Why Charlottesville is a turning point

This is often how change happens: one unpredictable, seemingly small event that sends out ripples of reaction that reshape the political terrain

When we look back on the history of the Trump presidency, this week will likely be seen as a key series of events. We've seen multiple members of the Republican Party criticize the president and make strong statements about white nationalists, white supremacists, and neo-Nazis. We've seen corporate CEOs abandon White House advisory councils in disgust; the members of one such council decided to disband entirely, whereupon President Trump quickly announced he was shutting it down, in a laughable "You can't quit, I'm firing you!" attempt at face-saving. We've seen Trump's approval ratings fall even farther than they had before. We've seen Confederate statues quickly dismantled in Baltimore, and the governor of North Carolina come out in favor of taking down all the Confederate monuments in his state. And you can bet that the issue of the Republican Party's relationship with the far right will come up again and again, all because of a protest in Charlottesville that was not unlike others, until a car barreled into a crowd of people, killing one.

This is often how change happens: one unpredictable, seemingly small event that sends out ripples of reaction that reshape the political terrain.

That's certainly what the different sides in Charlottesville wanted, in their own ways. The "Unite the Right" rally, ostensibly to protest the potential removal of a statue of Robert E. Lee, was meant to show the country that white supremacists and neo-Nazis are a strong, numerous, and potent force. The counter-protesters came to show the country that the rest of us won't tolerate that kind of hatred in our communities.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Everyone brought their phones to document the events, and the news media showed up too, drawn to the potential for conflict (and the fact that they could get there from Washington in a couple of hours). Had it not been for the photographs and video that were collected and disseminated, we would not be having this discussion. The shots of protesters with arms raised in Nazi salutes, their faces contorted in anger, that extraordinary photo of bodies flying through the air after being hit by a car driven by a neo-Nazi protester, video of the car shooting through the streets as people screamed — all of it made the truth of the event impossible to deny or ignore.

Well, maybe not for everyone. President Trump insisted that both sides were equally to blame, an interpretation belied by what people had seen on the news. It showed that even for someone who has been obsessed by his own media coverage for the entirety of his adult life, Trump doesn't grasp the power of images to shape how we think of events.

Unlike Trump, smart politicians understand how to use the common experience of news events to make the case for their own agenda. This was always true, but it became much more dependent on visual imagery once television allowed us all to see what had happened, or at least some version of what had happened. Civil rights activists understood that power; it was key to their strategy of nonviolent confrontation. When they stood before lines of baton-wielding police and fire hoses, they knew that the beatings and abuse they would endure would be shown on the news and would force whites around the country to make a moral choice, one that had been avoided for too long.

No president appreciated the power of imagery more than Ronald Reagan, who never lost an opportunity to utilize shared visual experiences for his own goals. As Kathleen Hall Jamieson wrote in her 1988 book Eloquence in an Electronic Age, "Whenever possible, Reagan builds his arguments from a visual scene that he and the nation have recently experienced." Reagan was an excellent storyteller, and he would retell stories of what had just happened, always with specific and vivid references to the scenes everyone had witnessed. In that way he situated himself as part of the audience, in which all Americans had the same perspective in their identity as television viewers.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Donald Trump is not a particularly good storyteller, since he possesses neither eloquence nor an appreciation for human emotion and relationships. The best he can muster is anger over something he wants other people to be angry about, like the murder of a young woman by an undocumented immigrant. Inevitably, he describes the victim as "beautiful," as though her value as a human being could only be proven by her good looks (on Wednesday he tweeted, "Memorial service today for beautiful and incredible Heather Heyer, a truly special young woman. She will be long remembered by all!").

But he often seems surprised at how his words are received, which is why we'll be left with another image from this week: that of President Trump standing in the gold-mirrored lobby of Trump Tower in New York, angrily insisting on a moral equivalence between the neo-Nazis who came to Charlottesville and the counter-protesters who met them there, snarling at the incredulous reporters while his aides grimaced in the background. Not that anyone was surprised to hear Trump express the repellent views we knew he had; perhaps what was most amazing was how politically tone-deaf it all was.

Judged by the number of people involved or even the loss of life, Charlottesville pales in comparison to many other key political moments in American history, protests or confrontations or outright massacres. But it looks like it will produce a profound shift, changing the seriousness with which we take the emboldened racist right, the divisions within the Republican Party, and the way Americans look at Donald Trump. It's hard to know yet how far its impact will reach, but seen from today it appears that it's something we'll be talking about and referring to for years to come. As well we should.

Paul Waldman is a senior writer with The American Prospect magazine and a blogger for The Washington Post. His writing has appeared in dozens of newspapers, magazines, and web sites, and he is the author or co-author of four books on media and politics.

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

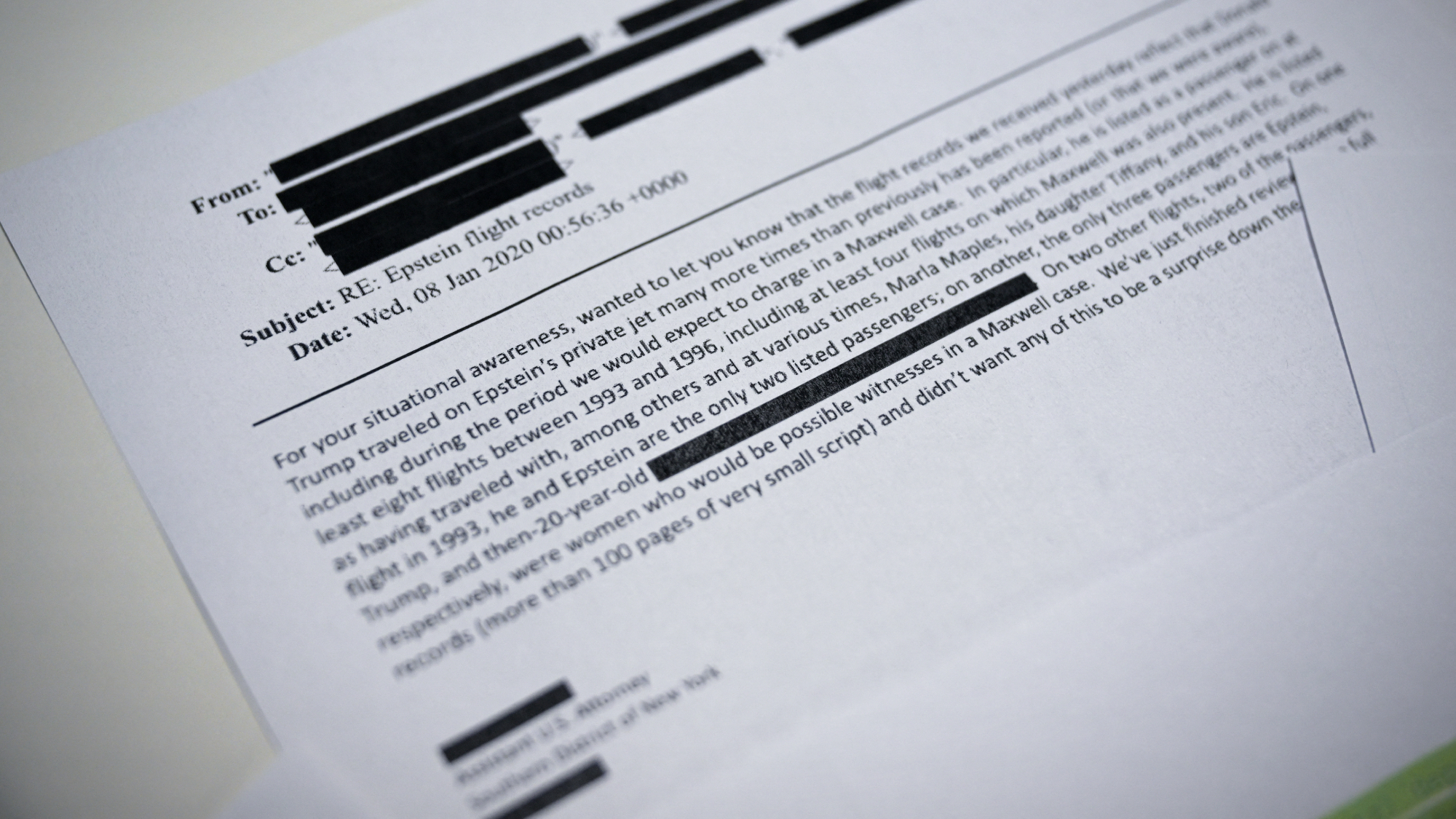

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook