Does Stagecoach row prove rail privatisation has failed?

After another East Coast franchise runs into trouble, is it time to bring the railways back under state control?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

There are very few people outside the Tory front bench who are willing to defend rail privatisation, despite another headline appearing to strengthen the argument that the networks should be brought back into public ownership.

This morning, Stagecoach reported its East Coast franchise has suffered significant losses that had "punched an £84m hole in its finances", says The Guardian.

Boss Martin Griffiths said the company had overpaid by bidding £412m a year for the eight-year contract in 2015 and that because of Network Rail failing to deliver promised infrastructure upgrades, it would demand a change to the contract terms.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The Department for Transport dismissed the comments, but "the dispute raises the possibility that Stagecoach could end up paying something closer to the £235m" paid previously by the public operator Directly Operated Railways.

This only adds to the disastrous history of the East Coast franchise, which has seen two private companies fail since 2006.

Then there is Southern Rail, which has been rocked by rolling industrial disputes and plummeting service levels. A quirk in the franchising arrangement means that taxpayers are hit, rather than operator Govia Thameslink Railway.

It all sounds like a bit of a mess, doesn't it?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Complex structure

The structure of the privatised railway does look messy, as this diagram from the industry regulator the Office for Rail and Road makes clear.

Most tend to think of the railways in terms of franchised operators, but the reality is much more complicated.

The infrastructure, including the lines themselves, electrical cables, signalling and stations, are owned by Network Rail, which since the failure of Railtrack in the early part of the last decade is a public company.

Then there are the rail operators, which are mostly the companies running the 15 main franchises plus a few smaller firms running "open access" services on some routes. Operators also lease most of the stations along their route from Network Rail.

These firms also lease the rail rolling stock, which is owned and provided mostly by three companies, referred to as rolling stock companies, or "Roscos". For some big infrastructure projects this is bought and provided by the government.

This means that train companies pay for access to track space that is owned by a public company, using trains that are leased from and maintained by other third parties.

The arrangements for these operating companies differ, too. Some run under a full franchising deal that transfers most of the risk to the private sector, like Stagecoach.

Others are franchises like Southern Rail, which because of the upheaval of the Thameslink programme is managed for an annual fee of around £1bn by Govia. Any financial risk is borne by the government.

All of this also means that when you face delays on your rail journey, due to a signalling failure, say, or a train failure, it's probably not the fault of the company from which you bought your ticket.

Need for change

What's clear is that the railways are not working as well as they could be – and some would say this was understating things.

A report from the parliamentary transport select committee shows that passenger satisfaction ratings have been in decline steadily since 2011, while fares have risen by 23.5 per cent since 1995.

At the same time the public subsidy is still substantial. Flat in real terms since 2010, it currently sits at around £4.8bn a year.

As for efficiency, the report states that "UK rail lags considerably behind comparators in continental Europe" with past estimates putting the efficiency gap between the UK and the continent as high as 40 per cent.

This is why unions continually call privatisation a failure and why the Labour party has pledged to return the railways to public ownership if it's returned to power. It's also why, according to YouGov, [4] 60 per cent of the public agree with that policy.

Competition time

The parliamentary transport committee – and Transport Secretary Chris Grayling – both agree with the need for change, but not by taking the railways back into public control again.

The transport committee, chaired at the time of the report by Labour MP Louise Ellman and Grayling, appears to agree that what's needed is more competition.

The problem, says the committee, is that the current model is costly and still results in regional monopolies that have failed to deliver on the promises of privatisation when the process began in 1993.

The committee wants to see more open access arrangements and the reform of franchises as and when they come up for renewal in order to make them smaller and reduce barriers to entry for firms. The idea would be to encourage more companies into the market.

Under the current model, the costs of bidding for big franchises is huge. Companies are required to provide expensive guarantees to cover the risk of them walking away from contracts.

This has meant that despite revenues rising faster than costs in recent years, profit margins for operators have fallen to 2.9 per cent. The number of firms bidding for contracts has similarly declined.

Grayling has also gone public with plans to bring in new operating teams, beginning with the Southeastern franchise when it's renewed in 2018. This will give train companies joint responsibility for tracks and infrastructure along with Network Rail.

For now, the response to the failures of privatisation is more of it, or at least more of the competition it was designed to deliver.

-

What are the best investments for beginners?

What are the best investments for beginners?The Explainer Stocks and ETFs and bonds, oh my

-

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first time

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first timethe explainer Tackle this financial milestone with confidence

-

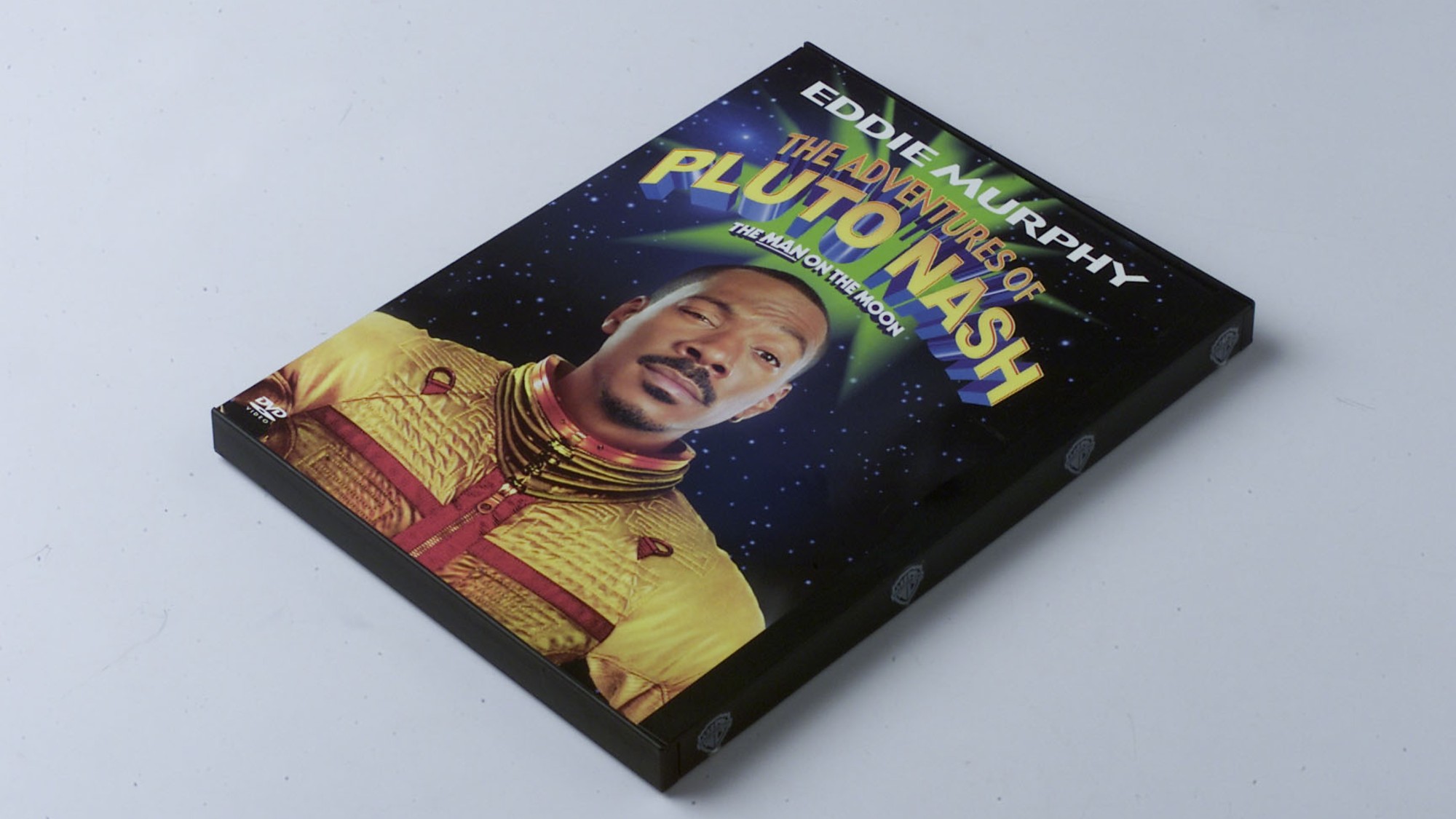

The biggest box office flops of the 21st century

The biggest box office flops of the 21st centuryin depth Unnecessary remakes and turgid, expensive CGI-fests highlight this list of these most notorious box-office losers