The surprisingly fascinating politics of The Walking Dead

How a show about zombies speaks to our cultural moment

Though AMC's The Walking Dead debuted in 2010, the zombie drama is still widely viewed as an entertaining spectacle that, on occasion, poses very broad questions about morality and survival in a world without laws. Mad Men's Don Draper went spelunking for the meaning of human happiness in Old Fashioned after Old Fashioned, and Breaking Bad's Walter White interrogated the nature of power through many a searing monologue and well-placed explosive. The Walking Dead, on its surface, favors a more dorm-room kind of existentialism: Like, I mean, if you had to, like, kill a bunch of people, for you and your family to live, like, would you do it?

The show's seven seasons have followed small-town sheriff Rick Grimes (Andrew Lincoln) as he wakes from a coma, bands together with a ragtag group of survivors (is there any other kind?) who'd never have anything to do with each other in the days before the end of days, is grizzled and hardened by catastrophic losses and betrayals, and, oh yes, grows a very gnarly beard. In its last several seasons, The Walking Dead has delivered more moments of extremis than moments of insight — season 7 began as the new Big Bad, a sneering, leather-jacketed warlord named Negan (Jeffrey Dean Morgan) plays eeny-meeny-miny-moe before beating two fan favorite characters to death with a barbed wire-wrapped baseball bat; it ended with a giant CGI tiger named Shiva saving Rick's son Carl (Chandler Riggs) just as he's about to meet the business end of that baseball bat.

One could argue that The Walking Dead has reached a tonal nadir, where everything is either God No or Hell Yeah — a definite letdown from the George A. Romero zombie flicks that it wants to claim as its spiritual kin. However, as the show enters its eighth season, and commemorates its 100th episode, in a decidedly new social and political climate — where the powers that be play eeny-meeny-miny-moe with people's civil rights, and with the safety of the world itself, every day — The Walking Dead merits another appraisal. Though it may not be Prestige TV™, it does speak uniquely to our current cultural moment, and it is now, at times, surprisingly (if selectively) progressive.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The series has always been preoccupied with the question of what, exactly, makes a good leader. It is specifically interested in why some survivors crater to obedience and fear, and fall enthralled under a strongman's sway: The joie de vivre that Negan brings to hurting people does feel distinctly Trumpian (especially if one considers a Twitter rant as legitimate villain monologuing) — as does his repeated promise to give more than just a homestead, but a way of life, a merciful freedom from thought, to his followers. Negan's inverse is in The Governor (David Morrissey), ruler of the Woodbury township, who models a subtler, snake-tongued appeal of might-makes-right in a world where everything has gone hideously wrong.

The Governor attires his violence (which includes forcing prisoners into gladiatorial matches, or threatening them with sexual assault) in the fine vestments of civilization: His little town seems untouched by the festering menace outside of its walls; it hums along on a sweet nostalgia for a Mayberry kind of hominess, complete with little shops and pretty gardens, and even electricity — so his citizens can easily, even gratefully, ignore the more barbarous ways he preserves their precious order. For Romero, the gnashing hordes of the undead reflect the bias and greed that animate (or should I say, reanimate) contemporary conservatism — but on The Walking Dead, the titular masses represent the fear of the terrible Other (the refugee terrorist, the liberal "snowflake," and the Black Lives Matter activists who "hate the flag and troops and freedom") who threaten a supposedly quintessential American way of life.

The Other is what makes leaders like the Governor or Negan so terribly appealing to so many people: They make the boot heel between the shoulder blades feel like an affirming hand on the back. The series wants to place Rick on a razor-wire tightrope between becoming a strongman himself (instigating a "Ricktatorship") and participating in a more balanced, egalitarian system of governance. However, it often repositions him as a John Wayne model of inherent white dudely virtue (the marketing materials for season 8 put Rick in a downright messianic milieu), when Rick's belief that his might really does make right has emboldened him to make decisions that range from breathtakingly boneheaded (like when he led the group to a compound full of cannibals) to just plain cruel. His macho certitude puts the whole gory storyline of "All Out War" into motion: After he hears about The Saviors, Rick technically invades their turf first, ordering his crew to kill several of them in their beds. Which, of course, we'd see as rightfully deplorable if, say, Negan or The Governor, or any leader who wasn't "our guy," our "hero," had ordered it. The Walking Dead as implicit, if unintentional, critique of white male exceptionalism — damn, who'd have thunk it?

Watching Rick blunder and thousand-yard-stare and grandly speechify is like finding only Werther's Originals in your Halloween candy bucket — you suck on that benign staleness because it's all you have, but you pine for the buttery sumptuousness of a real treat. And for years, Rick really was all we had. Now, however, The Walking Dead has surrounded him with an infinitely more compelling array of supporting characters. The fact that these characters are mostly women, and people of color, is a remarkable turnabout — in the earlier years, women were a combination of love interest, harpy, and victim (with Rick's wife, Lori, a particularly noxious embodiment of all three; she existed only so that she could die in childbirth and inspire a full season's worth of epic manpain). And people of color, especially black men, were the zombie-world equivalent of redshirts. The core group's first (and, for a long time only) black member was named (ahem) T-Dogg, and he remains more notable for the spectacular grisliness of his death — ripped to bits as he rescues a nice white lady — than anything he accomplishes in life.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In recent seasons, The Walking Dead vested these characters with a struggle and pathos that feels more authentic, and provocative, than anything Rick "they messed with the wrong people" Grimes has experienced. At its most latter-day satisfying, The Walking Dead uses these supporting characters to reconfigure notions of bravery, and identity. Father Gabriel (Seth Gilliam), the cleric who literally barricaded himself in his church as his parishioners were devoured, learns to screw his courage to the sticking place; his moments of cunning and valor — like when he lies to Negan about the whereabouts of a fellow survivor — are more resonant, and more relatable, because they're harder-fought. The best arcs now involve people who were summarily disenfranchised pre-zombie nation stepping into their own versions of purpose and power: Ex-football star Tyreese (Chad Coleman) finds his meaning in caring for the group's young children, while his sister Sasha (Sonequa Martin-Green) becomes an ace sniper.

Sasha joins a sorority of warrior-women that includes Maggie (Lauren Cohan), the dimple-cheeked farmer's daughter turned leader of the Hilltop commune; Carol (Melissa McBride) battered wife-turned-Rambo; and Michonne (Danai Gurira), the katana-wielding lady samurai whose arc has interrogated the standard "strong female character" stoicism by pushing her into greater states of connectedness and vulnerability through a love affair with Rick. This relationship is especially significant; as pop culture writer Black Girl Nerds puts it, "There are few actresses who share the aesthetics of Danai Gurira. Rarer still have we seen them as a lead, or the 'love interest.' … The Walking Dead … is in the position to make an impact on how dark skinned black women are loved and nurtured on screen." Women on The Walking Dead are no longer weak-willed nags, but they're also more than just bodacious fighting machines — they can kick ass and love deeply, lead communities, and, at times, experience a very human revulsion at the carnage of their world.

This transformation is most robustly evident in Carol's slow evolution from abuse victim to a surrealistically hyper-competent survivor (remember that cannibal compound that Rick blunderingly led the group to? Carol takes it out with a machine gun and a rocket-launcher, single-handedly). And there's something downright radical in turning a middle-aged woman into an action heroine with her own rabid fan base (one of the most popular Walking Dead memes is, "If Carol Dies, We Riot"). On a deeper level, the show suggests that, since every day in Carol's house was a personal apocalypse, she is uniquely prepared for the real deal writ large, able to depersonalize the violence she must dole out — until, of course, she can't. Characters like Carol or Morgan best exemplify the deep soul-weariness of living in a state of sustained violence.

In letting these characters form its moral axis — in ways that Rick, with his more traditional kinds of privilege and attendant ego, simply can't — The Walking Dead seems to acknowledge, albeit somewhat unconsciously, that its great white hype of a hero is not its most compelling feature. Even though the "All Out War" arc, and so many arcs to come, will still no doubt center on Rick's abiding sense of grievance, and his struggles at being a better leader than the Negans and the Governors of the world, the show is leaning on its more diverse, and compelling, range of supporting players (who would, in a more just world, be the stars of their own shows) to tell meaningful stories. And even Rick now serves as a cautionary tale about a certain kind of will-to-power. Though it will never be Dostoevsky, or even Better Call Saul, in the grand scale of depth and profundity, The Walking Dead might have something truly smart to say about our current moment after all.

Laura Bogart is a featured writer for Salon and a regular contributor to DAME magazine. Her work has appeared in The Atlantic, CityLab, The Guardian, SPIN, Complex, IndieWire, GOOD, and Refinery29, among other publications. Her first novel, Don't You Know That I Love You?, is forthcoming from Dzanc.

-

Trump fears impeachment if GOP loses midterms

Trump fears impeachment if GOP loses midtermsSpeed Read ‘You got to win the midterms,’ the president said

-

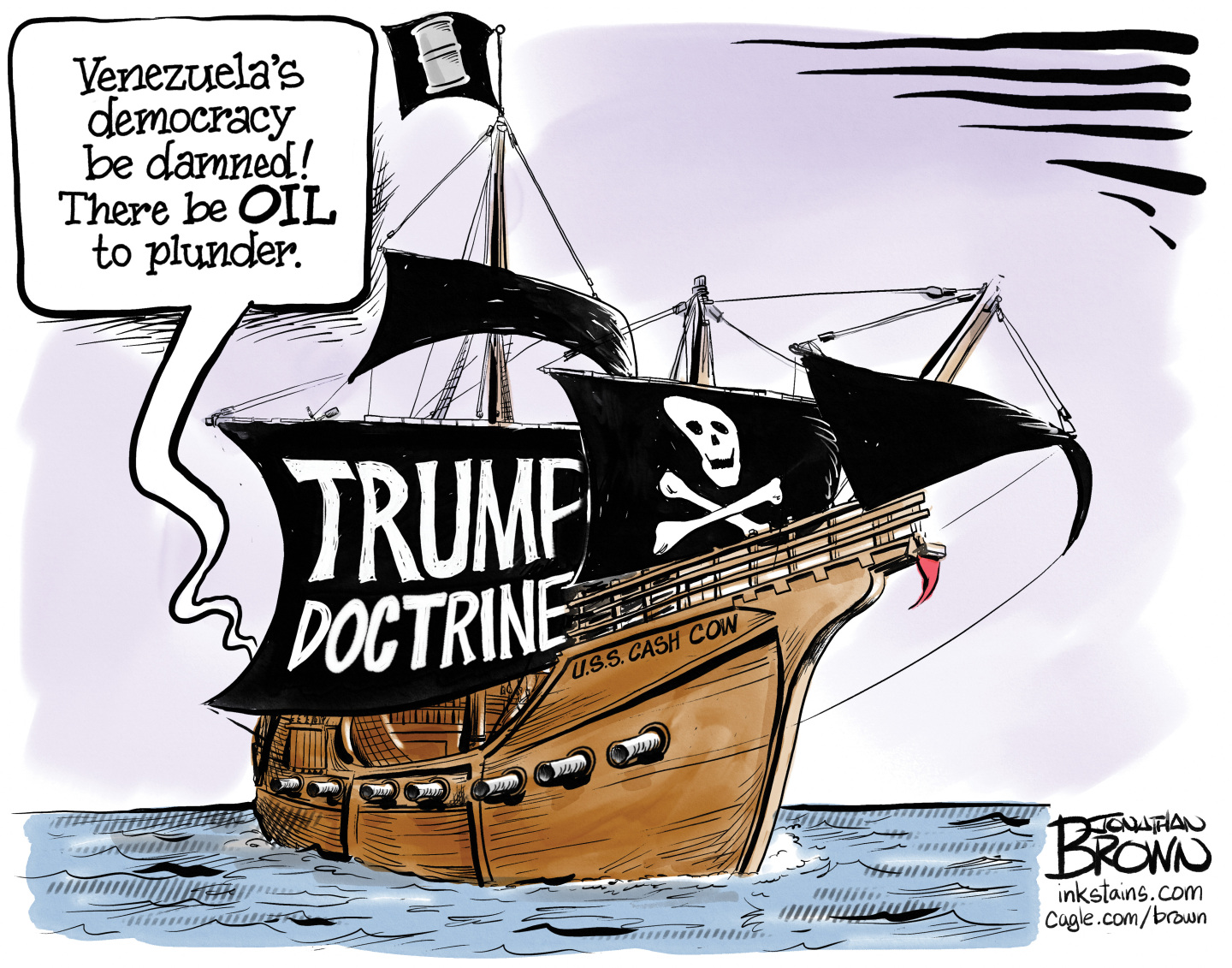

Political cartoons for January 7

Political cartoons for January 7Cartoons Wednesday's political cartoons include plundering pirates, nomenclature legislature, and more

-

Trump’s Greenland threats overshadow Ukraine talks

Trump’s Greenland threats overshadow Ukraine talksSpeed Read The Danish prime minister said Trump’s threats should be taken seriously

-

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'The latest biography on the elusive tech mogul is causing a stir among critics

-

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!The Explainer Please allow us to reintroduce ourselves

-

The Oscars finale was a heartless disaster

The Oscars finale was a heartless disasterThe Explainer A calculated attempt at emotional manipulation goes very wrong

-

Most awkward awards show ever?

Most awkward awards show ever?The Explainer The best, worst, and most shocking moments from a chaotic Golden Globes

-

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. deal

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. dealThe Explainer Could what's terrible for theaters be good for creators?

-

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'The Explainer Move over, Sam Elliott and Morgan Freeman

-

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020feature So long, Oscar. Hello, Booker.

-

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortality

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortalityThe Explainer This film isn't about the pandemic. But it can help viewers confront their fears about death.