52 ideas that changed the world: 28. Retirement

Being able to stop work and enjoy old age has created a whole new class of citizens

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In this series, The Week looks at the ideas and innovations that permanently changed the way we see the world. This week, the spotlight is on retirement:

Retirement in 60 seconds

Retirement is the practice of leaving employment at a certain age later in life and no longer working for a living. Other reasons for retirement include sickness, an accident or deciding to leave the workforce because you are financially stable and can afford not to work.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Some people choose to semi-retire, meaning they step back from working a full-time job, but still work some hours. According to usnews.com, the advantages of semi-retirement include being able to concentrate on a social life, keeping active and generating an income after stopping full-time employment.

According to Havard Health, there is mixed evidence about whether retirement is good or bad for your health. Research has found that retirees are “40% more likely to have had a heart attack or stroke than those who were still working”, however the medical publisher also notes that there is also evidence that a reduction in work is good for people’s long-term health.

The concept of retirement has been around since around the 18th century, but as a government policy it began to be adopted by countries during the late 19th century and the 20th century.

How did it develop?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Before 1800 life expectancy in the UK was below 40 years, and the world average was less than 30 years. This meant that most people did not leave the workforce because of old age or physical impairments; they simply passed away.

The closest echoes of what we would now recognise as retirement originated in Ancient Rome, where the Roman army paid a pension to those who did military service. The New York Times also reports that the Puritan movement spoke about removing older people from the workforce, with 18th-century author and minister Cotton Mather saying that older people should be “pleased with the retirement which you are dismissed into”.

In the mid-1800s, American government employees – such as firefighters, police and teachers – began receiving a pension allowing them the financial independence to retire. This inspired the American Express Company to launch the first private pension in 1875.

However, the biggest leap forward in the development of modern retirement came in 1883, on the other side of the Atlantic.

In an effort to stave off the popularity of Marxism in Germany, Chancellor Otto von Bismarck announced that people over the age of 65 could stop working and be paid a pension. In an 1881 letter proposing the policy sent to the German Reichstag, German Emperor, William I, wrote: “Those who are disabled from work by age and invalidity have a well-grounded claim to care from the state.”

The introduction of a retirement age and pension saw Bismarck labelled a “socialist”, a charge that he rebutted. “Call it socialism or whatever you like. It is the same to me.”

Eight years after Bismarck’s original proposal, the German government had created a retirement system that provided for citizens over the age of 70. Participation in the retirement scheme was non-voluntary, and included contributions from individuals, their employer and the state.

Retirement grew in popularity after the industrial revolution, however its development in the US was stalled by the Great Depression. As the New York Times reports, the collapse of the American economy left many workers without the funds to retire. “Retirement was a necessary adaptation and everybody knew it, but the old guys were not going quietly”, journalist Mary-Lou Weisman writes.

The idea that older people would quit working for money if they were paid enough to do so was becoming widespread. In 1933 Francis Townsend, a Californian doctor, proposed a plan offering compulsory retirement at age 60. In return, individuals would be paid benefits of up to $200 a month.

The plan became known as The Townsend Plan and led to President Franklin D. Roosevelt introducing the Social Security Act of 1935. According to history.com, the act enshrined in law an old-age plan that, at Roosevelt’s insistence, would be funded by individual contributions from workers.

The old-age pension has a far longer history in the UK, having been introduced to facilitate retirement as part of Liberal chancellor David Lloyd George’s People’s Budget of 1909. The pension meant that people over the age of 70 would be paid five shillings a week (around £14 in today’s money). At the time, the average life expectancy was 47, according to The Daily Telegraph.

In Asian countries, modern retirement laws closely match that of Western countries. However, historically, the region has seen older people treated with greater respect and with less expectation of them working. “Individuals are relieved of the burden of labouring in economic production, yet ideally there are no decrements in their status, prestige, or influence within the family and community,” report the authors of Cross-cultural perspectives on the concept of retirement.

In 1951, American technology giant Corning investigated why retirement was not as popular in the West. During that roundtable discussion, Indian-born American writer and researcher on Eastern culture, Santha Rama Rau, noted that “Americans did not have the capacity to enjoy doing nothing”. According to Mental Health Foundation figures, one in five of present-day retirees experiences depression relating to loneliness, physical illness or lack of self-worth.

However, retirement communities, which first emerged in the 1920s and 30s across Western countries, have contributed to alleviating this issue. The explosion of golf courses, and the growth of films and TV, have also transformed having nothing to do into a leisure activity.

Whole areas are now synonymous with retirees, for example Florida in the United States or the Algarve in Portugal. Further afield, many Western retirees also head to Asian countries such as Thailand, in order to take advantage of the lower cost of living.

How did it change the world?

Before the widespread acceptance of a retirement age, people merely worked until they died, never stopping because of old age or ill health. As the New York Times notes, prior to retirement, “when a patriarch could no longer farm, herd cattle or pitch a tent, he opted for more specialised, less labour-intensive work”.

Retirement has created a new class of citizens, sometimes referred to as “senior citizens” in the US, with disposable income and time to enjoy their old age. A period of life that was once feared has become something some people even look forward to.

However, retirement also has its drawbacks. Research from the Institute of Economic Affairs suggests that while retirement may initially benefit health – by reducing stress and creating time for other activities – adverse effects increase the longer retirement goes on. These can include depression and isolation.

Also, as people live longer and the welfare state in many countries struggles to keep up with demand, The Guardian has reported that we are “entering the age of no retirement”, in which “those of pensionable age… cannot afford to retire, but cannot continue working”.

Joe Evans is the world news editor at TheWeek.co.uk. He joined the team in 2019 and held roles including deputy news editor and acting news editor before moving into his current position in early 2021. He is a regular panellist on The Week Unwrapped podcast, discussing politics and foreign affairs.

Before joining The Week, he worked as a freelance journalist covering the UK and Ireland for German newspapers and magazines. A series of features on Brexit and the Irish border got him nominated for the Hostwriter Prize in 2019. Prior to settling down in London, he lived and worked in Cambodia, where he ran communications for a non-governmental organisation and worked as a journalist covering Southeast Asia. He has a master’s degree in journalism from City, University of London, and before that studied English Literature at the University of Manchester.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

52 ideas that changed the world - 52. Zero

52 ideas that changed the world - 52. ZeroIn Depth The technology on which you’re reading this article only works because of zero

-

52 ideas that changed the world - 50. Money

52 ideas that changed the world - 50. MoneyIn Depth Millennia of civilisations have used mediums of exchange ranging from seashells and cows to bitcoin and cash

-

52 ideas that changed the world - 49. Ecology

52 ideas that changed the world - 49. EcologyIn Depth Scientific ecology can be traced back to Charles Darwin and considers living things and their environment

-

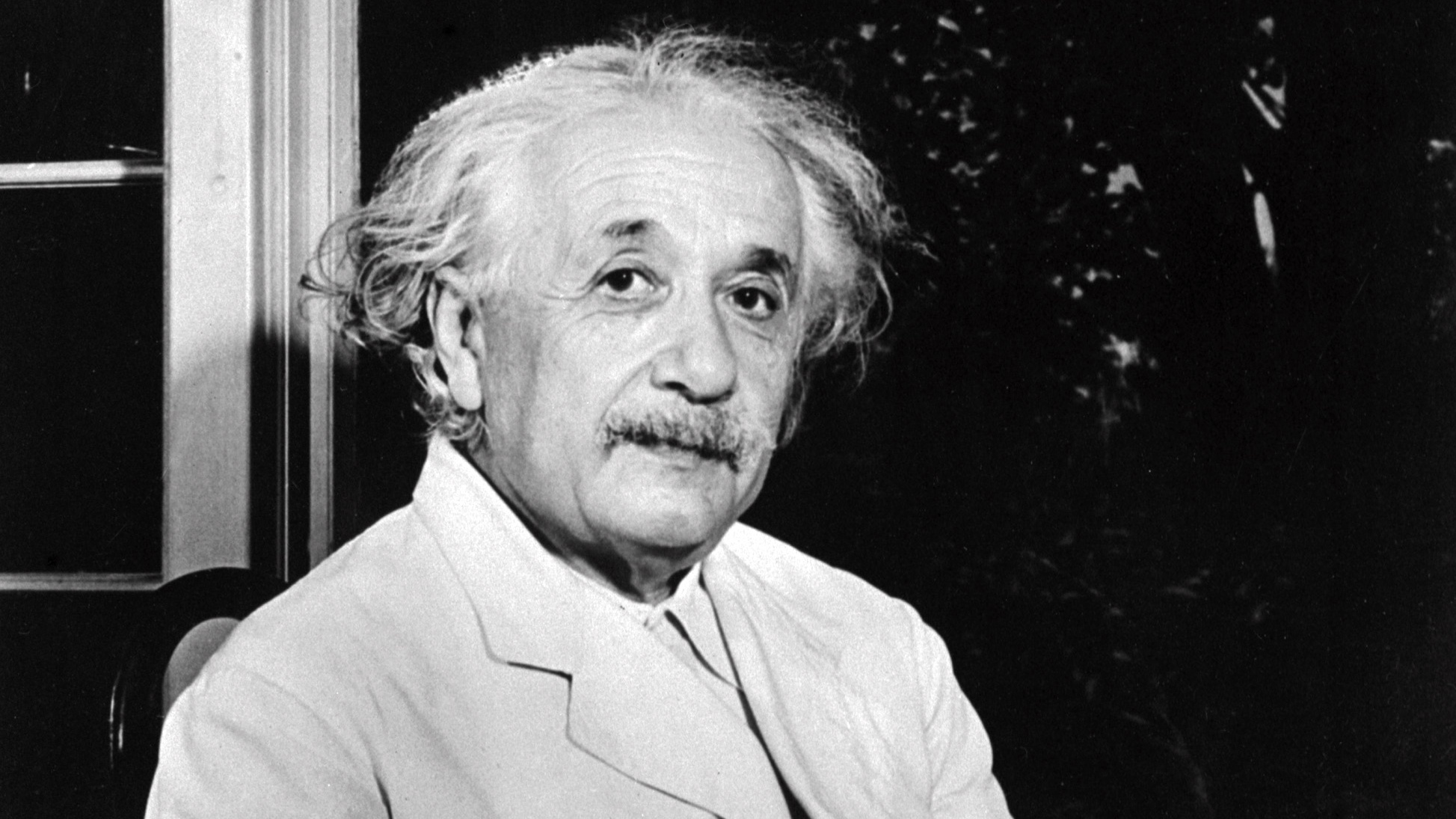

52 ideas that changed the world - 47. Relativity

52 ideas that changed the world - 47. RelativityIn Depth Einstein’s theory remains ‘most important in modern physics’

-

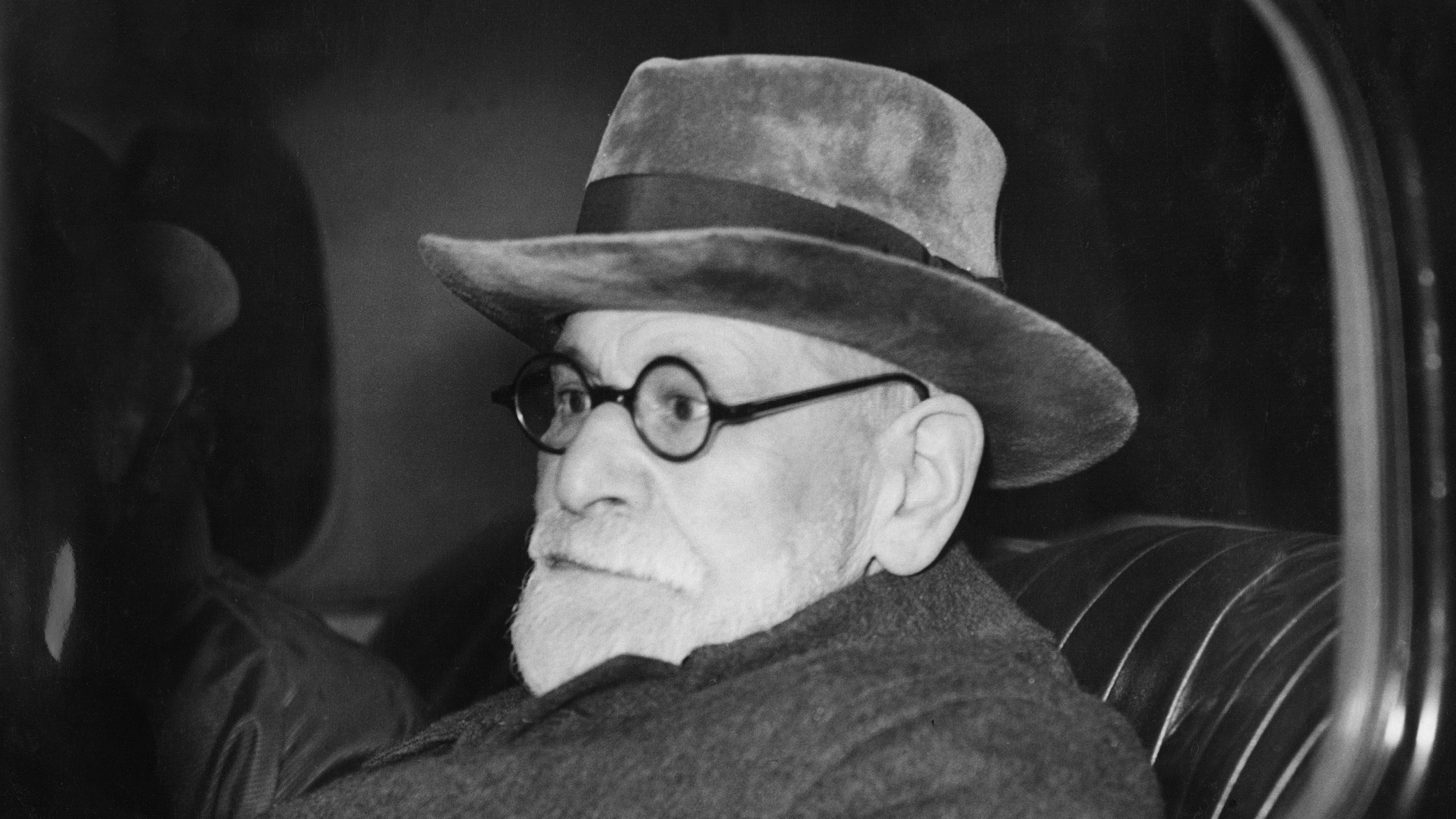

52 ideas that changed the world - 46. The unconscious mind

52 ideas that changed the world - 46. The unconscious mindIn Depth The theory of an obscured section of human consciousness has hooked psychologists for centuries

-

52 ideas that changed the world - 43. Writing

52 ideas that changed the world - 43. WritingIn Depth Writing is the foundation of history, great literature – and this article

-

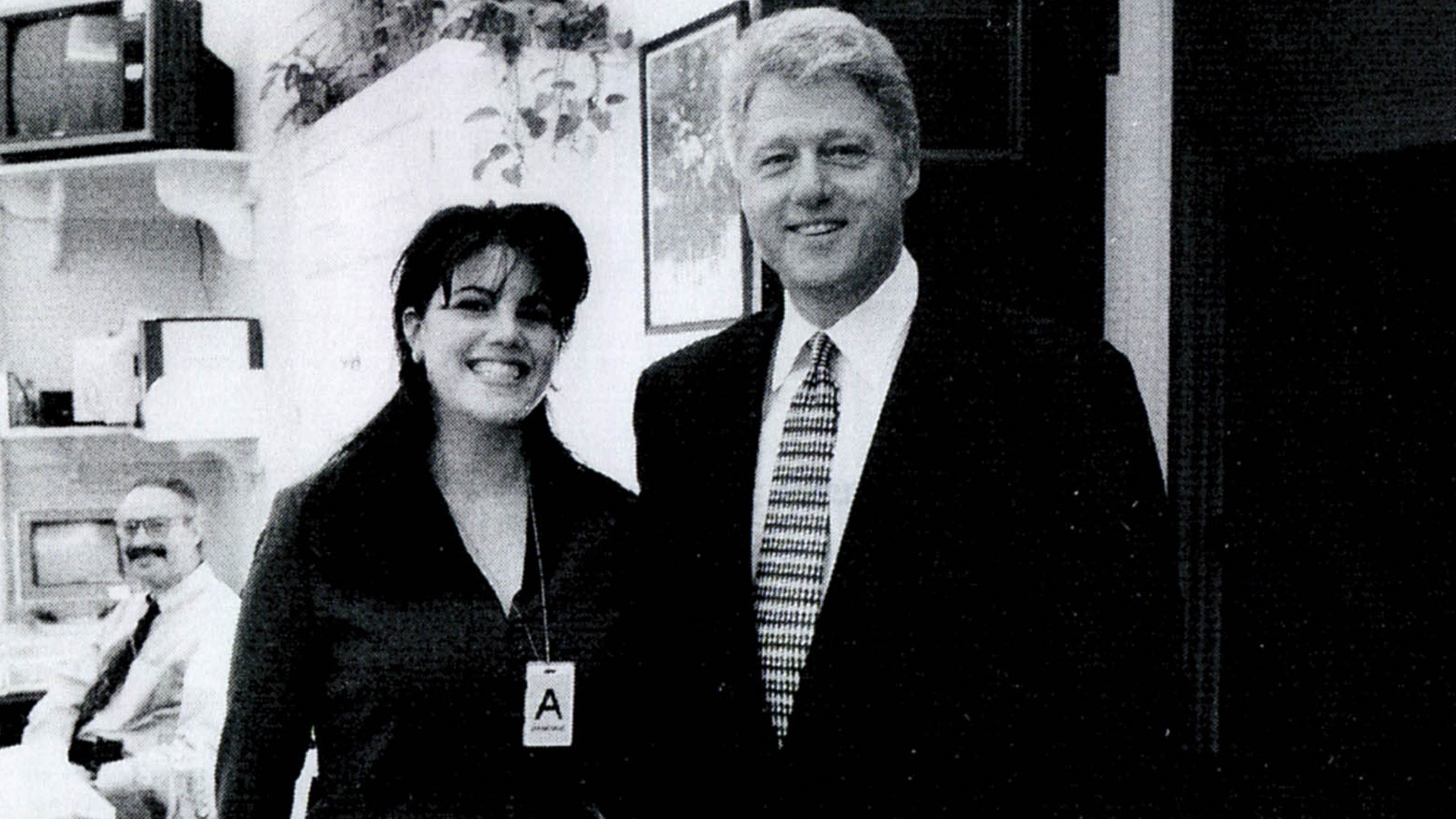

52 ideas that changed the world - 42. Monogamy

52 ideas that changed the world - 42. MonogamyIn Depth The roots of monogamy have more to do with evolution than romance

-

52 ideas that changed the world - 41. The wheel

52 ideas that changed the world - 41. The wheelIn Depth The wheel might seem simple, but it took humans a long time to figure it out