

What is the future of the International Space Station?

What is the future of the International Space Station?In the Spotlight A fiery retirement, launching the era of private space stations

By Joel Mathis, The Week US Published

-

Can a media correction ever really match the mistake?

Can a media correction ever really match the mistake?The Explainer There has to be a better way

By Marc Ambinder Published

-

Did the media get Ferguson wrong?

Did the media get Ferguson wrong?feature What we thought we knew about Ferguson is very likely not what actually happened

By Marc Ambinder Last updated

-

Stop making fun of CNN's all-plane-mystery, all-the-time coverage

Stop making fun of CNN's all-plane-mystery, all-the-time coveragefeature The network's critics are sourpusses

By Marc Ambinder Last updated

-

Media bias and the abortionist

Media bias and the abortionistfeature

By Marc Ambinder Last updated