What is HPV and who is eligible for the vaccine?

Major study shows vaccinated women in their 20s are 87% less likely to have cervical cancer

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Hundreds of women have avoided cervical cancer thanks to the human papillomavirus (HPV) jab, according to the first direct global evidence of the vaccination programme.

Schoolgirls aged 12 and 13 have been offered the HPV vaccine in the UK since 2008. A study, by Kings College London and published in The Lancet, found that rates of cervical cancer in vaccinated women now in their 20s were 87% lower than those who were unvaccinated.

This meant that by June 2019, there were an estimated 450 fewer cases of cervical cancer and 17,200 fewer cases of cervical carcinomas (pre-cancers).

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Michelle Mitchell, chief executive of Cancer Research UK, which funded the study, said the results “show the power of science”.

“It’s a historic moment to see the first study showing that the HPV vaccine will continue to protect thousands of women from developing cervical cancer,” she added.

What is HPV?

According to the NHS website, HPV is the name for a group of viruses that affect your skin and the moist membranes lining your body.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Such membranes include the cervix, mouth, throat and anus.

There are more than 100 types of HPV. Around 30 of them can affect the genital area, and can be passed from person to person through sex.

Some HPV types have been linked to the development of certain cancers, including cervical cancer. The NHS says that 99.7% of all cervical cancers are caused by an infection with a high-risk type of HPV.

Experts stress that the majority of HPV infections do not cause any problems and that our immune systems can get rid of them.

Can HPV be treated?

There is no treatment for the virus itself. However, there are treatments for the health problems that HPV can cause, including genital warts and certain cancers.

If you have HPV and the virus has caused abnormal cells, you may require treatment. For women, going for smear tests is the best protection against cervical cancer, since the tests can identify abnormal cells before they have a chance to develop into cancer.

What vaccine is used?

The Lancet study published yesterday looked at data from a vaccine called Cervarix, initially offered to girls when the vaccination programme rolled out in the UK 13 years ago. It protected against two types of HPV: 16 and 18, which are the cause of most cervical cancers in the UK.

In 2012, it was replaced by Gardasil, which also protects against types 6 and 11, which cause 90% of genital warts.

During this academic year, the vaccine will be replaced again by Gardasil 9, which covers a further five types of HPV (31, 33, 45, 52 and 58), which can also cause cervical cancers, as well as anal cancers and some genital, head and neck cancers.

Who is eligible for the vaccination?

Since 2008, girls have been offered their first injection at the age of 12 or 13 at school, with a second dose between six and 12 months later. The jabs are free on the NHS up until the age of 18.

From September 2019, boys aged 12 to 13 also started receiving the jab free of charge at schools around the UK.

“The HPV vaccine works best if boys and girls get it before they become sexually active,” explained the BBC.

Gay men can also have a free HPV vaccine from their doctor up to the age of 45, as they do not benefit from the indirect protections offered by the widespread vaccination of girls.

The injection is available from private pharmacies, but can cost around £470 for the course and each company has different eligibility criteria.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The truth about vitamin supplements

The truth about vitamin supplementsThe Explainer UK industry worth £559 million but scientific evidence of health benefits is ‘complicated’

-

Covid-19 mRNA vaccines could help fight cancer

Covid-19 mRNA vaccines could help fight cancerUnder the radar They boost the immune system

-

Deadly fungus tied to a pharaoh's tomb may help fight cancer

Deadly fungus tied to a pharaoh's tomb may help fight cancerUnder the radar A once fearsome curse could be a blessing

-

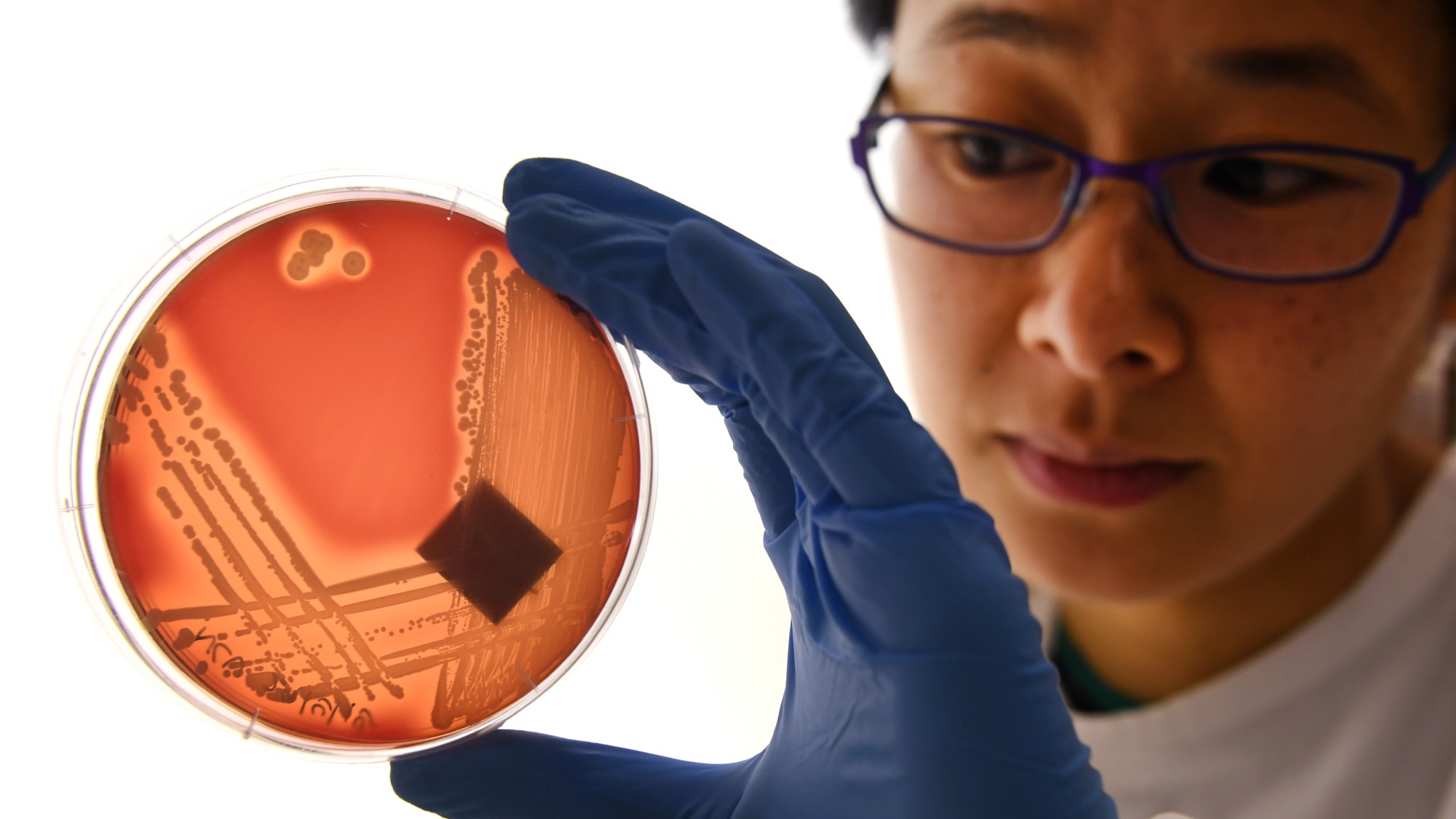

'Poo pills' and the war on superbugs

'Poo pills' and the war on superbugsThe Explainer Antimicrobial resistance is causing millions of deaths. Could a faeces-filled pill change all that?

-

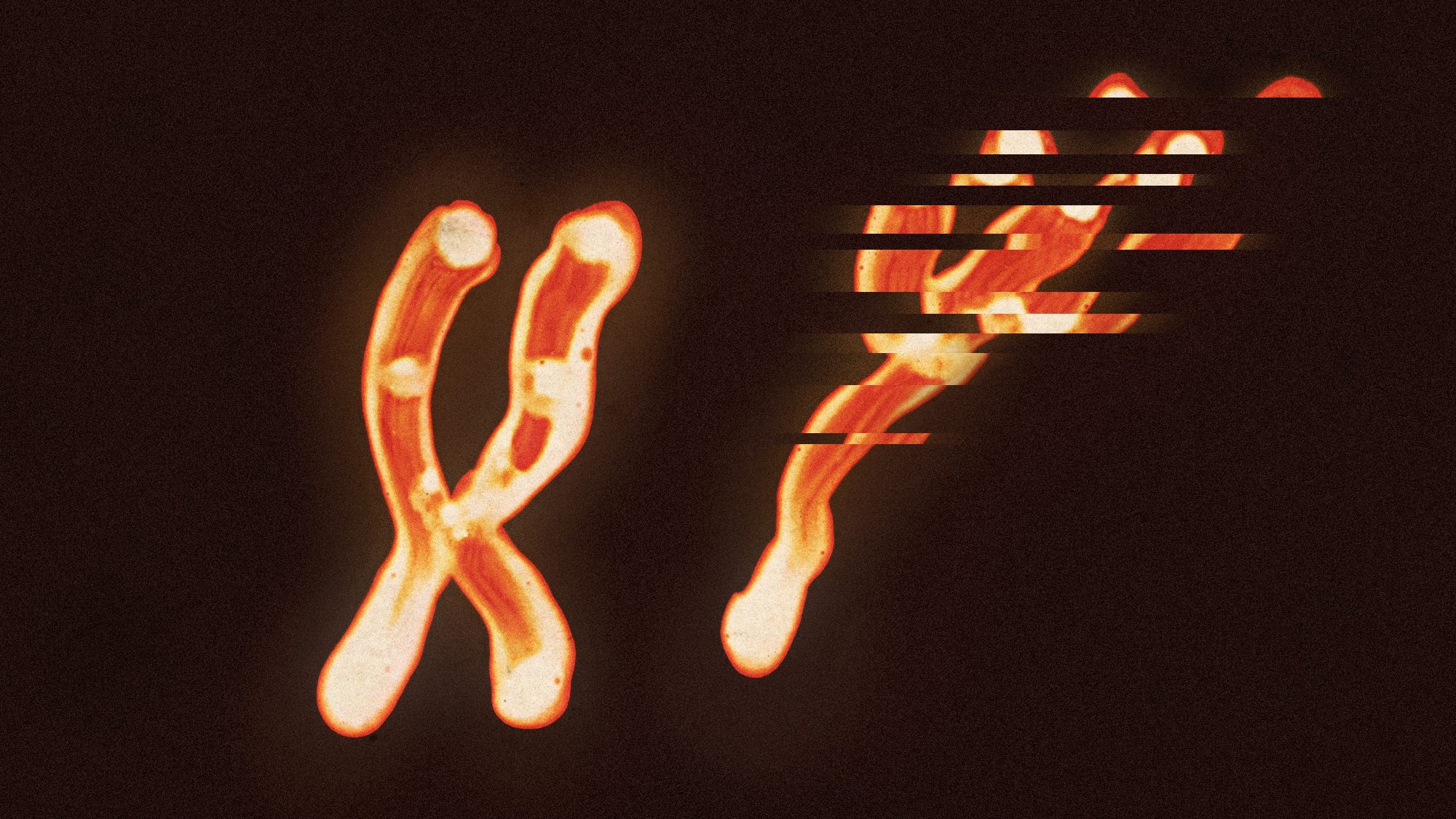

The Y chromosome degrades over time. And men's health is paying for it

The Y chromosome degrades over time. And men's health is paying for itUnder the radar The chromosome loss is linked to cancer and Alzheimer's

-

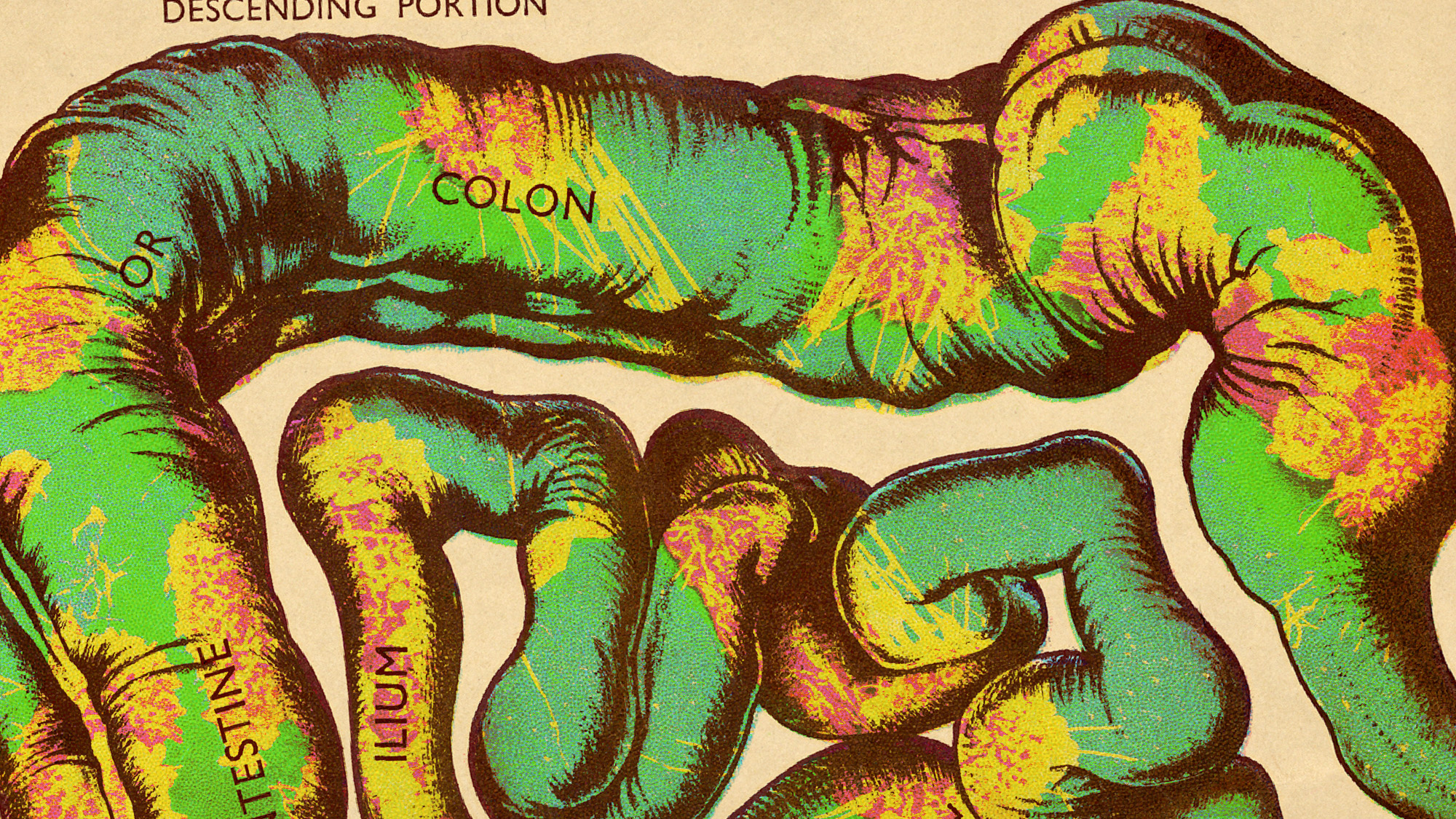

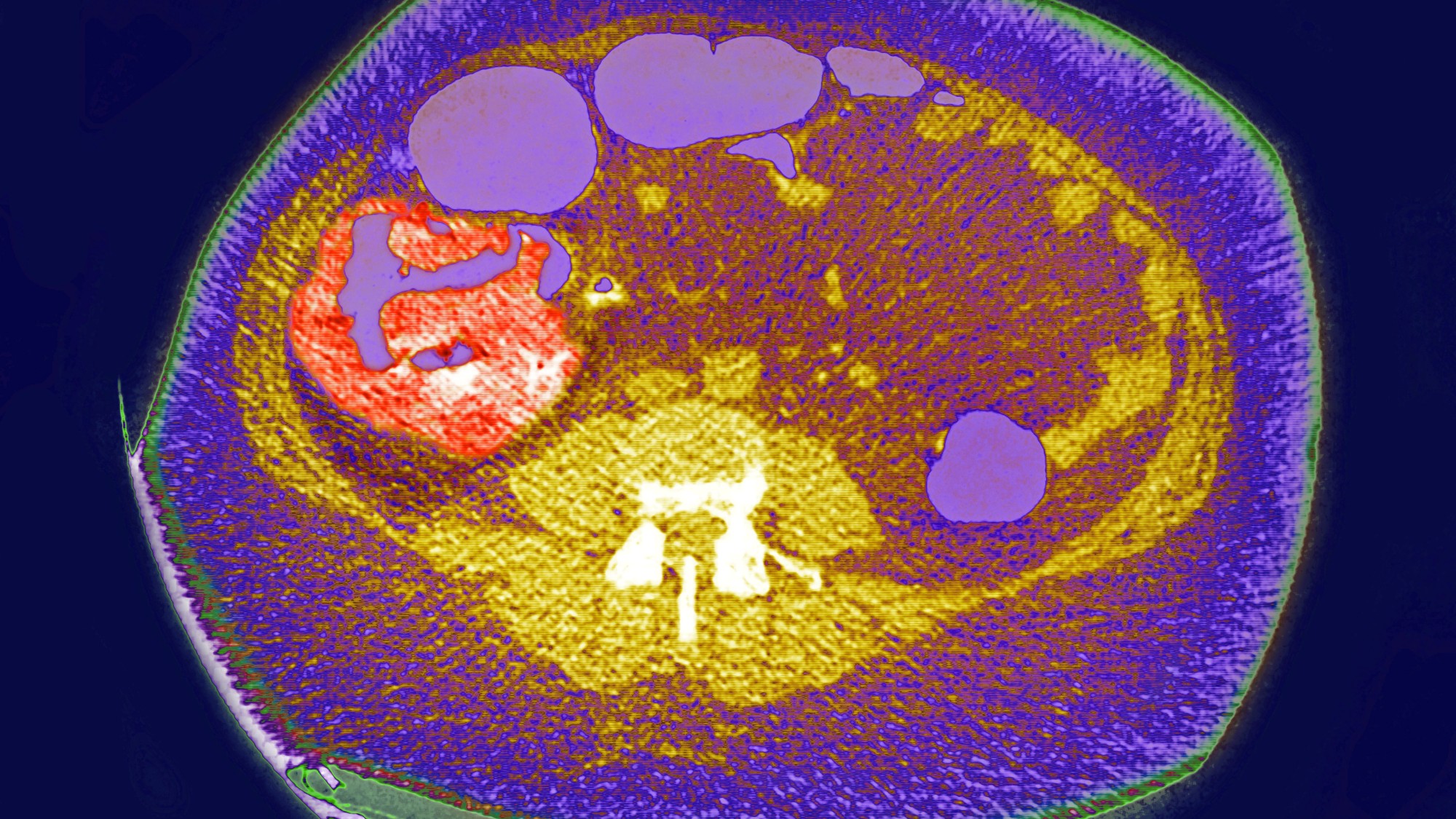

A bacterial toxin could be contributing to the colorectal cancer rise in young people

A bacterial toxin could be contributing to the colorectal cancer rise in young peopleUnder the radar Most exposure occurs in childhood

-

Why are more young people getting bowel cancer?

Why are more young people getting bowel cancer?The Explainer Alarming rise in bowel-cancer diagnoses in under-50s is puzzling scientists

-

Five medical breakthroughs of 2024

Five medical breakthroughs of 2024The Explainer The year's new discoveries for health conditions that affect millions