Betsy DeVos is dealing a huge blow to campus rape victims

The education secretary is utterly wrong about how universities should handle assault allegations

On Friday, Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos unveiled a plan to roll back Title IX protections in higher education for victims of sexual assault and harassment. Arguing that "if everything is harassment, nothing is," DeVos promised to change Obama-era regulations designed to put accusers and the accused on equal footing in disciplinary proceedings.

That Title IX is one of the first major issues in education that the DeVos regime chose to tackle is revealing. The coming assault on protections for rape victims as an early priority is very much in keeping with this administration's broad circle of abusers and apologists for violence against women, starting at the very top. They have all bought into the absurd lie that American society in general, and colleges in particular, treat accused rapists too harshly. And now they are about to dismantle protections for victims at the very institutions that have made the most progress in combating rape.

Title IX is a 1972 law that requires universities that receive federal funding (which amounts to almost all of them) to avoid any form of discrimination based on gender, sexual orientation, or gender presentation. Title IX was invoked, for instance, in the long struggle to secure equal funding for women's athletic programs. And in an April 4, 2011 letter, the Office of Civil Rights informed the industry that it would begin holding universities accountable, under Title IX, if they failed to comply with a series of new recommendations for how sexual assault and harassment should be investigated.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

There were two very important changes ushered in by the new recommendations: One was to lower the standard of proof by employing the civil law concept of "preponderance of the evidence" — meaning the accused can be found responsible if it seems more likely than not that the allegation is true. This is a substantially lower bar to clear than the "beyond a reasonable doubt" standards used in criminal cases. The other change was to discourage cross-examination of accusers by the accused personally (and vice versa), for fear that such practices lead fewer victims to come forward. The 2011 letter made it clear that if the university allows lawyers to be present, they must be available to both parties, and that the accused should also be able to present evidence and call witnesses.

After the letter was released, colleges and universities scrambled to put more serious frameworks in place. It was uneven and sometimes chaotic process. But overall the policy change was welcomed by anti-rape activists and clearly led presidents and provosts to invest greater resources in the problem. No longer could universities sweep campus assaults under the rug by, for instance, having victims sign non-disclosure agreements and driving survivors off campus altogether by leaving accused rapists in classes and dorms. They would need to investigate claims quickly, and put coherent internal procedures into place to conduct reviews.

It is these internal reviews that have proven most controversial. Critics are outraged that internal proceedings are governed by the new standards of evidence. What business, they ask, does some kangaroo court stuffed with distracted faculty members and admissions officers have passing judgment on complex legal matters? But if no one objects when multi-million dollar judgments are passed down in civil courts, why is expelling or sanctioning a student based on these standards somehow a bridge too far when applied to rapists? What about when students are kicked out for plagiarism or honor code violations? Such proceedings also can have a serious impact on a student's life trajectory. Do you think there's a jury impaneled every time a student gets kicked out of school for passing a Wikipedia entry off as a research paper?

There is not. And students don't have the right to personally cross-examine professors any more than they should have the right to interrogate their accuser in a rape case.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What evidentiary standard do you imagine is used by the civil courts that rapists and their parents run to after their universities expel them? If you guessed "preponderance of evidence," you get a cookie. Why should men accused of rape on college campuses be subject to an entirely different standard of evidence than the whole rest of the civil court system in the United States?

Reactionaries have been plotting this move for years. Earl Ehrhart, a Georgia state legislator, backed a bill that would make it illegal for universities to start an internal investigation unless a police inquiry had already begun. DeVos, of course, granted him a meeting. Tellingly, DeVos also met with so-called "men's rights activists," including the National Coalition of Men. The NCM is a better-dressed, more presentable face for a movement that occupies an odious corner of the alt-right, where the preposterous idea that men are routinely prosecuted for rapes they did not commit is orthodoxy. The reality is that the overwhelming majority of rape and assault accusations are never prosecuted at all. On campus, fewer than a third of students found guilty of rape, assault, or other forms of sexual misconduct are actually expelled from school. But critics seem to want universities out of the investigation business altogether.

It just doesn't work that way. Universities do not have the luxury of waiting for legal processes to play out. This is really not that hard to understand. If you are accused of rape or sexual misconduct in a corporate workplace, the corporation must have procedures in place to determine your employment status and to protect the victim from further abuse, even if the allegation turns out to be false. Otherwise the company is opening itself up to massive legal (and of course moral) liability. Even if the alleged crime is referred to the police, the company can't just sit around and wait for what could be a years-long legal process to play out.

Why are universities any different? Certainly, there is room for a conversation about how internal investigations should be structured. But these critiques aren't, by and large, a plea for better-thought-out ways of addressing the problem — they are part of a moral panic that is embedded in right-wing discourse about how colleges and universities are hotbeds of leftist totalitarianism. They perpetuate the rape culture double standard by which men's "lives are ruined" by an allegation but a survivor needs to be able to sit next to her assaulter at tomorrow's philosophy seminar and pretend like nothing happened.

Scratch a quarter-inch under the surface of any of these characters, like Acting Assistant Secretary of the Office of Civil Rights Candice Jackson, and you'll find that they believe most rapes are just "bad sex" that accusers regret. They don't want just to change the rules at universities, they want to make rape functionally impossible to prosecute outside of the extremely small universe of violent assaults by strangers.

In rescinding these Title IX protections, Betsy DeVos has revealed that she cares more for the reputations of rapists than she does for the rights and well-being of their victims, a bias which is shared by her boss, is deeply embedded in the contemporary Republican Party, and judging from press reactions, is also quite pervasive in American society generally. For activists who believed that society was finally making progress toward a better understanding of rape and how to fight it, Friday's news was incredibly dispiriting, and a reminder of how much more work remains to be done.

David Faris is a professor of political science at Roosevelt University and the author of "It's Time to Fight Dirty: How Democrats Can Build a Lasting Majority in American Politics." He's a frequent contributor to Newsweek and Slate, and his work has appeared in The Washington Post, The New Republic and The Nation, among others.

-

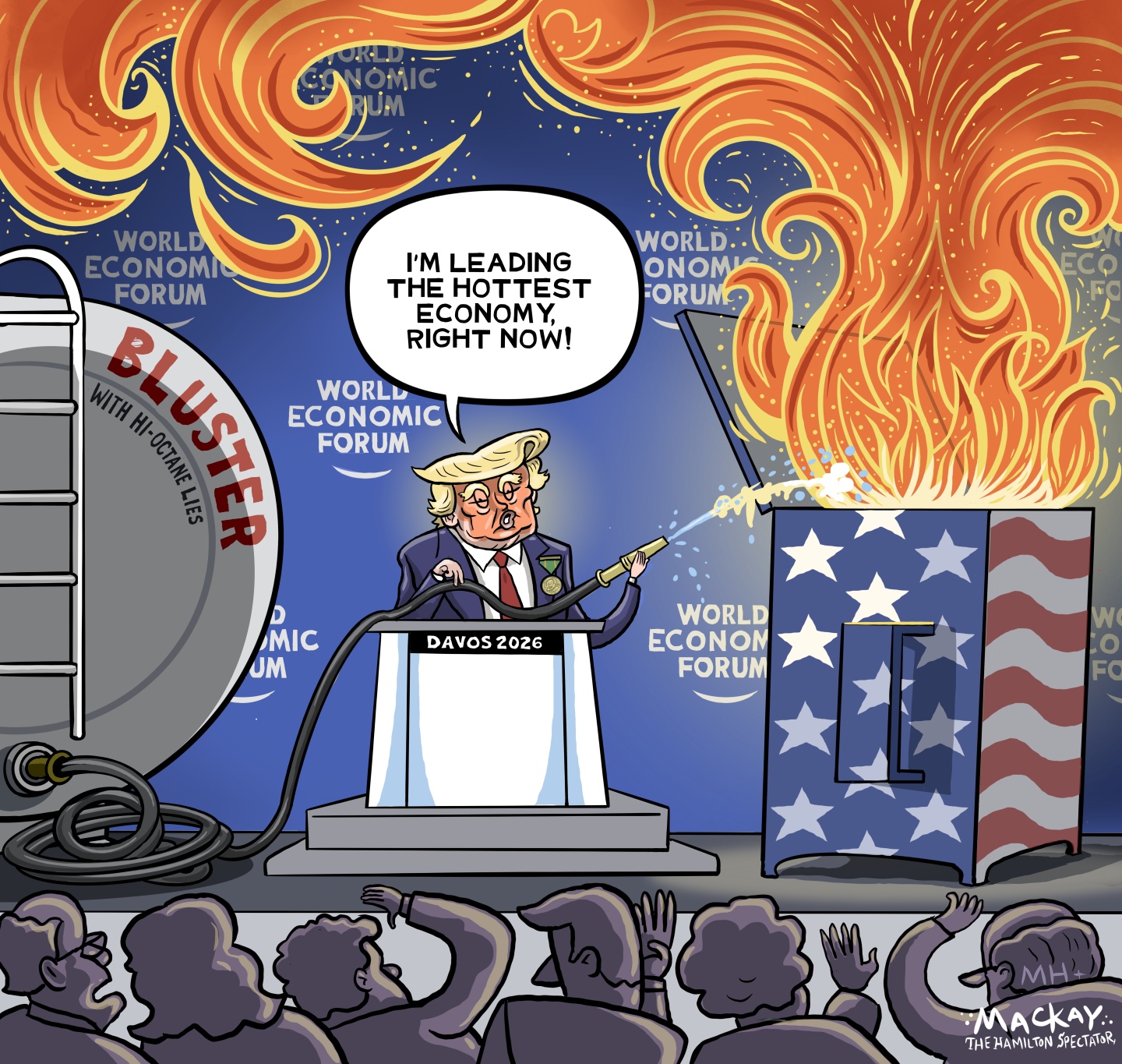

Political cartoons for January 25

Political cartoons for January 25Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include a hot economy, A.I. wisdom, and more

-

Le Pen back in the dock: the trial that’s shaking France

Le Pen back in the dock: the trial that’s shaking FranceIn the Spotlight Appealing her four-year conviction for embezzlement, the Rassemblement National leader faces an uncertain political future, whatever the result

-

The doctors’ strikes

The doctors’ strikesThe Explainer Resident doctors working for NHS England are currently voting on whether to go out on strike again this year

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred