A brief history of credit cards

And how Americans fell in love with them

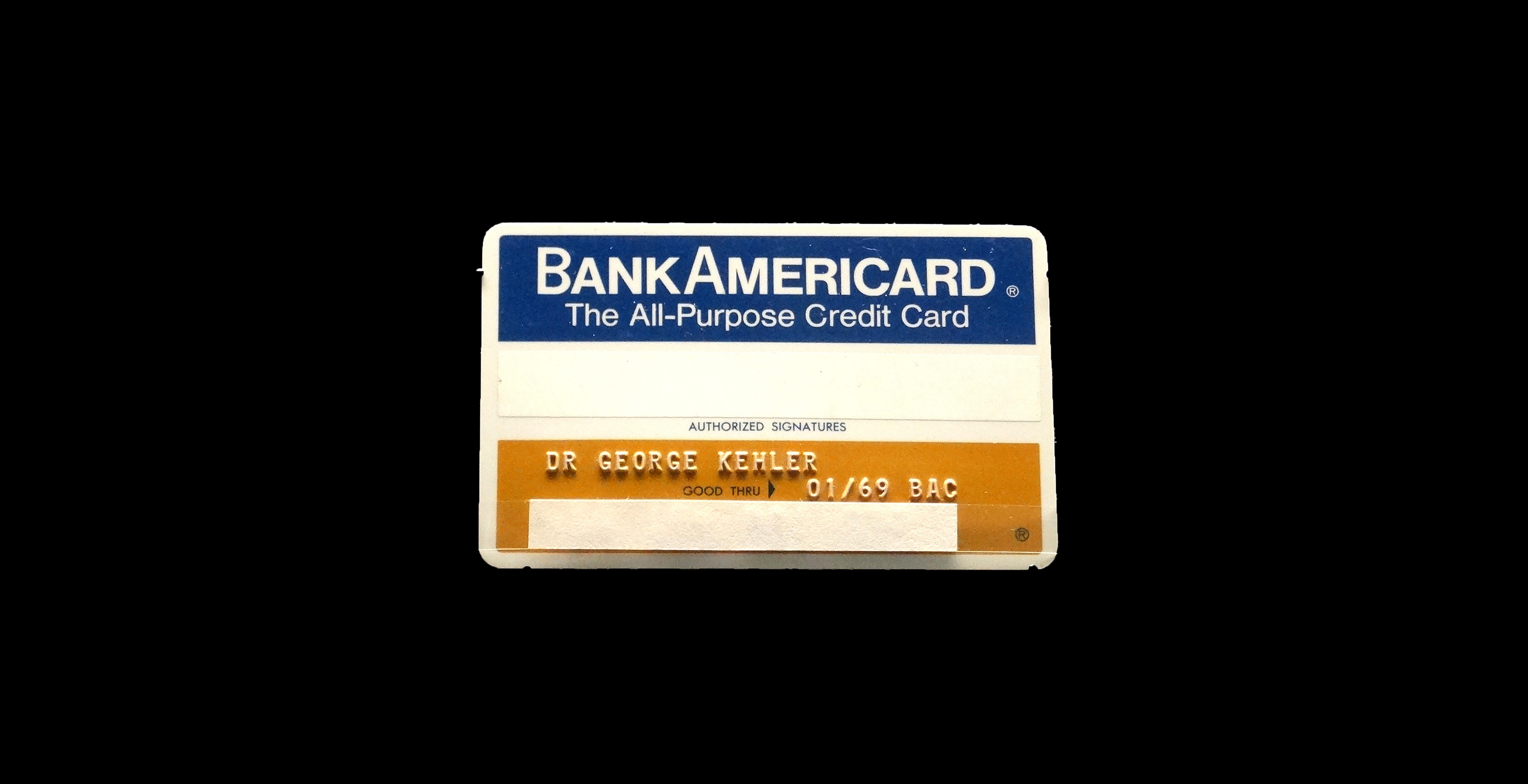

Consumer credit has always been a part of American financial life. Early Americans depended on credit extended by the local general store to float them until harvest time, when the debt would be paid off. Industrialization introduced workers to leisure time and disposable income — and they happily signed up for installment plans and department store charge cards to buy new innovations, like the sewing machine and the electric iron, that catered to the desires of this new class of consumers. But it wasn't until 1958 that America was introduced to the credit card, thanks to a middle manager at Bank of America named Joseph Williams.

Williams' thinking was that Americans were using more credit than ever, and they liked convenience. A card that offered access to a line of credit that could be used everywhere and paid off at one's leisure would be a hit. To test the market, Williams planned a rollout to communities across California, where Bank of America would drop 60,000 so-called BankAmericards into residents' mailboxes.

Williams' credit experiment backfired. It was bad. Ford Edsel bad. New Coke bad.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In the span of a year, over 2 million cards with preapproved $500 credit lines were distributed across California. But Williams' damning mistake, explained journalist Joe Nocera in his book A Piece of the Action: How the Middle Class Joined the Money Class, was that he believed that Americans were generally an honest lot and would repay their debts.

He was wrong. Williams had estimated that the default rate would be 4 percent. In reality it was 22 percent. The bank had failed to set up any kind of collections department for delinquent accounts, and fraud and card theft were rampant. The whole ordeal ended up costing Bank of America an estimated $20 million.

Not to be deterred, Bank of America tried again, introducing a national universal bank credit card in 1966. It was the first credit card that adhered to our modern definition: a line of revolving credit that could be carried month to month, used at any merchant that accepted it as payment, and available to customers at banks nationwide via a licensing agreement with Bank of America. In 1977, it was dubbed the Visa card.

This rollout, too, was underwhelming. The cards weren't profitable for banks. And "universal" was something of a misnomer, as only a limited number of merchants participated. Without a large network of retailers, it was difficult to convince people to sign up. Middle-class consumers had long become accustomed to taking advantage of installment plans for larger purchases, while department stores offered their own charge cards, payable at the end of every month, for day-to-day shopping. Travel and entertainment cards like Diner's Club and American Express had entered the market in the 1950s, but they were mostly a hit with upper-class customers or expense account businessmen, like the executives of Mad Men.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

It was a 1978 Supreme Court decision that turned the tide for the credit card industry. The case, Marquette National Bank of Minneapolis v. First of Omaha Service Corp, essentially deregulated consumer credit cards. The ruling allowed nationally chartered banks to issue plastic to customers anywhere in the country at the interest rates determined by the laws in the bank's home state. This is why most of your credit cards bills (if you still receive statements by mail, that is) come from South Dakota or Delaware. These states had no laws to limit interest rates, and banks flocked there.

The effect on the credit card industry was almost immediate. In 1970, 16 percent of U.S. families reported having a credit card. By 1983, that percentage shot up to 43 percent. Untethered from regulatory laws, credit card companies could charge interest rates that were high enough to enable them to turn a profit and inoculate them from risk, allowing access to credit to trickle down to middle- and working-class consumers, and to people with poor credit.

The timing was perfect for the credit card industry. Consumer habits were changing. The ubiquity of department stores was declining, replaced with smaller stores that catered to a specific niche, like women's clothing or kitchenware. Shoppers still loved the convenience of the store credit cards from the old-guard department stores, but smaller retailers didn't have the capacity to offer the same service. Enter the credit card.

Over the next 10 years, as wages stagnated but costs continued to rise, Americans turned to credit cards to bridge the gap between paychecks. The sheer number of Americans ready and willing to take on as much debt as possible was unlike anything seen before in U.S. history. Personal bankruptcies and personal debt exploded.

The number of people who carried a balance on their credit cards from month to month rose, while personal savings declined. With Ronald Reagan in the White House and Alan Greenspan in charge of the Federal Reserve, consumer confidence was high, and a free-market mindset assured consumers that they wouldn't spend more than they could pay back. Credit card advertisements promised that you could "sign your way around the world" and "have it the way you want it."

In the 1990s, access to credit was again expanded, this time to those truly on the financial fringe. Now, Americans with checkered financial histories could secure a line of credit with a subprime credit card. Low interest rates encouraged people to borrow more than they could afford and to stretch out repayment over longer periods of time.

By 2004, credit card defaults and personal bankruptcy filings had reached record heights, while the housing bubble pushed real estate values sky-high. Instead of saving disposable income and applying it against their credit card balance, homeowners simply took out home equity loans to pay down credit card debt. In a 2007 Federal Reserve report, Greenspan referred to this excess wealth from inflated home prices as "free cash."

Americans would soon find out, however, that "free cash" wasn't free at all.

When the recession hit, many households found themselves dangerously overleveraged. As unemployment spiked, so did the average household credit card balance. It maxed-out at $7,415.46, before beginning a multi-year decline when consumers finally began to pay down their debt. After allowing the industry to operate largely without oversight for years, Congress passed the Credit CARD Act of 2009. The bill required lenders to notify card holders of interest rate changes and to inform consumers of how long it would take to pay off a balance when only paying the minimum payment.

It's important to remember that the best interests of the credit card industry and the best interests of consumers are fundamentally opposed. Ideally, people would only charge what they could afford. They would pay off their credit card balance at the end of every month, avoiding any interest payments. This would be reflected in their high credit score, which would in turn allow them to borrow at lower interest rates. However, credit card companies have based their business model on the revolvers, or those who carry their balances from month to month, racking up interest. The most attractive customer is one who maintains a high balance and only makes the minimum payment. They are more likely to incur late penalties and are vulnerable to fluctuating interest rates.

Post-recession, this division has, for the time being, taken on a more balanced approach. Credit card issuers have shown more restraint in extending credit lines to risky borrowers, and the number of card holders who default has gone down. But it's all relative: As of January 2017, Americans still collectively held more than $1 trillion of credit card debt.

-

August 30 editorial cartoons

August 30 editorial cartoonsCartoons Saturday’s political cartoons include Volodymyr Zelenskyy and Donald Trump's role reversal and King George III

-

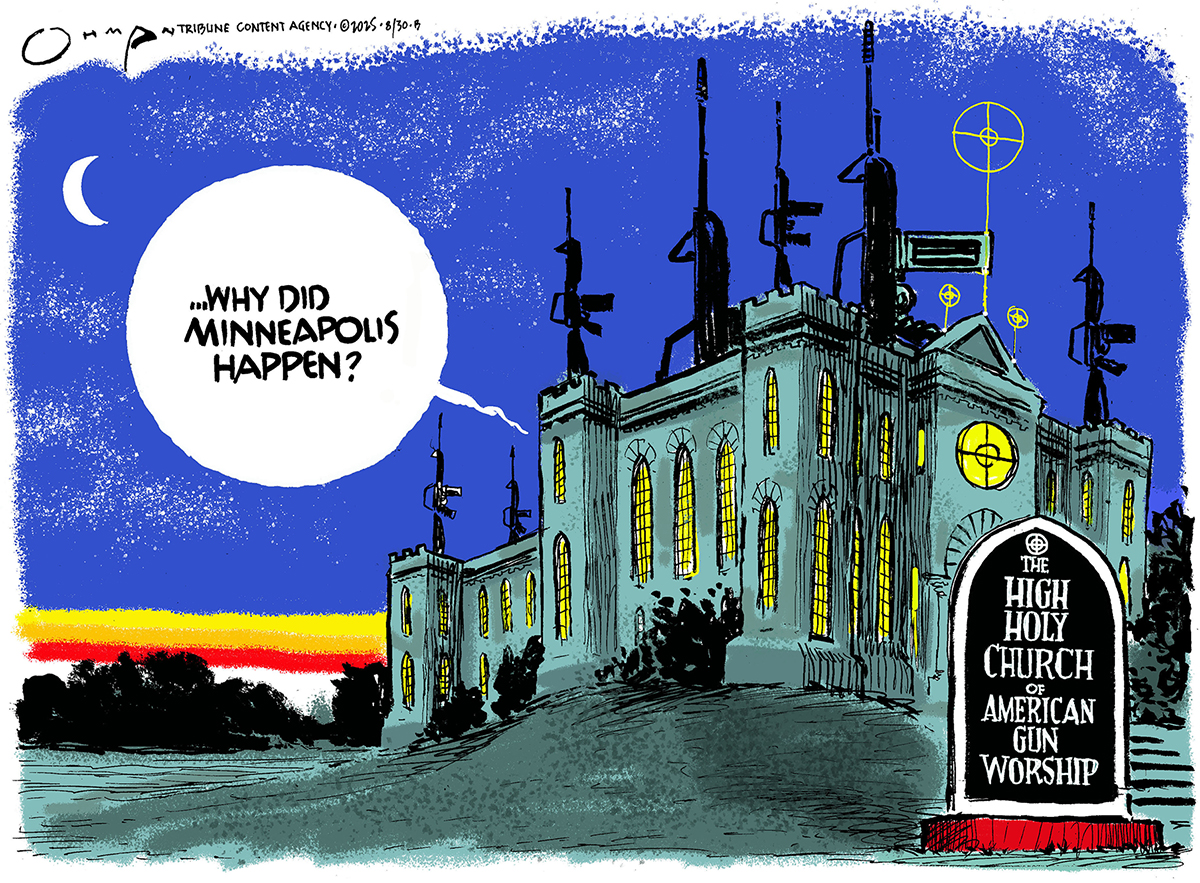

5 bullseye cartoons about the reasons for mass shootings

5 bullseye cartoons about the reasons for mass shootingsCartoons Artists take on gun worship, a price paid, and more

-

Lisa Cook and Trump's battle for control the US Fed

Lisa Cook and Trump's battle for control the US FedTalking Point The president's attempts to fire one of the Federal Reserve's seven governor is represents 'a stunning escalation' of his attacks on the US central bank

-

The pros and cons of noncompete agreements

The pros and cons of noncompete agreementsThe Explainer The FTC wants to ban companies from binding their employees with noncompete agreements. Who would this benefit, and who would it hurt?

-

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contraction

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contractionThe Explainer The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

-

The death of cities was greatly exaggerated

The death of cities was greatly exaggeratedThe Explainer Why the pandemic predictions about urban flight were wrong

-

The housing crisis is here

The housing crisis is hereThe Explainer As the pandemic takes its toll, renters face eviction even as buyers are bidding higher

-

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkers

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkersThe Explainer Show up for your colleagues by showing that you see them and their struggles

-

What the stock market knows

What the stock market knowsThe Explainer Publicly traded companies are going to wallop small businesses

-

Can the government save small businesses?

Can the government save small businesses?The Explainer Many are fighting for a fair share of the coronavirus rescue package

-

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shock

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shockThe Explainer This could be a huge problem for the entire economy