How student debt devoured my life

Forty-four million borrowers in the U.S. owe a total of roughly $1.4 trillion in student loan debt, with no relief from lawmakers in sight

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

On Halloween in 2008, about six weeks after Lehman Brothers collapsed, my mother called me from Michigan to tell me that my father had lost his job in the sales department of Visteon, an auto parts supplier for Ford. Two months later, my mother lost her own job working for the city of Troy, a suburb about half an hour from Detroit. From then on our lives seemed to accelerate, the terrible events compounding fast enough to elude immediate understanding. By June, my parents, unable to find any work in the state where they'd spent their entire lives, moved to New York, where my sister and I were both in school. A month later, the mortgage on my childhood home went into default for lack of payment.

In the summer of 2010, I completed school at New York University, where I received a B.A. and an M.A. in English literature, with more than $100,000 of debt, for which my father was a cosigner. By this time, my father was still unemployed and my mother had been diagnosed with an aggressive form of breast cancer. In January 2011, Chase Bank took full possession of the house in Michigan. Meanwhile, the payments for my debt — which had been borrowed from a variety of federal and private lenders, most prominently Citibank — totaled about $1,100 a month.

My parents never lived extravagantly. College, which cost roughly $50,000 a year, was the only time that money did not seem to matter. "We'll find a way to pay for it," my parents said repeatedly. Like many well-meaning but misguided baby boomers, neither of my parents received an elite education, but they nevertheless believed that an expensive school was not a materialistic waste of money; it was the key to a better life than the one they had.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Now 30 years old, I have been incapacitated by debt for a decade. The delicate balancing act my family and I perform in order to make a payment each month has become the organizing principle of our lives. I've spent a great deal of time in the last decade shifting the blame for my debt. Whose fault was it? My devoted parents, for encouraging me to attend a school they couldn't afford? The banks, which should never have lent money to people who clearly couldn't pay it back to begin with, continuously exploiting the hope of families like mine, and quick to exploit us further once that hope disappeared? Or was it my fault for not having the foresight to realize it was a mistake to spend roughly $200,000 on a school where, in order to get my degree, I kept a journal about reading Virginia Woolf?

The problem, I think, runs deeper than blame. The foundational myth of an entire generation of Americans was the false promise that education was priceless — that its value was above or beyond its cost. College was not a right or a privilege but an inevitability on the way to a meaningful adulthood. What an irony that the decisions I made about college when I was 17 have derailed such a goal.

After the dust settled on the collapse of the economy, and on my family's lives, we found ourselves in an impossible situation: We owed more each month than we could collectively pay. And so we wrote letters to Citibank's mysterious P.O. Box address in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, begging for help, letters that I doubt ever met a human being. The letters began to constitute a diary for my father in particular, a way to communicate a private anguish that he mostly bottled up, as if he were storing it for later. In one letter, addressed "Dear Citi," he pleaded for a longer-term plan with lower monthly payments. He described how my mother's mounting medical bills, as well as Chase Bank's collection on our foreclosed home, had forced the family into bankruptcy, which provided no protection in the case of private student loans. We were not asking, in the end, for relief or forgiveness, but merely to pay them an amount we could still barely afford. "This is an appeal to Citi asking you to work with us on this loan," he wrote to no one at all.

After 10 years of living with the fallout of my own decisions about my education, I have come to think of my debt as like an alcoholic relative from whom I am estranged, but who shows up to ruin happy occasions. But when I first got out of school and the reality of how much money I owed finally struck me, the debt was more of a constant and explicit preoccupation, a matter of life and death. I would look at the number on my paycheck and obsessively subtract my rent, the cost of a carton of eggs and a can of beans (my sustenance during the first lean year of this mess), and the price of a loan payment.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

At my lowest points, I began fantasizing about dying, not because I was suicidal, but because death would have meant relief from having to come up with an answer. My life, I felt, had been assigned a monetary value — I knew what I was worth, and I couldn't afford it, so all the better to cash out early.

And so it felt good to think about dying, in the way that it felt good to take a long nap in order to not be conscious for a while. These thoughts culminated in November 2010, when I met with my father one afternoon at a diner in Brooklyn to retrieve more financial paperwork. My hope for some forgiving demise had resulted in my being viciously sick for about 10 days with what turned out to be strep throat. I refused to go to the doctor in the hope that my condition might worsen into a more serious infection that, even if it didn't kill me, might force someone to at last lavish me with pity. I coughed up a not insignificant portion of yellowish fluid before my father and I entered the restaurant. We sat at a table, and I frowned at the forms he handed me. I started the conversation by asking, "Theoretically, if I were to, say, kill myself, what would happen to the debt?"

"I would have to pay it myself," my father said, in the same tone he would use a few minutes later to order eggs. He paused and then offered me a melancholy smile, which I sensed had caused him great strain. "Listen, it's just debt," he said. "No one is dying from this."

My father had suffered in the previous two years. In a matter of months, he had lost everything he had worked most of his adult life to achieve. Throughout this misery my father had reacted with what I suddenly realized was stoicism, but which I had long mistaken for indifference. This misunderstanding was due in part to my mother, whom my father mercifully hadn't lost, and who had suffered perhaps most of all. I felt a flood of sympathy for him. I was ashamed of my selfishness. The lump in my throat began to feel less infectious than lachrymal. "Okay," I said to him, and that was that. When I got home, I scheduled an appointment with a doctor.

It was in the summer of 2017, after my father, now nearing 70, had lost another job, when I finally removed him as a cosigner and refinanced my loans with one of the few companies that provides such a service, SoFi.

SoFi has not made my situation much more tenable, necessarily. The main difference is that I now write one check instead of several and I have an end date for when the debt, including the calculated interest — about $182,000 — will be paid off: 2032, when I'll be 44, a number that feels only slightly less theoretical to me than 30 did when I was 17. What I have to pay each month is still, for the most part, more than I am able to afford, and it has kept me in a state of perpetual childishness. I rely on the help of people I love and live by each paycheck. I still harbor anxiety about the bad things that could befall me should the paycheck disappear.

SoFi, which bills itself as a "modern finance company" (its name is shorthand for Social Finance, Inc.), is a Silicon Valley startup that offers, in addition to loans, membership outreach in the form of financial literacy workshops and free dinners. Their aim is to "empower our members," a mission that was called into question by the resignation, in September 2017, of its CEO, Mike Cagney, who employees allege had engaged in serial workplace sexual harassment and who ran the office, according to a New York Times headline, like "a frat house." The news of Cagney came out not long after I had refinanced my loans with the company — I became, I suppose, a SoFi'er, in the company's parlance. Around this time, I started receiving curious emails from them: "You're Invited: 2 NYC Singles Events" or "Come Celebrate Pride With Us!" "Dear NYC SoFi'er," one of these emails read, "Grab a single friend and join us for a fun night at Rare View Rooftop Bar and Lounge in Murray Hill! You'll mingle with some of our most interesting (and available!) members...."

I am a 30-year-old married man with more than $100,000 of debt, who makes less each year than what he owes. Buying a pair of pants is a major financial decision for me. I do not think myself eligible in any sense of the word, nor do I find my debt to be amusing merely on a conversational level. Still, I felt as if in 10 years the debt hadn't changed, but the world had, or at least the world's view of it. This thing, this 21st-century blight that had been the source of great ruin and sadness for my family, was now so normal — so basic — that it had been co-opted by the wellness industry of Silicon Valley. My debt was now approachable, a way to meet people.

Let's say I was morbidly intrigued. The day after Valentine's Day, I went to a Mexican restaurant in the financial district for a SoFi community dinner — this was not a singles event, but simply a free meal. Despite the name tags, the dinner turned out to resemble something more like an AA meeting, an earnest session of group therapy. They all had their story about the problems caused by their student loans and how they were trying, one day at a time, to improve things, and no story was exceptional, including my own. Ian, an employee for Google who had recently successfully paid off his debt from a Columbia MBA program, became something like my sponsor for the evening. He said he'd had a few "bone dry" years, when he'd lived on instant noodles. I told him I had a long way to go. "At least you're doing something about it," he said, sincerely.

We sat down to dinner. Across from me was Mira, a defense attorney from Brooklyn, who attended law school at Stanford University. Her payments amount to $2,300 a month, more than double my own. When I asked her why she'd come to this event, she glanced at me as if the answer should have been obvious: She went to law school at Stanford, and her payments are $2,300 a month. The table, myself included, looked on her with an odd reverence. She wore a business suit and had her hair pulled back, but I saw her as something like the sage and weathered biker of the group, holding her 20-year chip, talking in her wisdom about accepting the things you cannot change.

After the food was served, a waiter came by with a stack of to-go boxes, which sat on the edge of the table untouched for a while as everyone cautiously eyed them. The group was reluctant at first, but then Ian said, "The chicken was actually pretty good," as he scooped it into one of the boxes. Mira shrugged, took a fork, and added, "This is a little tacky, but I'd hate to waste free food," and the rest of the table followed her lead. Maybe the next generation would do better, but I felt like we were broke and broken. No number of degrees or professional successes would put us back together again. For now, though, we knew where our next meal was coming from.

Excerpted from an essay that originally appeared in The Baffler. Reprinted with permission.

-

El Paso airspace closure tied to FAA-Pentagon standoff

El Paso airspace closure tied to FAA-Pentagon standoffSpeed Read The closure in the Texas border city stemmed from disagreements between the Federal Aviation Administration and Pentagon officials over drone-related tests

-

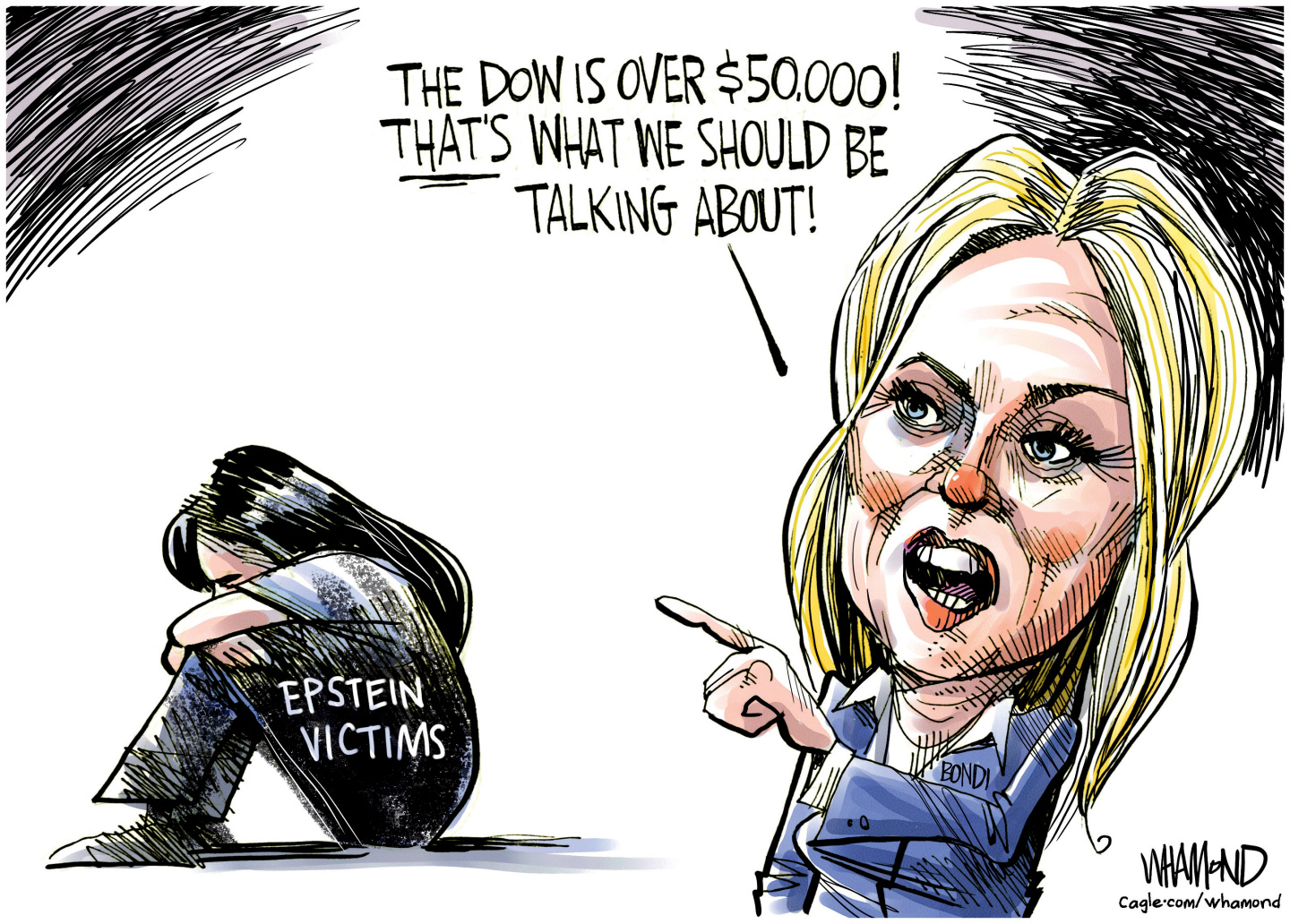

Political cartoons for February 12

Political cartoons for February 12Cartoons Thursday's political cartoons include a Pam Bondi performance, Ghislaine Maxwell on tour, and ICE detention facilities

-

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ return

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ returnThe Week Recommends Carrie Cracknell’s revival at the Old Vic ‘grips like a thriller’