The fashion for flowers: Constance Spry

An exhibition at London’s Garden Museum celebrates Spry’s taste for modernity

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In November 1928, a Mayfair floral display created a furore. Two years prior, the heritage perfumer Atkinsons London had commissioned architect Vincent Harris to erect its flagship, a towering edifice in the Gothic revival style, located where Old Bond Street crosses with Burlington Gardens. To furnish the ground floor boutique, Atkinsons had called upon Norman Wilkinson, the artist and theatre designer. In turn, Wilkinson asked his friend Constance Spry to conceive the arrangements to bloom in the shop windows. And so it was that flowers drew crowds of such numbers that the police had to be drafted in, for Spry had an idiosyncratic take on her métier.

For this commission, she mixed bright green cymbidium orchids with red-brown foliage, foraged hedgerow flowers, weeds, clematis seed heads and brambles, blackberries ripening. Defying tradition, Spry found beauty in the often overlooked, and mixed freely, a practice that was to become her signature. Dotted with rare hothouse blooms, grasses, berries, hops, wild clematis, kale and pussy willows have all featured in Spry arrangements.

Her inspirations came from Old Master paintings finished between the 16th and 18th century in the Dutch tradition – the still lifes of Georgius Jacobus Johannes van Os, say, or works by Ambrosius Bosschaert – and, closer to home, the patches of green she nurtured. “Spry was very keen to use things from gardens,” says floral designer Shane Connolly. “Vegetables, branches, weeds, brambles. She used a whole gamut of things.”

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Recently, Connolly delved into Spry’s archives and the holdings of the RHS Lindley Library to prepare Constance Spry and the Fashion for Flowers, an exhibition at London’s Garden Museum which he co-curated. In situ until September this year, Connolly unearthed 100 never-before-seen assets for the show, including photographs and personal ephemera. “She did not follow fashions of her time,” he says of Spry, whose biography makes for fascinating reading. Born in Derby and raised in Ireland, Spry previously worked as a lecturer and secretary of the Dublin Red Cross. In 1921, she arrived at Homerton and South Hackney Day Continuation School to teach classes in cookery and flower arranging, having accepted the post of headmistress and left behind her first marriage.

When Wilkinson first brought up Atkinsons’ boutique displays, Spry had recently opened her debut venture. Her Flower Decoration shop on Belgrave Road also opened in 1928; a success, in 1934 Spry moved to larger premises on South Audley Street. Here, she added education to her offering – in the shape of the Constance Spry Flower School – and soon employed a team of 70 people.

“Everyone who worked there said it was the most elegant thing,” says Connolly of Spry’s shop, which was painted white (a neutral backdrop to vibrant flowers and plants) and overseen by staff dressed in grey pinafore dresses designed by South African-born British couturier Victor Stiebel, whose creations, finished on nearby Bruton Street, were more readily found in the wardrobes of Katharine Hepburn or Princess Margaret.

Like Stiebel, Spry too soon commandeered a list of high society clients. This included once-in-a-lifetime events: chronicled at the Garden Museum are the headline-making weddings Spry accented with her bouquets and arrangements.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Following a winter day’s theme, it was white artificial flowers matched with frosted palm leaves and hazel branches sprayed white for the January 1933 ceremony of Nancy Beaton and Sir Hugh Smiley (two pure white doves in a white cage also featured); three years later, Liza Maugham found Spry’s bouquet of mixed white flowers to be the perfect match to the white lame Schiaparelli gown she donned for her wedding to Vincent Paravincini, then said to be the catch of the season. For Maugham, Spry also dreamt up a floral headpiece.

A 1937 wedding introduced her to audiences across the Atlantic, as the Duke and Duchess of Windsor tied the knot with Spry’s arrangements within view. Soon, she embarked on lecture tours – a pitstop included the Brooklyn Botanic Gardens – and in November 1939, Spry launched her business stateside, opening a Manhattan boutique on East 54th Street. “One of the things she said, and which I love, was ‘first and foremost, I am a gardener’,” says Connolly. “I think that was the thread, that she liked comfort, she liked nature, she always had flowers in rooms. That was just her way; plants, flowers.”

As on display at the Garden Museum, Spry’s 30-year career in floristry is striking for its many avenues. Prolific in her output – she authored 13 books, among them Come into the Garden, Cook (1942) and the 1952 success How to do the Flowers, and partnered with makers such as Royal Brierley, with whom she created a line of crystal glass vases that are tactile in finish – Spry also promoted the work of her collaborators, many of whom were women. This includes Florence Standfast, a long-term friend who, when faced with financial difficulties, was offered employment by Spry to create artificial flowers. Soon, Standfast magicked up fantastical hand-painted blooms from paper dipped in hot wax.

Standfast also drafted the Datura Vase, one of several vessels Spry produced in partnership with the Fulham Pottery. “My grandmother always had Fulham vases in New Zealand, she used them mostly for floral art, competitive flower arranging, at agricultural and pastoral shows,” says Charlie McCormick. The gardener has since been adding to the ancestral collection. “Although I collect the vases, they are used every day. Some I have even dropped, or they have been knocked and broken – then mended,” he enthuses. “Everything [Spry] stood for I’m interested in – but I would say her influence is to do with a spirit of life more than anything else. Her passion for gardening.”

In addition to her Datura, Standfast dreamt up other Fulham Pottery designs, too; meanwhile, artist and stage designer Oliver Messel joined forces with Spry to perfect vases for the coronation of Edward VIII, which ended up being used for the coronation of George VI. Spry followed the May 1937 event with another royal occasion, when in June 1953 she installed flowers at Westminster Abbey for the coronation of Elizabeth II. There were floral arrangements along the processional route from Buckingham Palace to Westminster Abbey too, and so it came that Spry stopped traffic once again.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

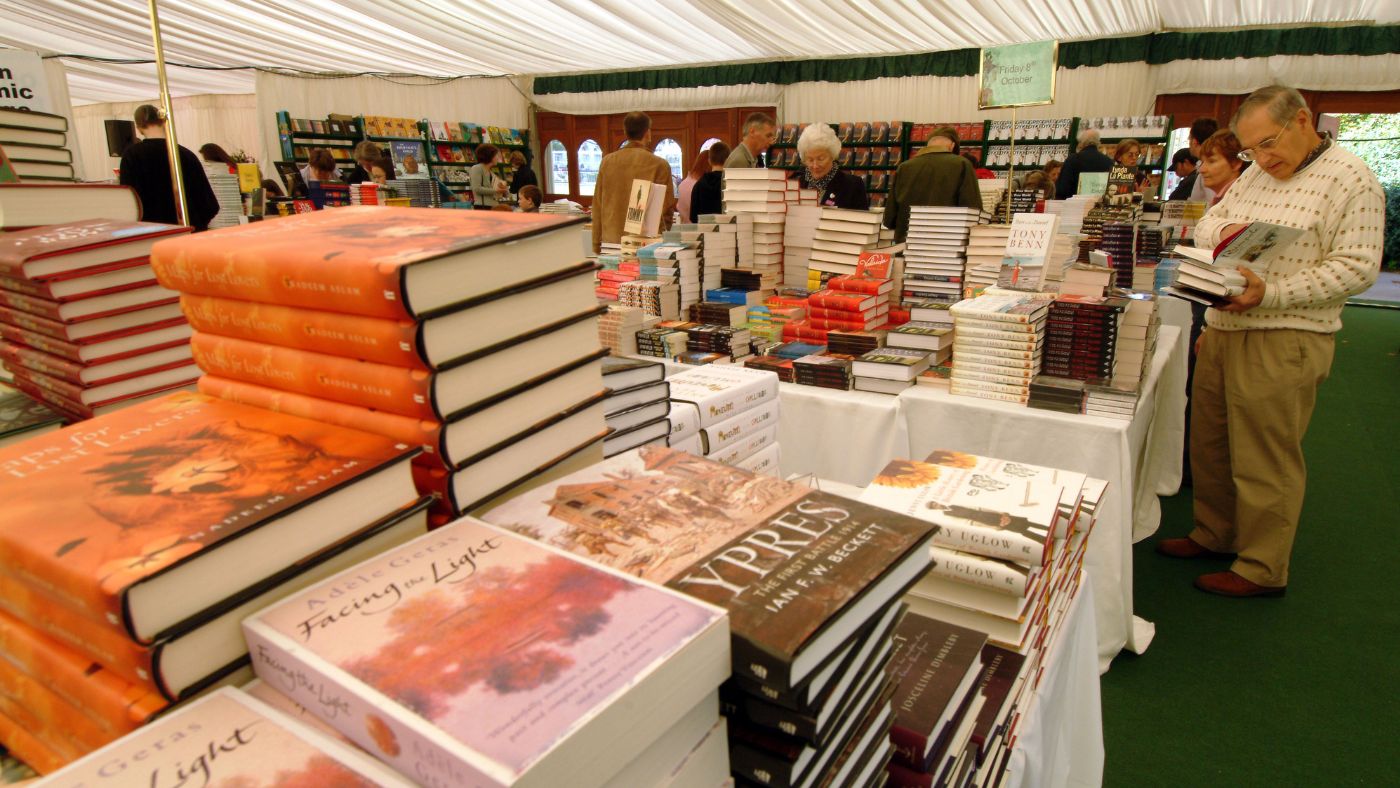

Best UK literary festivals and book fairs in 2023

Best UK literary festivals and book fairs in 2023feature A look at some the biggest events for book lovers in Britain in 2023

-

Fabulous foodie adventures in Peru, Japan and Australia

Fabulous foodie adventures in Peru, Japan and Australiafeature Featuring a Peruvian pilgrimage and foraging in the Volcanic Lakes and Plains

-

Top 10 best debut novels of all time

Top 10 best debut novels of all timefeature Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone took top spot in a poll of British literary lovers

-

Watership Down: disturbing children’s film finally loses its U rating

Watership Down: disturbing children’s film finally loses its U ratingfeature The 1978 adaptation of Richard Adams’s novel no longer feels ‘suitable for all’

-

How to pack efficiently and save on airfares

How to pack efficiently and save on airfaresfeature Travel tips and hacks for making the most of a bargain flight

-

Edge of Ember: affordable fine jewellery for classicists

Edge of Ember: affordable fine jewellery for classicistsfeature London-based brand has gone from strength to strength with its youthful and elegant designs

-

‘Pinnacle of gastronomy’: how Central became the world’s best restaurant in 2023

‘Pinnacle of gastronomy’: how Central became the world’s best restaurant in 2023feature Flagship Lima restaurant of chefs Virgilio Martínez and Pía León is an ‘ode to Peru’

-

Wandering star: Audemars Piguet’s new Code 11.59 Starwheel watch

Wandering star: Audemars Piguet’s new Code 11.59 Starwheel watchfeature Engmatic and alluring, this timepiece has a suitably spiritual backstory