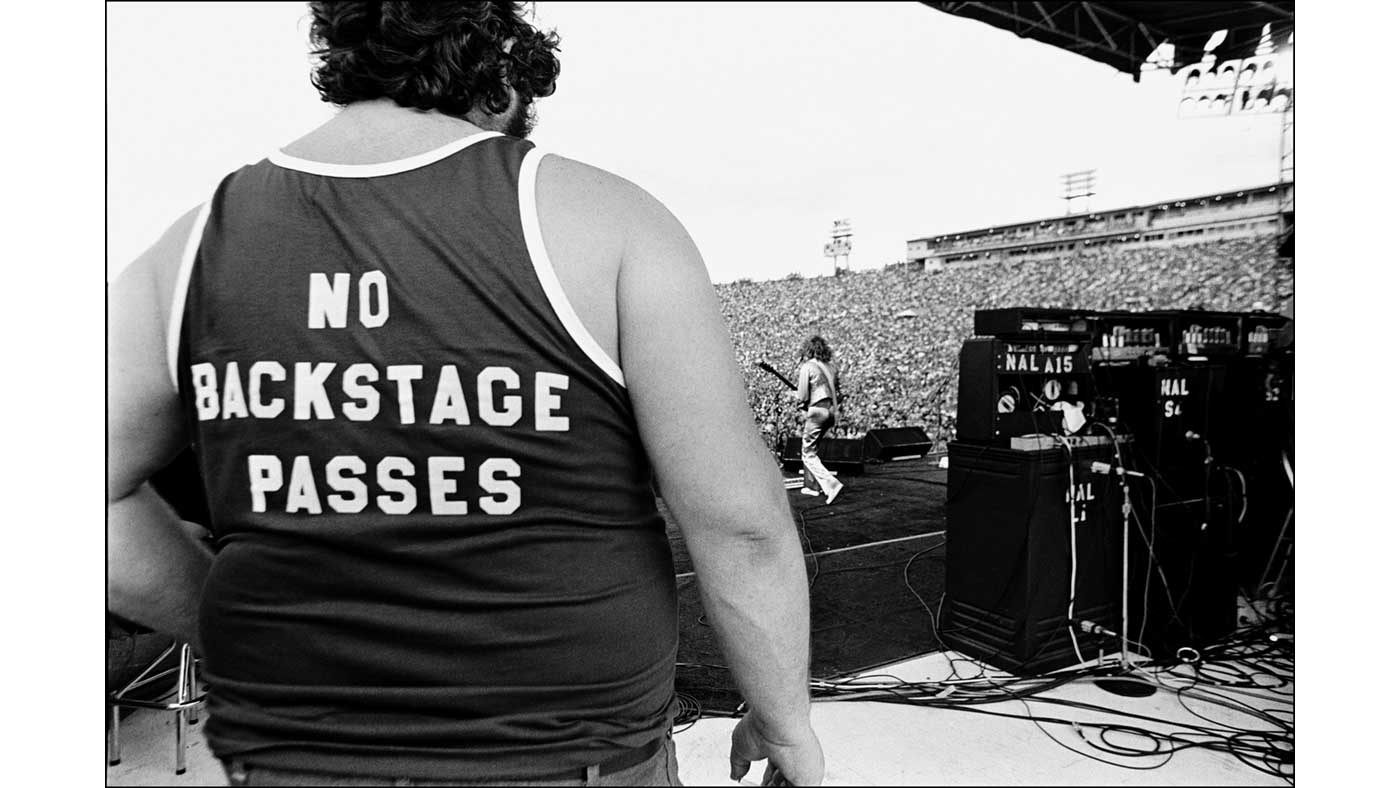

Neal Preston: exhilarated and exhausted

The prolific music photographer reveals how it all began, as he releases a memoir spanning 47 years on the road with rock 'n' roll royalty

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

I didn’t make a decision to become a photographer; it had already been made for me. It sounds supernatural but I absolutely believe that to be true. I believe photography and rock music have always been embedded in my DNA – I just didn’t know it until 1964.

Sometime between my 11th and 12th birthdays, my brother-in-law gave me my first “real” camera – an Ansco Speedex 4.5. It had a button on top that you’d press and a bellows with a lens would pop out. To me, it looked like a big-time piece of professional photo equipment but I wasn’t intimidated by it, just fascinated.

I noticed the lens had two rings that you could move, each with little numbers on them. So, like any kid, I fiddled around, having no idea what any of the numbers meant. I pressed what was obviously the shutter release button, but nothing happened. Zero. I have no idea why I didn’t pull it apart, since I was the kind of kid who would take things apart to find out how they worked and then get bored and never put them back together. This camera was different, though.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

I figured out that if you moved a small silver tab over to the left there was a spring that would click and lock the tab in place, and then if you pressed the shutter release the camera would fire. It was very simple: cock the shutter and press the button. That was it, I was hooked. It was love at first sight.

To me, that Ansco was more than a camera; it was a magical box that made everything feel like home. I instinctively understood how cameras worked – the relationship between the lens and the shutter, the difference between fast film and slow film… everything about photography made sense to me.

I’ve always considered myself a photojournalist at heart. As a kid I spent every penny I had on magazines relating to whatever hobby I was pursuing at the time. Eventually it became all about the pictures. As my interest in photography grew, it was inevitable that I would discover the most important magazine in the country, if not the world: Life magazine. The first time I saw it I was smitten.

Life always had the best pictures and the splashiest layouts, and to me it was the biggest, baddest and most influential magazine in the world. I was especially drawn to any photo that had a “behind the scenes” feel to it. Photos shot on movie sets – where you could see the lights and the crew in the frame, in make-up rooms or an actor’s trailer – would intrigue me and not because of who the subject was, it was something far more seductive than that. The Life staffers were the biggest studs in the photo business. They could shoot anything, in any style, at a moment’s notice. And even more incredible was the fact that they’d deliver the goods week after week.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Clearly there was a lot more that went into getting those pictures than just showing up somewhere and pressing a button. I wanted to know how they ended up at Life, how they got their assignments, and what they had to go through during each photo session. How did all of this work? How does anyone get there? In my mind, those guys hadn’t just been chosen by the editors at Life – they’d been anointed. I’d stumbled upon a sort of secret society that spoke to me, and I wanted in.

Then, on the night of 9 February 1964, my entire universe changed in one hour, when I saw the Beatles make their American TV debut on The Ed Sullivan Show. It was as if I’d picked up a ringing phone and the voice on the other end said: “Neal – turn on the TV and you’ll see the rest of your life. Have a great time.” I simply cannot stress the magnitude of what took place in that one hour. A nuclear bomb exploded in my brain, delivered straight to my cortex by John Lennon.

I was almost 12 years old at the time – that’s about as impressionable an age a boy can be. I’m pretty certain I hit puberty that night, and it wasn’t a long-drawn-out affair, it was a massive hormonal blast. Overnight, I fell in love with rock music (and women), in addition to my new fascination with cameras and photography. All the emotional switches in my brain had been flipped on.

Shooting live music performances is something few photographers do really well. I just happened to discover one day that I was pretty good at it. You can’t teach it, you can’t learn it, you just do it: one part love of photography, one part love of music, one part love of theatre and theatrical lighting, one part hero worship, one part timing and 95 parts instinct.

I grew up around showbiz – my father worked as a production stage manager for the biggest Broadway musicals of the 20th century. Going to visit him backstage at work was my greatest joy as a kid, so it’s no wonder I developed a Pavlovian reaction to walking through stage doors. To this day it doesn’t matter what venue I’m at, when I go backstage I’m still that little boy in the wings watching my dad calling the lighting cues for My Fair Lady and Fiddler on the Roof.

And then one afternoon it all magically came together, on a fluke. Bringing a camera to whatever rock shows I could afford to see was a no-brainer and part of my natural evolution as a photographer. I don’t remember what the first concert I photographed was, but I do remember the first on-stage photo I shot. I brought a camera to the theatre and snuck a photo of the lead understudy during a Saturday matinee of Fiddler on the Roof. I only shot one frame. I’d seen the show so many times I knew exactly when the audience would laugh and that’s when I stole my shot, knowing the laughter would cover up the sound of my shutter firing.

The shot looked pretty nice so I gave my dad a print of it. He showed it to the actor, a nice fellow by the name of Harry Goz, who liked it so much he gave me a huge set of books about photography. I devoured them, cover to cover, on a weekend reading binge. That’s how it started. I was off to the races.

Neal Preston is a rock photographer best known for his images of music’s biggest stars including Led Zeppelin, Queen, Bruce Springsteen, The Who, The Rolling Stones, Fleetwood Mac, Michael Jackson and many more. The book, Neal Preston: Exhilarated and Exhausted, featuring the above introduction, is a complete retrospective of his 40-plus-year career, containing more than 300 photographs from his extensive archive, alongside stories about life on the road. £45, Reel Art Press; reelartpress.com

-

Kia EV4: a ‘terrifically comfy’ electric car

Kia EV4: a ‘terrifically comfy’ electric carThe Week Recommends The family-friendly vehicle has ‘plush seats’ and generous space

-

Bonfire of the Murdochs: an ‘utterly gripping’ book

Bonfire of the Murdochs: an ‘utterly gripping’ bookThe Week Recommends Gabriel Sherman examines Rupert Murdoch’s ‘war of succession’ over his media empire

-

Gwen John: Strange Beauties – a ‘superb’ retrospective

Gwen John: Strange Beauties – a ‘superb’ retrospectiveThe Week Recommends ‘Daunting’ show at the National Museum Cardiff plunges viewers into the Welsh artist’s ‘spiritual, austere existence’

-

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency – an ‘engrossing’ exhibition

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency – an ‘engrossing’ exhibitionThe Week Recommends All 126 images from the American photographer’s ‘influential’ photobook have come to the UK for the first time

-

Why photo booths are enjoying a revival

Why photo booths are enjoying a revivalIn The Spotlight It’s 100 years since it first appeared, but the photo booth is far from an analogue relic

-

Lee Miller at the Tate: a ‘sexy yet devastating’ show

Lee Miller at the Tate: a ‘sexy yet devastating’ showThe Week Recommends The ‘revelatory’ exhibition tells the photographer’s story ‘through her own impeccable eye’

-

Resistance: 'compelling' show captures a century of protest

Resistance: 'compelling' show captures a century of protestThe Week Recommends Turner prizewinner Steve McQueen curates 'fascinating' photography exhibition in Margate

-

Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: experimental portrait photography

Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: experimental portrait photographythe week recommends Their careers are separated by time but joined by their shared interest in spectral, dream-like atmospheres

-

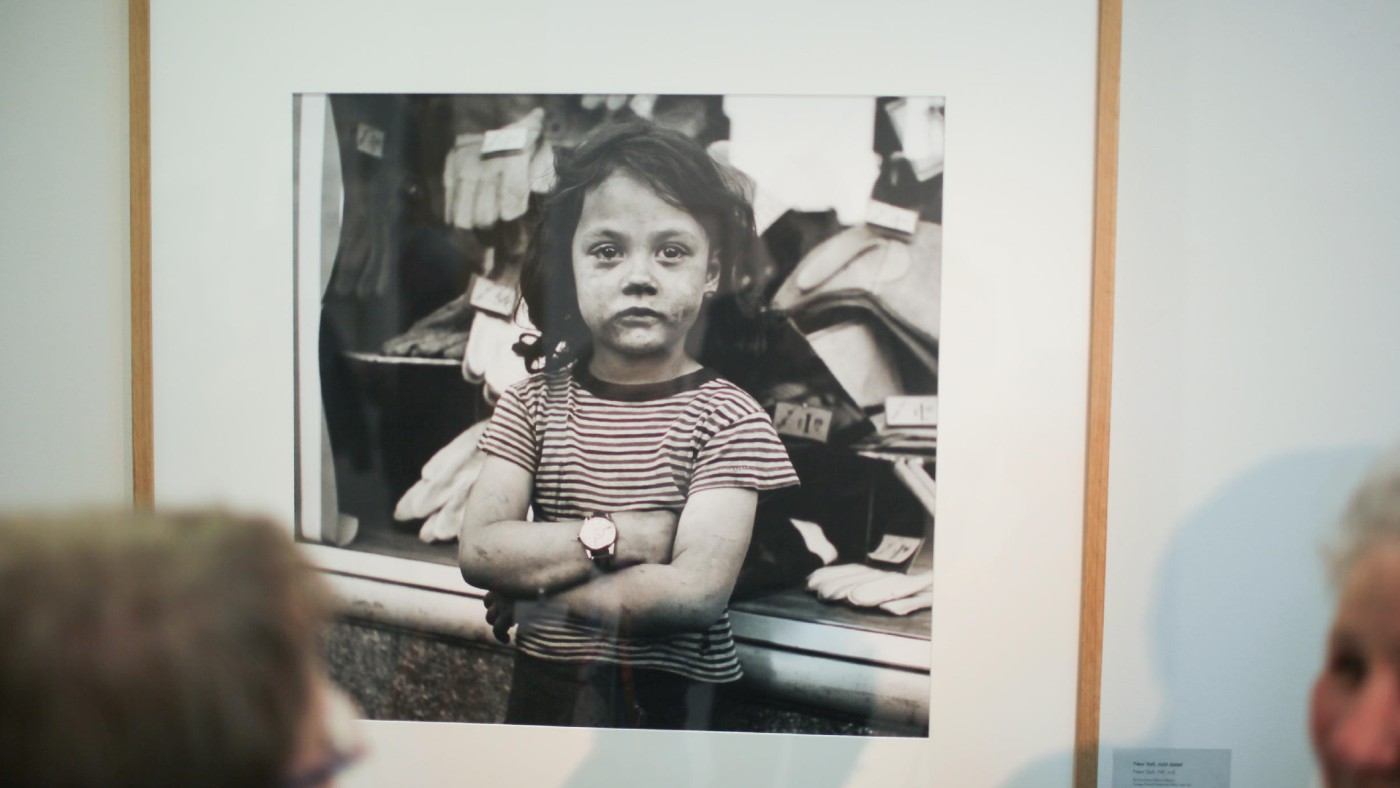

Chris Killip: Retrospective at The Photographers’ Gallery review

Chris Killip: Retrospective at The Photographers’ Gallery reviewThe Week Recommends Superb and timely exhibition features ‘beautiful and painfully moving’ images

-

Vivian Maier: Anthology – this MK Gallery show is ‘pure pleasure’

Vivian Maier: Anthology – this MK Gallery show is ‘pure pleasure’The Week Recommends Exhibition marks first time that Maier’s photography has been shown in the UK

-

Magnum Photos: Where Ideas Are Born – 20th century art icons in their studios

Magnum Photos: Where Ideas Are Born – 20th century art icons in their studiosUnder the Radar An intimate look at modern and contemporary masters shot by legendary Magnum photographers