How a generation of American children grew up expecting to be shot by other children

How is it possible that something this evil — without precedent in the history of this country and with few parallels abroad, even in countries in the midst of civil war — has become more routine than elections or the Super Bowl?

In my lifetime American children being murdered at school by their fellow students has become an almost unremarkable occurrence.

How did this happen? When Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold killed 12 of their classmates and one teacher in Columbine, Colorado, it was a generation-defining moment, like the assassination of President Kennedy. It was not only the scale of the slaughter that astonished Americans who followed the story in the still early days of 24-hour cable news; it had only been a few years since the bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, killed 168 people. But the Oklahoma City bombers Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols were terrorist lunatics who looked the part. They were monstrous adults whose victims had included children, circumstances that are not exactly unknown in human history. Harris and Klebold were themselves children — awkward, misfit children with few friends to be sure, but children all the same — killing other children with cold military efficiency.

Columbine frightened everyone. Politicians, educators, parents, those of us who were students ourselves asked how this had been possible. There was a ludicrous but understandable and even touching overreaction in which any hint of violence became the object of outsized concern. I can remember having to speak with the school guidance counselor in fourth grade because my friend and I had a conversation about a character being shot in Star Wars.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

We are not living in the more innocent world of 1999. Events like Wednesday's massacre in Florida, where at least 17 people were murdered at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, are not fantastically remote contingencies. Columbine unfolded on television, but most of us saw only its aftermath. It was unthinkable for those who survived it and those who only experienced it as a media event. The bloodbath at Marjory Stoneman Douglas was live-tweeted. The students who took part in it seemed to recognize that they were participating in a familiar ritual of American life. They understood that what was happening was something called a "school shooting," an event with known conditions and procedures and conventions, something that has happened 230 times in this country since 2013. School shootings are now weekly rather than epochal events.

How, I ask once more, did this happen? How is it possible that something as evil as a school child taking the lives of several of his classmates — an event entirely without precedent in the history of this country and with few parallels abroad, even in nations in the midst of civil war — has become more routine than elections or the Super Bowl?

After Columbine we looked desperately for answers. Were Eric and Dylan inspired by the violent video games they played on their computers? We look for answers now even as we are no longer surprised. Is it that all of us, even our children, are simply more wicked than our ancestors? I cannot imagine that the portion of human evil is higher than it has ever been. We are not any worse now than we were in 1980; only grace can elevate nature, and grace is a gift given to individuals, not to citizens of entire nations. There must be something about the way our society is organized that makes us this way, something about the way in which we are able to relate to one another that does not foreclose the spectacle of mass filicide performed by children themselves as a routine, much less a possibility.

There are two parts to this riddle. One is why these slaughters have continued to occur, why, indeed, it would seem to be the case that they are becoming more frequent even as murder rates fall across the country. The other is why or how it has become possible for us to conceive of them not as hideous aberrations that defy cataloguing or description but as a genre.

Can we blame the media that sensationalizes these tragedies by broadcasting mobile phone footage of children huddled in corners screaming as gun shots echo around them? What about the internet? The obvious answer, of course, is that it is because we have so many guns. No one will have been surprised to read that the weapon believed by police to have been used at Marjory Stoneman Douglas was an AR-15, the beloved toy of millions of backyard Rambos. I am not sure that this is satisfactory, but who could deny the point? Indeed, if I had the power to confiscate every firearm now in private hands in this country, I, a proud hunter, would do so without hesitation. Lots of countries have armed citizens; only in America is the gruesome reality of firearms being discharged in 45 schools since the beginning of the year a humdrum statistic. Why? I do not think it is possible to answer the question.

I am not advocating quietism here. What I think is and should remain elusive in 2018 is not a solution, which would be welcome, but an explanation. There cannot be one. Children killing children is something that can never be countenanced, understood, rationally debated, or made the subject of philosophical speculation. It is too abhorrent.

The fact that in America children have grown up thinking of it as a televisual ceremony is, in its way, almost as gruesome as the murders themselves.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Matthew Walther is a national correspondent at The Week. His work has also appeared in First Things, The Spectator of London, The Catholic Herald, National Review, and other publications. He is currently writing a biography of the Rev. Montague Summers. He is also a Robert Novak Journalism Fellow.

-

Is Trump's tariffs plan working?

Is Trump's tariffs plan working?Today's Big Question Trump has touted 'victories', but inflation is the 'elephant in the room'

-

What are VPNs and how do they work?

What are VPNs and how do they work?The Explainer UK sees surge in use of virtual private networks after age verification comes into effect for online adult content

-

Why is it so hard to find an 'eligible' man?

Why is it so hard to find an 'eligible' man?In the Spotlight The lack of college-educated suitors is forcing women to 'marry down'

-

'Once the best in the Middle East,' Beirut hospital pleads for fuel as it faces shutdown

'Once the best in the Middle East,' Beirut hospital pleads for fuel as it faces shutdownSpeed Read

-

Israeli airstrikes kill senior Hamas figures

Israeli airstrikes kill senior Hamas figuresSpeed Read

-

An anti-vax conspiracy theory is apparently making anti-maskers consider masking up, social distancing

An anti-vax conspiracy theory is apparently making anti-maskers consider masking up, social distancingSpeed Read

-

Fighting between Israel and Hamas intensifies, with dozens dead

Fighting between Israel and Hamas intensifies, with dozens deadSpeed Read

-

United States shares 'serious concerns' with Israel over planned evictions

United States shares 'serious concerns' with Israel over planned evictionsSpeed Read

-

Police raid in Rio de Janeiro favela leaves at least 25 dead

Police raid in Rio de Janeiro favela leaves at least 25 deadSpeed Read

-

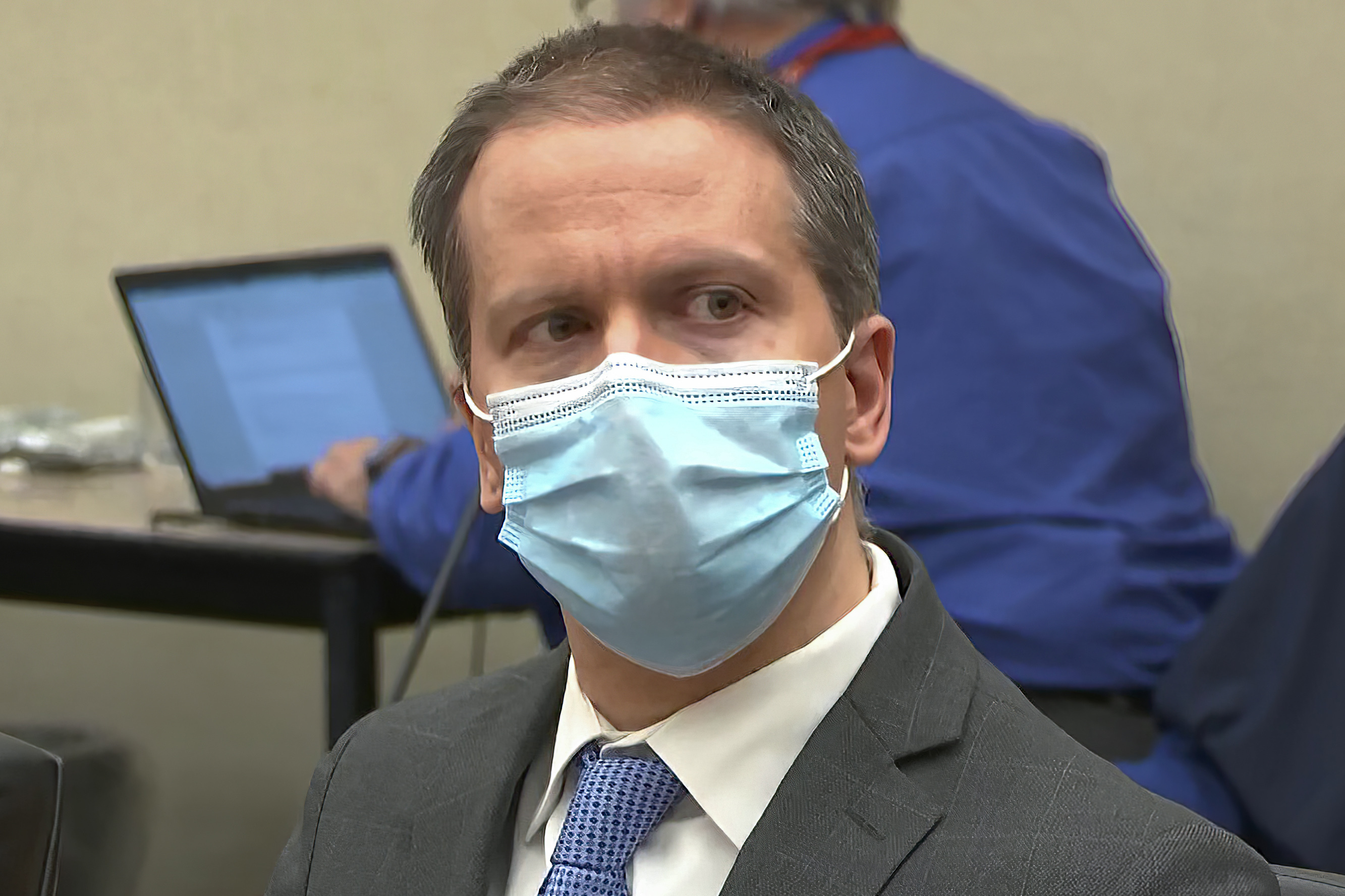

Derek Chauvin's attorney files motion for new trial

Derek Chauvin's attorney files motion for new trialSpeed Read

-

At least 20 dead after Mexico City commuter train splits in overpass collapse

At least 20 dead after Mexico City commuter train splits in overpass collapseSpeed Read