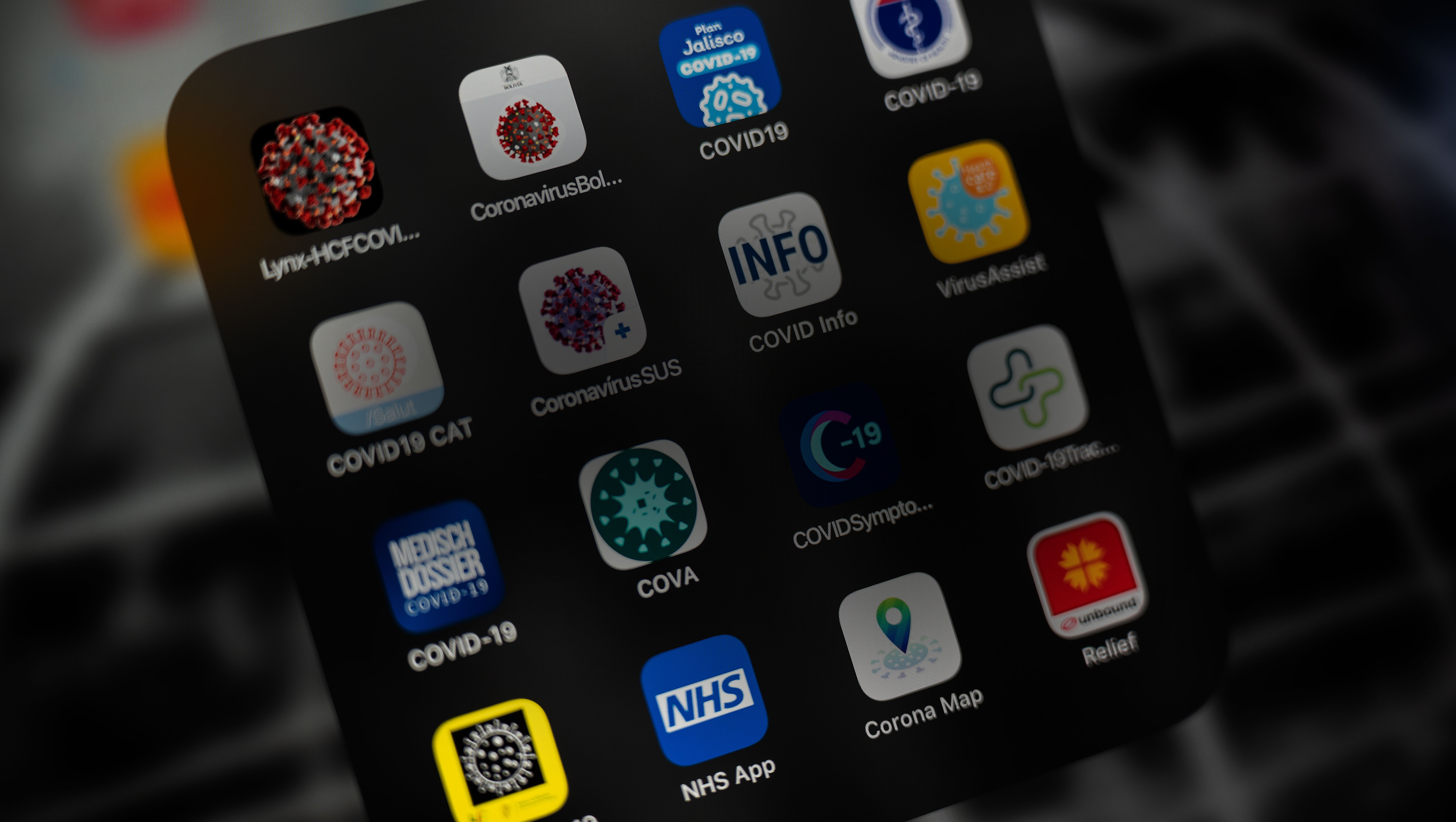

Coronavirus: do Covid-19 tracking apps work?

The promise that technology would deliver us from the pandemic has not yet been fulfilled

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

As the government prepares to launch its ill-fated coronavirus app, other European countries are beginning to publish information about how their apps are performing.

They have “achieved some early successes”, says Reuters. “Millions of people have downloaded smartphone tracker apps and hundreds have uploaded the results of positive Covid-19 tests.”

Yet most countries “lack solid evidence” that their apps are helping to contain the virus.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Part of the problem is that neither governments nor the public can find out who is receiving alerts about potential infection. In most cases, even how many notifications the apps are generating remains unknown.

“The privacy-conscious way in which they are designed could mean we will never know how effective they have been,” the BBC reports.

In Germany, 16 million people have downloaded the country’s corona-tracking app, about 20% of the population, but only 1,052 people have requested the code they need to tell the app they have tested positive.

That represents about 150 people per week since launch, at a time when Germany is recording more than 5,000 new cases of the virus per week.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Public health experts have “limited expectations” of the app, says the British Medical Journal, and are instead focusing their efforts on a manual contact-tracing system that has been widely praised.

Not everywhere is flying quite so blind. In Ireland, which is a “bit less privacy-obsessed”, says The New York Times, the Covid app “tallies how many people upload a positive test result and how many get notifications”.

But only 58 users entered positive tests into the app - about 14% of people who tested positive. That’s well below the performance levels thought to be needed to contain the virus.

Even if everyone used the apps and all positive tests were recorded, doubts remain about whether phones can effectively record potentially infectious contacts.

“We do not know whether the software is performing its key function,” says the BBC. “Studies have indicated that Bluetooth is an unreliable way to determine the distance between two people in some common situations.”

This was one of the reasons the UK government pulled the plug on its app in June. A revised app - which may not even attempt to track contacts - is expected later this month.

Outside Europe, experience has been equally mixed. In Australia, the app proved “barely relevant”, says The Guardian. In its first month, “just one person [was] reported to have been identified using data from it”.

South Korea is the stand-out example of success, but its app is part of a far more comprehensive system that logs “extraordinarily detailed information about every infected individual, including their exact movements around the country”, says Foreign Policy.

Instead of Bluetooth, it uses GPS and the mobile phone network to track people’s locations, cross-checking that data with credit card payments, face-recognition systems and CCTV - and then uploading it to a central database.

“It’s hard to imagine many Western countries taking such a cavalier approach to patient privacy,” says the magazine. “But the app seems to be popular in South Korea.”

Holden Frith is The Week’s digital director. He also makes regular appearances on “The Week Unwrapped”, speaking about subjects as diverse as vaccine development and bionic bomb-sniffing locusts. He joined The Week in 2013, spending five years editing the magazine’s website. Before that, he was deputy digital editor at The Sunday Times. He has also been TheTimes.co.uk’s technology editor and the launch editor of Wired magazine’s UK website. Holden has worked in journalism for nearly two decades, having started his professional career while completing an English literature degree at Cambridge University. He followed that with a master’s degree in journalism from Northwestern University in Chicago. A keen photographer, he also writes travel features whenever he gets the chance.