What makes a non-starter candidate run for office?

They have almost no path to victory, so why are so many darker-than-dark-horse candidates jumping into the 2024 presidential race?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

There are few things Americans like more than underdogs; in sports, entertainment, and yes, even politics (which increasingly has come to resemble the above) there is a particular hunger for watching people struggle against — and occasionally surmount — the odds so perniciously stacked against them. Sometimes, however, an underdog is simply too far under to publicly register as a viable contender. In politics, particularly during presidential elections, these darker-than-dark horse candidates often earn outsized media attention at the onset, far beyond their presumptive limited-to-the-point-of-virtual-impossibility chances of actually being voted into office.

This year, as in years past, the roster of declared presidential candidates ranges from dominating front-runners to insurgent hopefuls to gadfly outsiders jostling to find a lane that leads them to, and through, the nominating convention. While there are certainly candidates who face an uphill battle to secure their party's support ahead of the general election, a number of declared presidential aspirants have done so in defiance of essentially all quantifiable indicators of success; professor and public intellectual Cornel West recently announced his candidacy on the progressive People's Party ticket, despite the group having no ballot access nationwide; right-wing commentator Larry Elder promised "a new American Golden Age" when he declared in late April, but has entered the race with negligible cash on hand leftover from his "Elder for America" PAC and virtually no significant campaign events to date; new age author and 2020 democratic candidate Marianne Williamson's 2024 bid has been criticized as a "vanity campaign" and "something that's not real" by former staffers, after multiple top advisors left in recent months; businessman Perry Johnson, former Cranston, Rhode Island, mayor Steve Laffey, and onetime Montana Secretary of State (and part-time country music singer) Corey Stapleton are all running for the 2024 GOP nomination as well, although the average voter would be easily forgiven for not knowing they exist at all.

Why do so many people go through the very real trouble of running for president when their campaigns' inevitable failure seems like fait accompli? Sometimes the desire to be president and the decision to run for president are motivated by very different impulses.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

To make — or simply be — a statement

For some political aspirants, the campaign is less about the electoral destination, than it is the proclamatory journey along the way. Understanding that victory is essentially a non-starter, candidates may run to "try to get my message out there and have fun with it and see what happens," explained 2022 Utah Libertarian Senate candidate James Hansen. The mere act of running in and of itself can be a way to inspire others to "get involved" and "take a bigger role" in politics.

A quixotic campaign can show the public that "there are choices" if they "have some input and speak up," agreed California business owner Charlotte Ann Hilgeman, after inviting gubernatorial candidate Joseph Brouillette to speak at a Sterling City council meeting in spite of his admission that he can't win his race.

Sometimes, fielding a candidate in an unwinnable race is not even about the candidate at all. Instead, there can be an "expectation that if a party was going to be a credible contender for government or to be taken seriously, they had to field candidates in every single district," Canadian Political Scientist Melanee Thomas said. That same sentiment of fielding candidates as a statement of party strength — or at least a sign of oppositional defiance — is alive and well in the United States; although Democrat Marcus Flowers had virtually no shot of toppling Republican Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene in 2022 considering her whopping 75-point-blowout two years earlier, "it's important that we tell Marjorie Taylor Greene that not everyone likes her," one Flowers supporter explained, adding, "I get to make a statement."

To pressure other candidates

Candidates may also opt to enter a race they have little hope of winning to force more viable candidates to speak to a broader range of issues, or assume a position they'd previously avoided. Quixotic candidates "put more pressure on so-called establishment candidates to address issues that have not necessarily been at the forefront of their policy agenda," Hofstra University political scientist Dr. Meenekshi Bose said.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

By prompting more viable candidates "to address a broader range of concerns they may not have otherwise," these dark horse candidates force "nominees to take into account the range of voices in their constituencies." Even after his personal presidential aspirations had faded in 2020, Vermont democratic socialist Sen. Bernie Sanders' presence in the primary race was a crucial factor in eventual winner Joe Biden's pivot leftward, while perennially unsuccessful New York candidate Jimmy McMillan has succeeded in turning his "rent is too damn high" platform (also the name of his self-founded political party) into a broader cultural meme, ossifying the issue in the minds of voters, regardless of his numerous campaign losses.

To earn a reputation — and money — for the future

For some candidates, losing a race is not the end of their political career — in fact, it's just the beginning. Candidates are often able to parlay a surprisingly good showing in an impossible-to-win situation into a springboard for future, more viable races, or political roles in their onetime adversaries' administrations; despite dropping out of the 2020 race with an anemic 21 delegates total, former South Bend, Indiana, mayor Pete Buttigieg's strong debate performances helped catapult him from municipal figure to high ranking cabinet official in President Biden's administration.

Candidates who have proven themselves to be prolific fundraisers — in the case of many high-profile democrats, often to a degree that's at odds with their virtually nonexistent paths to electoral victory — can also use their unspent campaign funds to amass political clout, either by doling out leftover money to other candidates or groups, or keeping it on hand to gain a leg up for their own future race. A loss, even in the case of a never-could-win situation, can still provide a candidate with the means to better position themselves for other races in the future. For example, FEC filings show that Flowers, who ultimately lost to Taylor Greene by 30 points in the 2022 midterms, has since pivoted his Marcus for Georgia campaign structure to help launch Mission Democracy, a political organization that aims to "remove MAGA extremists from Congress and stop fascism in its tracks."

To play spoiler

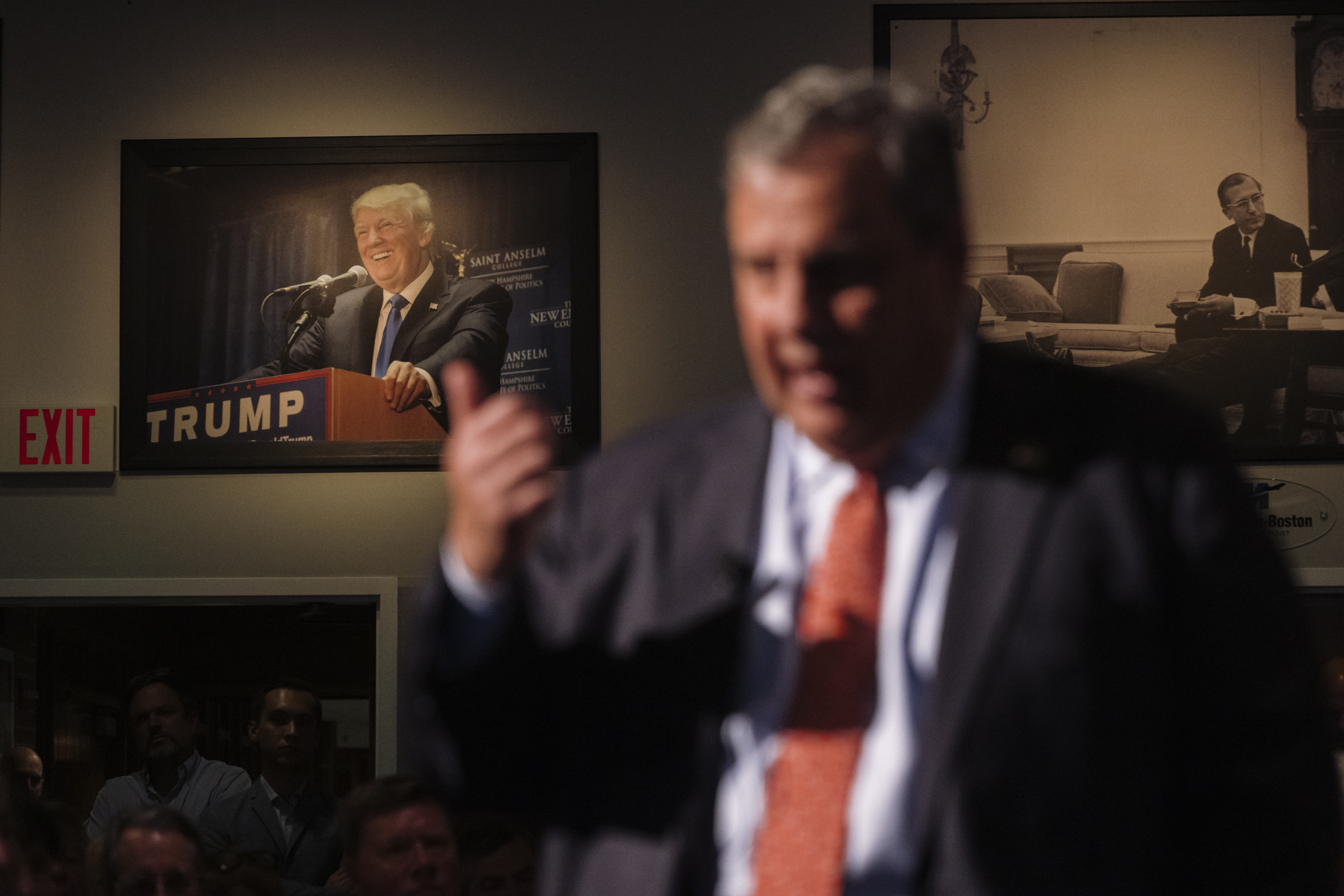

When former New Jersey Governor and erstwhile Donald Trump sycophant Chris Christie launched his second official bid for the White House in early June, he did so by taking unambiguous aim at his former political benefactor, calling Trump a "lonely, self-consumed mirror hog" in an attempt to claim the narrow anti-Trump lane in the GOP primary race. While "even some of his fiercest allies must squint to see [Christie's campaign] ending in the White House," the New York Times' Shane Goldmarcher said, Christie has also made explicit that he is running to remove Trump from contention in 2024, and from the GOP at large. Yes, he wants to become president himself, but "he's driven in equal measure by a desire to see Trump lose," said MSNBC columnist Steve Benen.

Some spoiler candidates — running with the clear understanding that their job is to siphon votes, not win — have been less forthcoming about their roles: shortly before his 2020 death, Minnesota Legal Marijuana Now Party candidate Adam Weeks confided to a friend that he'd been actively recruited by state GOP operatives to "pull votes away" from eventual winner Democrat Angie Craig. Two years later, state Democrats accused Paula Overby, the LMN's 2022 candidate in that same district of similar GOP collusion — a charge Overby denied. In 2021, former Florida State Senator Frank Artiles was arrested and charged with helping prop up a spoiler candidate tasked with drawing off voters for Democrat incumbent Jose Javier Rodriguez, who subsequently lost his bid for reelection.

Ultimately, every candidate who enters a race must, on some level, want to win their election — even if their reasons for doing so are complicated and varied. And sometimes, candidates thought to be long-to-the-point-of-impossibility shots do actually prevail against overwhelming odds. But winning, as the saying goes, isn't everything. Sometimes candidates who know they have no chance at victory still run. And sometimes that's enough.

Rafi Schwartz has worked as a politics writer at The Week since 2022, where he covers elections, Congress and the White House. He was previously a contributing writer with Mic focusing largely on politics, a senior writer with Splinter News, a staff writer for Fusion's news lab, and the managing editor of Heeb Magazine, a Jewish life and culture publication. Rafi's work has appeared in Rolling Stone, GOOD and The Forward, among others.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

How are Democrats turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonade?

How are Democrats turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonade?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION As the Trump administration continues to try — and fail — at indicting its political enemies, Democratic lawmakers have begun seizing the moment for themselves

-

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffs

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffsSpeed Read Six Republicans joined with Democrats to repeal the president’s tariffs

-

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?Today’s Big Question Democratic leadership has put forth several demands for the agency

-

Democrats push for ICE accountability

Democrats push for ICE accountabilityFeature U.S. citizens shot and violently detained by immigration agents testify at Capitol Hill hearing

-

Democrats win House race, flip Texas Senate seat

Democrats win House race, flip Texas Senate seatSpeed Read Christian Menefee won the special election for an open House seat in the Houston area

-

Is Alex Pretti shooting a turning point for Trump?

Is Alex Pretti shooting a turning point for Trump?Today’s Big Question Death of nurse at the hands of Ice officers could be ‘crucial’ moment for America

-

‘Dark woke’: what it means and how it might help Democrats

‘Dark woke’: what it means and how it might help DemocratsThe Explainer Some Democrats are embracing crasser rhetoric, respectability be damned