How Medicare for all could save the American health-care system

We are spending way too much on health care. It doesn't have to be this way.

The American health-care Jenga tower is getting more wobbly by the minute. To fix the problem, leftists and even many liberals have been pushing Medicare for all as a reform that would finally cover everyone in the country.

In response, people like President Trump, former Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz, and CNN's John Berman and Poppy Harlow have argued that Medicare for all is simply too expensive. "[S]ingle-payer will bankrupt our country," Trump has said. Meanwhile, just this week, House Republicans floated a plan to balance the budget by making massive cuts to social programs, Medicare included.

This is the opposite of what we should be doing. To prevent the cancerous American health-care system from devouring the entire economy, Medicare for all — or something comparably simple and aggressive — is needed, pronto.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

So what are the problems with the existing system? The ObamaCare exchanges, plagued by faulty design and Trump administration sabotage, are increasingly unstable and expensive — especially for people who make too much money to qualify for subsidies. But employer-sponsored insurance (which covers vastly more people than the exchanges) is also getting steadily worse: Every year such coverage costs more, and a greater fraction of it includes deductibles and co-pays, which are themselves getting larger.

Prices for individual procedures vary enormously within the United States, and are wildly out of line compared to international norms. It sounds almost tautologically obvious, but at the most basic level, American health care is expensive because prices are so high. In 2008, the average insurance premium for family coverage at firms with more than 200 employees was $12,973, or 26 percent of that year's median household income of $50,303. In 2017, that same premium was $19,235, or 33 percent of the median household income of about $58,500 — and that's not including co-pays, deductibles, or other cost sharing. (Comparing average premiums to median incomes is not ideal, but it's reasonable given that insurance premiums are not nearly as unequal as incomes.)

That bloated cost structure is reflected in total health-care spending, which is eating up an ever more ludicrous fraction of the economy. In 2008, health care accounted for 16.6 percent of GDP, or nearly $7,800 per person. In 2016, it was 17.2 percent of GDP, or more than $10,000 per person — which is about twice the average among the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development's 37 countries.

Greater health-care spending is not necessarily objectionable. As a country becomes more rich, it makes sense that it will dedicate more resources to medicine. A poor country might have to ration expensive treatments, where it might provide them to all when it becomes rich. That is more or less the choice that other wealthy nations have made — even half the American rate of spending is still a tremendous pile of resources.

But there is zero evidence that the United States is actually getting much of anything for all its gigantic spending. On the contrary, its health outcomes are middling to poor on most indicators, life expectancy is actually declining on average, and medical error is the third-most common cause of death — while at the same time, people are still being routinely bankrupted by medical bills due to lack of insurance, or out-of-network procedures, or even occasionally dying from lack of coverage. A number of diabetics have recently perished due to inability to afford insulin, the price of which has been driven through the roof by predatory manufacturers.

In short, America is in the ludicrous position of flinging the equivalent of the entire economic output of Indonesia (population: 260 million) at its health-care system and still people are dying for the lack of $50 worth of 100-year-old commodity medications.

American health-care costs so much not because people are getting the best treatment in the world, but because the Byzantine nightmare of its fragmented system provides endless ripoff opportunities for the unscrupulous, while simultaneously requiring a vast bureaucracy to handle the incomprehensible complexity. No other country has a nearly one-to-one correspondence between hospital beds and hospital billing staff.

Liberals predicted that ObamaCare would "bend the cost curve" through various ultra-complicated incentives and rules. Some of them sort of worked, others did not. But overall spending has continued to far outpace the rate of inflation. The simplest answer is "all-payer rate setting," otherwise known as medical price controls. Effectively, the entire Medicare price schedule (which is much cheaper than other prices, but also needs to be rationalized) would be extended to every provider. This works great in many countries — but does not solve the problem of coverage. So at that point, you might as well complete a universal Medicare system and fold everyone into it.

In a normal country, the question of whether the nation can afford a generous national health-care system is a sensible one. But America is not a normal country. We already dedicate enough resources to fund two generous medical systems — indeed, if we paid Canada's medical prices, just existing medical taxes would already be more than enough to pay for a decent Medicare-for-all system. It's simply a question of driving a big enough political brush hog through the mess of the existing system. Clear out all the policy crud, and all Americans could enjoy the world's most generous coverage — and save money to boot.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

By The Week Staff

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK

-

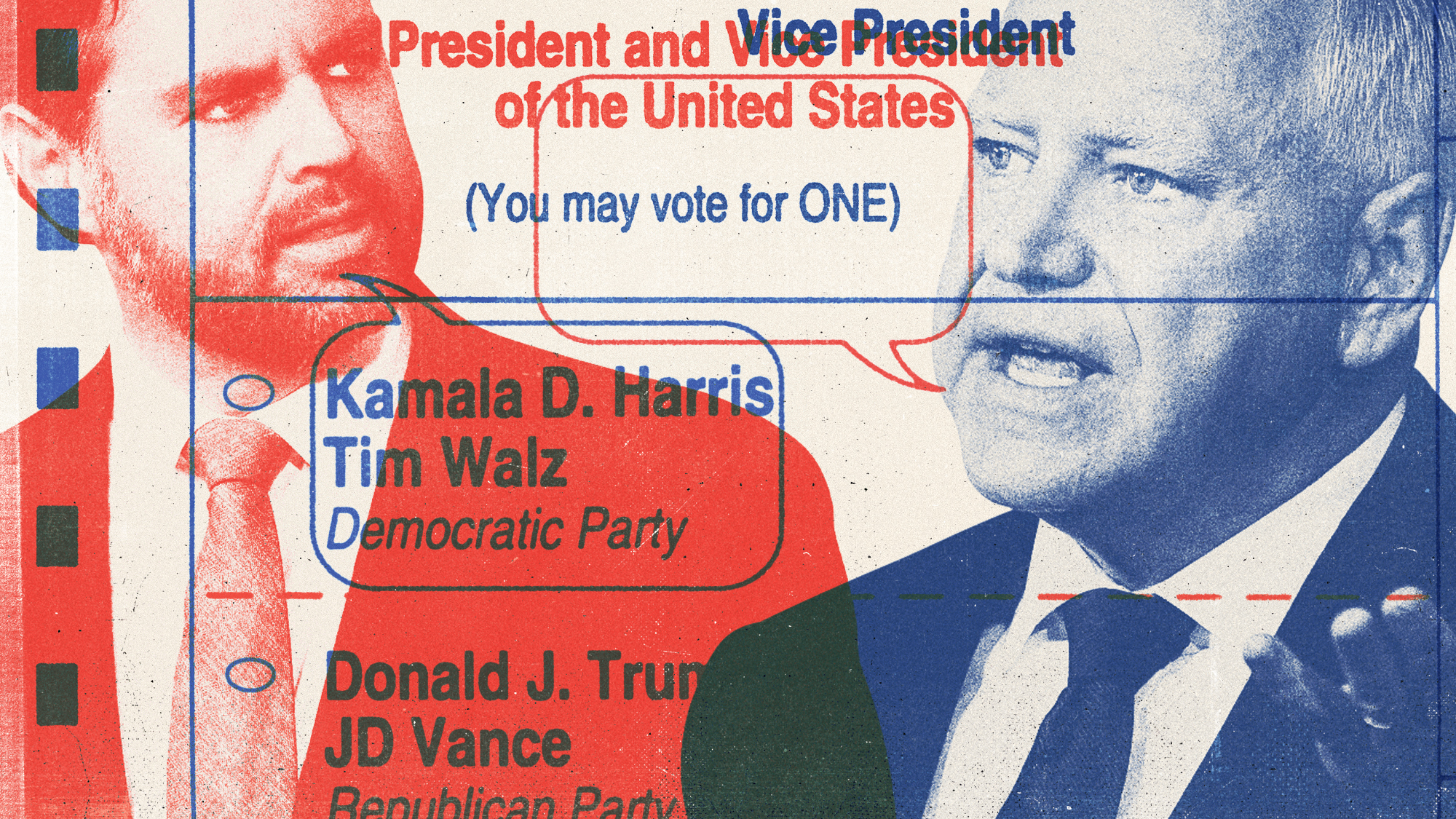

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are the billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are the billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK

-

US election: where things stand with one week to go

US election: where things stand with one week to goThe Explainer Harris' lead in the polls has been narrowing in Trump's favour, but her campaign remains 'cautiously optimistic'

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK

-

Is Trump okay?

Is Trump okay?Today's Big Question Former president's mental fitness and alleged cognitive decline firmly back in the spotlight after 'bizarre' town hall event

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK

-

The life and times of Kamala Harris

The life and times of Kamala HarrisThe Explainer The vice-president is narrowly leading the race to become the next US president. How did she get to where she is now?

By The Week UK

-

Will 'weirdly civil' VP debate move dial in US election?

Will 'weirdly civil' VP debate move dial in US election?Today's Big Question 'Diametrically opposed' candidates showed 'a lot of commonality' on some issues, but offered competing visions for America's future and democracy

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK