This year's awful Super Bowl ads show America's corporations are freaking out

The nation is divided, and advertisers don't know who they're targeting anymore

We are at such a rudderless point in this country's history that the only symbols companies feel safe deploying are dead. The Super Bowl — that annual American celebration of ads and competitive violence — packaged a fascinating game between the Eagles and the Patriots into a commercial framework so baffled by the divided audiences it was trying to serve that it ended up grabbing at ghosts.

I mean that literally. The controversy surrounding Justin Timberlake's plans to perform with a hologram of Prince — who died in 2016, and who famously and fervently hated stunts of that sort — predicted a larger trend in the proceedings: Martin Luther King, Jr. and Kurt Cobain were also exhumed to serve a message they wouldn't approve of in order to court a divided public. Companies tried to use the dead to unify a public that no longer really shares any living heroes. The problem seems to be that there's no longer any straightforward "American" demographic for ad agencies to safely target.

The majority of this year's Super Bowl ads weren't memorable, or good, or funny, or principled. Some, like ads for The Voice and Tide, were entertaining meta-commentaries on the genre of the ad itself. A choice few, like the Blacture ad, which featured a blindfolded black man with his mouth taped shut, were startling and effective provocations. But most of the ads were baffled and timid and just plain weird.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

One way Corporate America haplessly straddled the divide between right and left was by scuttling logic. Take Hyundai: Perhaps trying to sanitize the security state we've become now that guns are everywhere and mass shootings are routine, the car company presented a nerve-jangling ad in which Super Bowl attendees are obediently standing in a security line to go through metal detectors, like Americans have learned to do. Some are pulled out and taken to another room. It is concerning. It looks like they're about to be strip-searched or profiled or questioned. The happy twist is that they're shown a video of some cancer survivors, whom they then … get to meet. It is proposed that this connects somehow to car ownership and hope.

This message confusion was everywhere, with a vaguely dystopian subtext. Latching on to the rash of natural disasters last year, Stella Artois and Budweiser both swapped out their hedonistic good-time messaging for a tenuous link between beer and charitable water. Citing that one-third of Americans, living paycheck to paycheck, have no retirement savings, E-Trade showed old people working in various industries to the strains of "Day-O." The grim implication: You should invest that income you don't have! As if to drive home the misery of the present, an ad for a new Kia car showed Steven Tyler driving in circles into the past.

T-Mobile's ad should have been a straightforward defense of multiculturalism — it featured adorable babies of all races and described a better world that would give them all equal opportunity. But if you listened closely to the lullaby, you recognized Nirvana's "All Apologies," the Kurt Cobain song featuring lyrics like "everything is my fault / I'll take all the blame" and "choking on the ashes of her enemy." The ode to human potential pairs oddly with suicidal ennui.

But the greatest monument to America's muddled, nostalgic conversation with itself is undoubtedly the 2018 Super Bowl Dodge ad. The Ram commercial celebrates marching troops and resource-gobbling trucks to the solemn strains of the Rev. Martin Luther King's "Drum Major Instinct" sermon. It's a distasteful and unsettling pairing. But it gets worse when you realize (as many have pointed out) that King specifically warned against the evils of consumerism — cars in particular. A genius redubbed the commercial with what King actually said about commercialism and cars.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But you can see what they were trying for. The dead were supposed to lend cover and coherence to these efforts to market products to an America that no longer quite coheres. Justin Timberlake — who first appeared at the Super Bowl thanks to headliner Janet Jackson (to her career-derailing detriment) — didn't invite any big names to share the stage with him. Like Dodge and T-Mobile, he included a dead icon instead — one with whom he'd had some public spats. It partly worked! The resulting spectacle was jubilant within the confines of the stadium and pretty divisive outside of it.

How did we get to these strange corporate contortions, these confused nods to multiple perspectives that flail in search of a market?

Well, companies are feeling shy in the wake of the boycott wars of 2017. This Super Bowl was being boycotted from both sides: by those on the left angered by Colin Kaepernick's exclusion from the league, and by those on the right angered by players kneeling — or by the political ads that ran at the Super Bowl last year.

Last year's Super Bowl ads were more clear. Last year, corporate America took a firm stand against the new administration's contempt for immigrants. Budweiser ran an ad that portrayed its founder's journey to America, highlighting the ways he was mistreated here (in those distant, blinkered times) for the crime of being foreign. 84 Lumber ran an ad in which a mother and daughter try to emigrate to the United States from Mexico. Those ads were pointed. They were direct.

But the atmosphere was such that right-wing viewers read attacks on the president even into the sorts of anodyne messages that have always powered American capitalism. A 2014 Coca-Cola ad (which no one dreamed of objecting to when it first ran) sent the far-right into conniptions when it ran again before the 2017 Super Bowl. Why? Because they'd been taught by then to take any inclusive message as an attack, to the point where they objected to the fact that a song extolling America was sung by a variety of people in languages that were not exclusively English.

That Coke ad was the perfect test for how the president had inflamed latent xenophobic tendencies in his cowed and fearful base. Cloistered, cringing, America belonged to them alone. They hated even hearing it praised in other languages. Paranoia needs a persecutor, so when the president pointed at hard-working immigrants, his followers took the bait.

2017 ended up being a tough year for the NFL. In desperate need of some winnable controversy, a historically unpopular president incited his base against a small group of football players who knelt to silently but publicly protest the consequence-free killing of unarmed black people by police. That unarmed American citizens ought not to be executed by police used to be a rather moderate position. But the president called NFL players "sons of bitches" for daring to object. He called for boycotts. He used Twitter and the right-wing media machine to mischaracterize #TakeaKnee as a protest of the flag itself and an act of "disrespect" to veterans. (The insulting implication is that veterans wouldn't object to Americans being executed without due process or just cause.)

Corporations freaked out. Worried that any message of inclusion, however mealy-mouthed, might anger the Trumpian third, many opted for the strange attempts at ideological compromise we saw during this year's Super Bowl.

Last night, an excellent football game was scaffolded by a pretty fascinating illustration of just how bizarre "bipartisan capitalism" can look in this new America. The effect was disjointed and vaguely depressive. The grim gamble was that the only icons both sides would accept were dead. But at a moment in which everything is askew, that was wrong too.

Lili Loofbourow is the culture critic at TheWeek.com. She's also a special correspondent for the Los Angeles Review of Books and an editor for Beyond Criticism, a Bloomsbury Academic series dedicated to formally experimental criticism. Her writing has appeared in a variety of venues including The Guardian, Salon, The New York Times Magazine, The New Republic, and Slate.

-

8 restaurants that are exactly what you need this winter

8 restaurants that are exactly what you need this winterThe Week Recommends Old standards and exciting newcomers alike

-

‘This is a structural weakening of elder protections’

‘This is a structural weakening of elder protections’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

4 tips to safeguard your accounts against data breaches

4 tips to safeguard your accounts against data breachesThe Explainer Even once you have been victimized, there are steps you can take to minimize the damage

-

The hottest Super Bowl ad trend? Not running an ad.

The hottest Super Bowl ad trend? Not running an ad.The Explainer The big game will showcase a variety of savvy — or cynical? — pandemic PR strategies

-

Tom Brady bet on himself. So did Bill Belichick.

Tom Brady bet on himself. So did Bill Belichick.The Explainer How to make sense of the Boston massacre

-

The 13 most exciting moments of Super Bowl LIII

The 13 most exciting moments of Super Bowl LIIIThe Explainer Most boring Super Bowl ... ever?

-

The enduring appeal of Michigan vs. Ohio State

The enduring appeal of Michigan vs. Ohio StateThe Explainer I and millions of other people in these two cold post-industrial states would not miss The Game for anything this side of heaven

-

When sports teams fleece taxpayers

When sports teams fleece taxpayersThe Explainer Do taxpayers benefit from spending billions to subsidize sports stadiums? The data suggests otherwise.

-

The 2018 World Series is bad for baseball

The 2018 World Series is bad for baseballThe Explainer Boston and L.A.? This stinks.

-

This World Series is all about the managers

This World Series is all about the managersThe Explainer Baseball's top minds face off

-

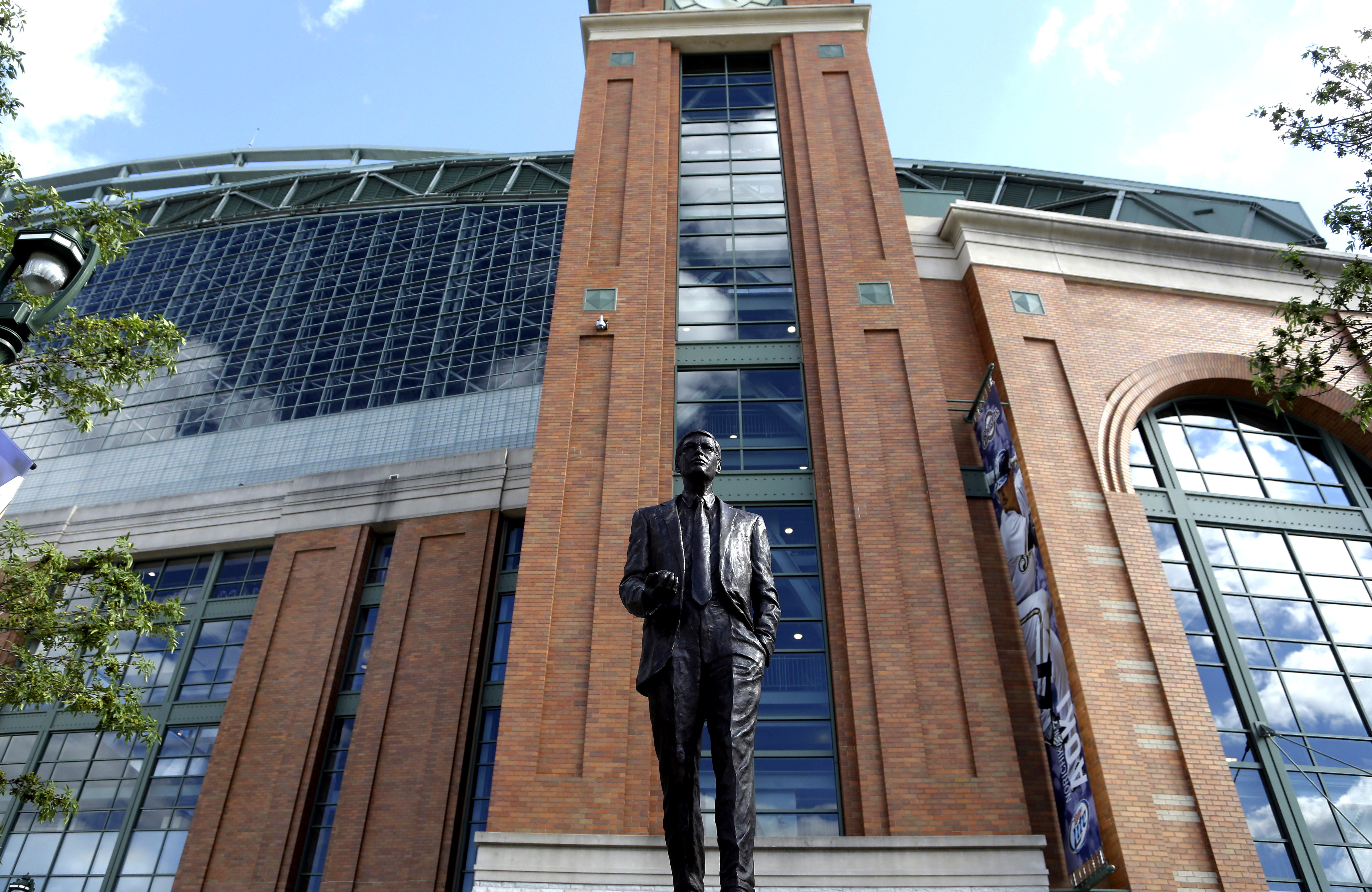

Behold, the Bud Selig experience

Behold, the Bud Selig experienceThe Explainer I visited "The Selig Experience" and all I got was this stupid 3D Bud Selig hologram