Thomas Heatherwick on his passion for public design

The award-winning architect Thomas Heatherwick tells Amy Raphael about his enthusiasm for bringing delight to public spaces

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In the seven years that Thomas Heatherwick spent in further education, which included a two-year masters in architecture and design at the Royal College of Art, he studied origami, timber joinery and embroidery. This may sound whimsical, but in fact it’s the opposite. He knew exactly what he was doing.

In the introduction to Making – a beautiful and joyous monograph detailing the stories of such high-profile projects as the hybrid-energy Routemaster bus and the Olympic Cauldron – made of 204 copper pieces to symbolise each country that took part in the 2012 Games – the designer explains his ethos further. Working with a variety of materials and processes gave him an understanding of the built environment; he considered architecture, embroidery and furniture design part of a single discipline.

Heatherwick, now 46, is one of the most gifted designers of his generation. Two years ago, Heatherwick Studio celebrated its 20th year; it was established in the same year he became the youngest practitioner to be appointed a Royal Designer for Industry.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The accolades bestowed upon him are numerous, and yet Heatherwick remains softly spoken and thoughtful when he recalls how tricky it was setting up his studio two decades ago. ‘It took many years to be trusted at the scale my brain was thinking. Why would anyone trust someone in their early twenties with projects worth millions of pounds? Now we have a reputation and we’re trusted with four-million-square-feet projects.’

His passion has always been public design, but – unbelievably, really – 20 years ago, large-scale public design projects weren’t on offer. ‘If you did something that had any aesthetic qualities, people would call it art. I’m not trained as an artist. But I always believed that how something looks and feels is one of the functions of any building project or space.’

To an outsider, it could seem as though Heatherwick would rather take a risk on something that might not work, rather than create something forgettable that might work – but he doesn’t see it that way. ‘There can be an incorrect reading of risk,’ he says gently. ‘Let’s take as an example the award-winning UK Pavilion we did at the Shanghai Expo in 2010. The British government gave us half the budget of other western nations, and yet we had to stand out among 200 other pavilions.’

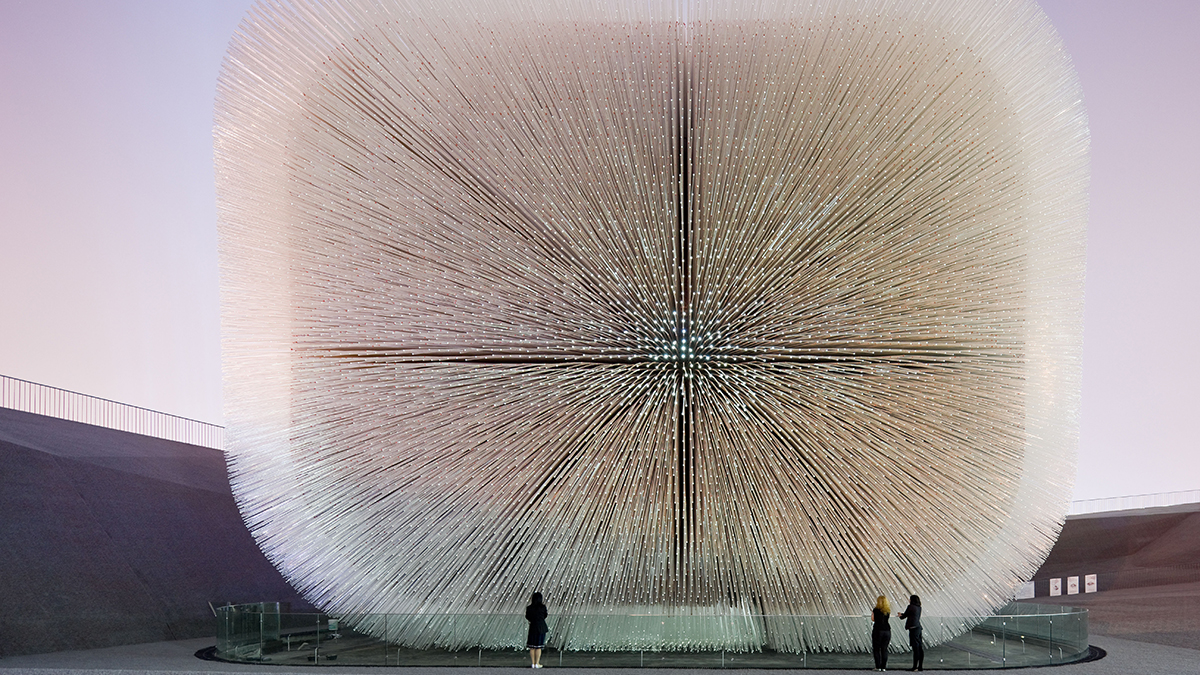

Heatherwick Studio was told their design must be in the top five. So how to dazzle? ‘However good Sherlock Holmes and queens and castles might be, they are attached to an image of Britain that’s been portrayed in China endlessly. What hasn’t been communicated is Britain’s track record of attracting some of the best creatives in the world. Only very simple, powerful things will stand out, so we came up with the Seed Cathedral, a huge box covered in silvery hairs with 250,000 seeds dispersed within their glassy tips.’

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

He laughs; it is a thing of shimmering, delicate beauty, but it looks a great deal better than it sounds. ‘The risk to me was to discuss how much it rains in Britain or to involve tea bags. Doing something extraordinary was therefore the safest thing we could do with British taxpayers’ money.’ He’s right, of course. And it was such a success that he is now working on several large projects in Shanghai, including the Shanghai Bund Finance Centre, a 50/50 collaboration with Foster + Partners.

In the meantime, Heatherwick has become increasingly involved with public space. Although he is juggling dozens of projects at any given time, his current London venture is, of course, the Garden Bridge. Set to sit between the Hayward Gallery and the Oxo Tower on the South Bank, and end adjacent to Somerset House on the Victoria Embankment, the proposed £175m pedestrian bridge has drawn anger from various quarters.

The arguments against include the question of who will fund the project, but surely bringing the rural into the urban is generally a good thing? ‘I think so. Cynicism is in some way part of British creativity. A project in the centre of the city will always encounter some friction; it’d be quite weird if it didn’t. The bridge would start on a disused piece of ground on the south side, in front of London Television Centre, and reach Temple tube station on the north side.

‘The buildings at either end of the bridge appear to have turned their back on the river. LTC has erected a big fence to stop people getting to Graham Norton, and Temple tube, despite being calculated as the true centre of London by the Evening Standard last year, is also the least-used station on the network.’

Heatherwick is no stranger to discord – his 2004 sculpture ‘B of the Bang’ was dismantled in 2009, when one of the spikes fell off – but then few, if any, great creatives sail through their working lives. For Heatherwick, it’s about keeping the faith. And, sometimes, working away from home. ‘London is one of the thought-leading capitals of the world, yet Britain and Europe have a tendency to become slightly smug about their creativity. And, in the former’s case, its eccentricity. In North America, ambition is seen as a form of creativity. It’s not just about the imaginativeness of an idea itself, but also its application.’

And so, Heatherwick is now working on Pier 55 in New York, a park and performance space that takes the form of an oversized pier over the river. He is also, with Danish firm BIG, working to create a new Google headquarters in Mountain View, California. ‘We are trying to get rid of these dead little boxes that are surrounded by car parks and instead make a piece of city that even people who don’t work for Google can walk through.’

Wherever he works, there is always a certain delight in Heatherwick’s designs, as though he wants to entertain as well as serve the public. This makes him laugh again. ‘It surprises me that delight is seen as a separate thing. There’s no reason why the best buildings in the world shouldn’t delight and serve.’

-

The environmental cost of GLP-1s

The environmental cost of GLP-1sThe explainer Producing the drugs is a dirty process

-

Greenland’s capital becomes ground zero for the country’s diplomatic straits

Greenland’s capital becomes ground zero for the country’s diplomatic straitsIN THE SPOTLIGHT A flurry of new consular activity in Nuuk shows how important Greenland has become to Europeans’ anxiety about American imperialism

-

‘This is something that happens all too often’

‘This is something that happens all too often’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day