Cubitts: an eye for the unique

Founder Tom Broughton on harnessing traditional hand-craftsmanship and modern technologies for a new chapter in London spectacle making

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

I've always had a very emotional relationship with glasses, having worn them all my life. I've therefore been through the experience many times of going to one of those super clinical opticians where there's plastic everywhere, and it's not an enjoyable experience. I thought, frankly, that I could do better.

A big turning point for me was meeting Lawrence Jenkin, one of the last remaining master frame makers, who was a bit of a kindred spirit and basically offered to take me on as an apprentice. Through him I got to understand a bit more about the history behind spectacles. The first-ever pair of glasses was made on Dean Street in Soho in around 1730 by Edward Scarlett, while at the same time John Dollond in Spitalfields was making the first lenses. This essentially created a hugely vibrant industry that thrived for the next 200 years.

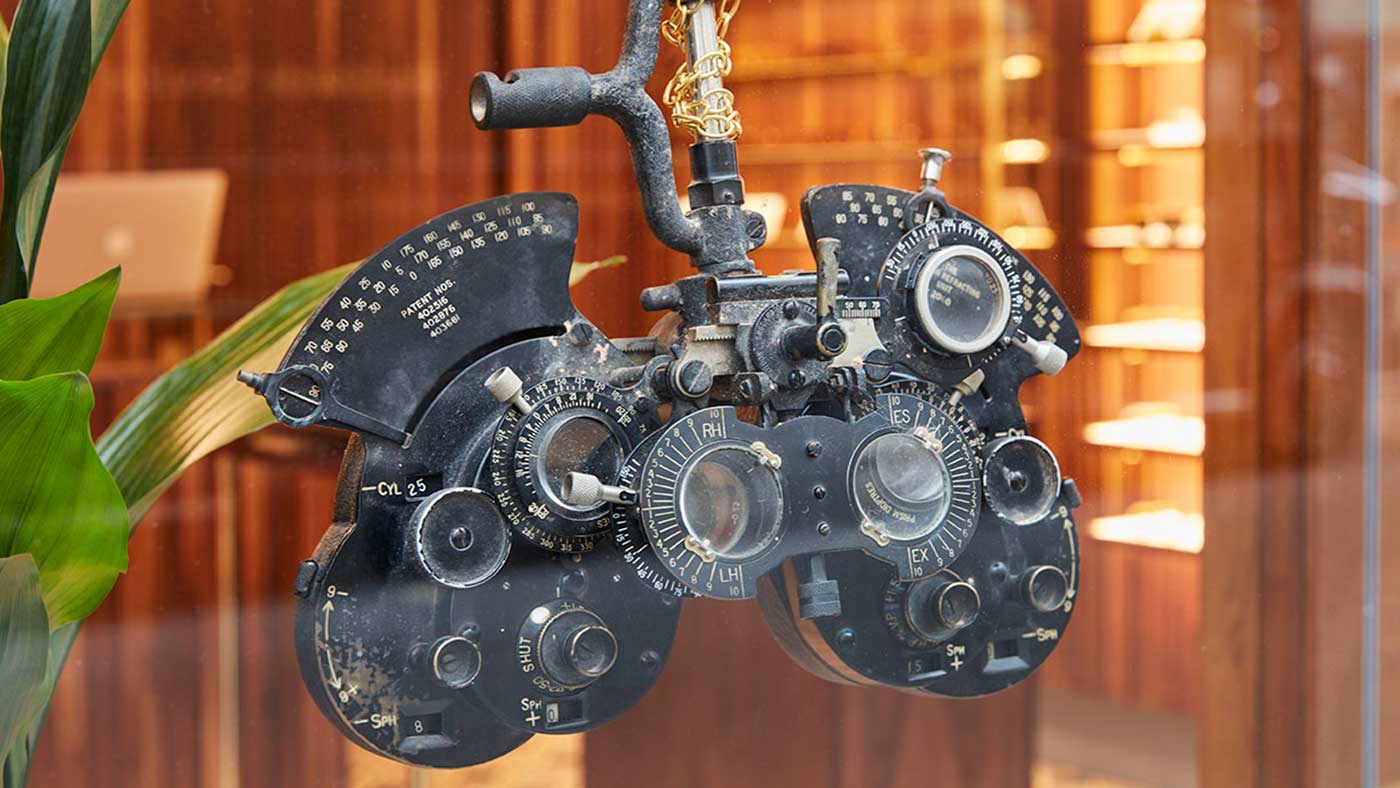

Back then you’d go into a little workshop where someone would test your eyes, and that same person would also design your lenses and frames, and then go out back to make them. Every frame was bespoke and made to order. I wanted to cherry-pick parts of this process and do it in a slightly more up-to-date way. Firstly to be the antithesis of high street opticians, but also to try and use technology and a modern approach to revive some of these more bespoke elements of spectacle making.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

When I first moved to London I ended up living in King's Cross on a road called Cubitt Street. The reason it's called that is because it used to be the building yard of the Cubitt brothers, the three Victorian engineers who moved to the capital from Norfolk and completely revolutionised the way building worked, fuelling the industrial revolution. I thought it was a really interesting principle to apply what they were doing; taking a very old industry and giving it a bit of a shake up, without compromising on the experience and quality of the product.

Our first shop was in the area, and as well as our frames being named after some of the surrounding streets, we've incorporated other references to King's Cross in the products. The butterfly-shaped pins that hold the front to the temples are based on the iron rivets found in the ground around Granary Square, which were laid there by Lewis Cubitt in 1847. King's Cross itself is almost a metaphor for our industry; for a while it wasn't really valued, and now there's a kind of rebirth of people interested in it again.

We've since expanded to a further four stores. What's amazing about London is that it is genuinely steeped with history, and every corner has it's own story to tell, and we always try to take references from the locality and incorporate them into the store. When we opened in Borough Market, we found out the shop had once been a banana wholesaler, which is why we used yellow, and it also used to be the Borough Market Mission Hall, so that's why you see little figures of Jesus around. Our most recent is on Jermyn Street, where we've tried to evoke the feel of a traditional atelier. One of the first residents of the street was Sir Isaac Newton, who wrote a book that led to the production of the first lens. We found out that when he lived there he did a lot of groundbreaking work on geometry, so we incorporated tessellating designs into the tiles.

What I think is really exciting is that we use technology to make relevant traditional skills; we don't want to be too rose-tinted and overly nostalgic about the process. One such project is that we've developed a headscanner using cephalometrics, funded by a government grant we were awarded through Innovate UK. You put your head in the machine and it has two smartphones in it that take images of your face, and then we have a piece of software that meshes them together into a 3D scan. This means the frame can be automatically parametrically fit to someone's face. Then that design can be printed off at the workshop, where someone can start with a saw, a piece of acetate, a scribe and chalk and make it from scratch.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

With our bespoke service we've done all kinds of different commissions. It falls into two categories. Firstly, some people are interested in the aesthetic angle, something bold and unique. We recently created a pair for David Emanuel, who is most famous for designing Princess Diana's wedding dress. He came in and his reference was the Thunderbird character Brains, who has big blue glasses. We made him these huge spectacles that would swamp most people, but they worked amazingly on him. On the other end you have people who have got very practical needs. For example, we made glasses for someone who flies planes at the weekend and couldn't find any that fitted inside his helmet with his voice speaker, or frames for people who have medical conditions that might mean that their face is asymmetrical or similar.

We don't try to be a cutting-edge fashion brand. Our focus is on timeless, carefully considered and enduring shapes and silhouettes with a traditional tinge. The nice thing about eyewear is that most people have two eyes, a nose and two ears, so you don't have to reinvent the wheel every time. At the moment we've got this little baby company, which is four years old, and we're just trying to continue to grow and nurture it without losing our culture or independence.

TOM BROUGHTON is the founder of eyewear brand Cubitts, specialising in spectacles made by hand using traditional techniques; cubitts.co.uk

-

The environmental cost of GLP-1s

The environmental cost of GLP-1sThe explainer Producing the drugs is a dirty process

-

Greenland’s capital becomes ground zero for the country’s diplomatic straits

Greenland’s capital becomes ground zero for the country’s diplomatic straitsIN THE SPOTLIGHT A flurry of new consular activity in Nuuk shows how important Greenland has become to Europeans’ anxiety about American imperialism

-

‘This is something that happens all too often’

‘This is something that happens all too often’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The daughter also rises: remembering the work of May Morris

The daughter also rises: remembering the work of May MorrisIn Depth A new exhibition at the William Morris Gallery focuses on his youngest child, one of the forgotten heroines of the Arts and Crafts movement

-

Petersham Nurseries comes to Covent Garden

Petersham Nurseries comes to Covent GardenIn Depth Managing director Lara Boglione on bringing a taste of the popular Richmond garden shop and cafe to central London

-

Grain & Knot: A cut above

Grain & Knot: A cut aboveIn Depth Founder Sophie Sellu on leaving her office job to start her own business hand-carving wooden utensils

-

The New Craftsmen: Discover beautiful British crafts

The New Craftsmen: Discover beautiful British craftsIn Depth Co-founder Natalie Melton talks about the challenges facing makers today and the joy of handmade homeware

-

London Craft Week: Discover makers, designers and artists

London Craft Week: Discover makers, designers and artistsIn Depth Over 100 of the UK's top talents are opening their studios for tours and masterclasses for a behind-the-scenes glimpse at their work

-

Cheaney & Sons: The changing business of brogues

Cheaney & Sons: The changing business of broguesIn Depth William Church of the Northampton-based shoemakers talks about the future of British-made brogues

-

School of rock: Create objets d'art with a master craftsman

School of rock: Create objets d'art with a master craftsmanIn Depth Want to fashion your very own masterpiece? Ditch night school and enrol with an established atelier

-

Artist Peter Layton on the sheer joy of glass

Artist Peter Layton on the sheer joy of glassIn Depth The renowned founder of London Glassblowing makes a clear case for an underappreciated art form