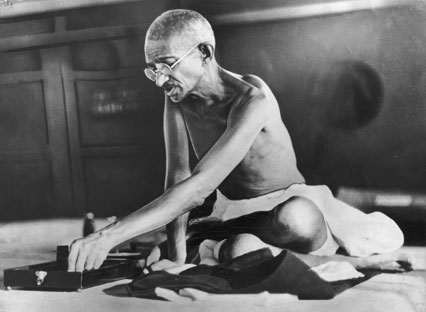

Was Gandhi racist?

Famed Indian independence leader’s views on black Africans are still the subject of intense debate

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The decision to remove a statue of Mahatma Gandhi from the University of Ghana campus in Accra has reignited the debate over the political icon’s stance on race.

The monument was taken down on Wednesday morning, just two years after it was first unveiled, following a campaign by students and faculty members, reports Ghanaian newspaper the Daily Graphic.

Most of the controversy over the Indian independence leader’s racial views arises from comments he made during his time in South Africa, where he lived between 1893 and 1914.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Gandhi’s previously dormant political consciousness were awakened by the intense racial prejudice he experienced in South Africa after going there to practice law, sparking his interest in the Indian nationalist movement.

However, at the time he appeared to have little sympathy for the black victims of South Africa’s white supremacist racial hierarchy, whom he frequently referred to by the disparaging slur “kaffir”.

In fact, his protests over the treatment of Indians by white authorities frequently expressed indignation that they were being put on a par with black Africans.

In a speech in Bombay (now Mumbai) in 1896, he accused Europeans of trying to “degrade” Indians to the level of “the raw kaffir whose occupation is hunting, and whose sole ambition is to collect a certain number of cattle to buy a wife with and, then, pass his life in indolence and nakedness”.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In a letter written in 1905, he complained that “of all places in Johannesburg, the Indian location should be chosen for dumping down all kaffirs of the town”, describing the presence of black natives in the Indian district as “very unfair to the Indian population”.

And following a court case over restrictions that permitted only white settlers to own firearms, he complained that “the Asiatic has been most improperly bracketed with the native”.

“Gandhi believed in the Aryan brotherhood. This involved whites and Indians higher up than Africans on the civilised scale. To that extent he was a racist,” Ashwin Desai, author of The South African Gandhi: Stretcher-Bearer of Empire, told the BBC’s India correspondent Soutik Biswas.

In the book, Desai and co-author Goolam Vahed argue that Gandhi’s advocacy for Indians in South Africa envisioned them as a “junior partner” in white minority rule over the native Africans.

"Thank God he did not succeed in this as we would have been culpable in the horrors of apartheid,” Desai said.

However, The New Yorker expresses the more charitable view that “the young and callow Gandhi failed to recognise the necessity of a broader struggle against racial-ethnic supremacism”, developing a more mature understanding after returning to India in 1915.

The Boer War seems to have been the catalyst for an evolution in Gandhi’s views. He served as a battlefield stretcher-bearer alongside black Africans, and by the Zulu war of 1906 he was defying orders by attending to wounded Zulus as well as British soldiers.

Speaking at the Johannesburg YMCA in 1908, Gandhi paid tribute to the black labour without which colonial South Africa would have been a “howling wilderness”, according to Ramachandra Guha’s biography Gandhi Before India.

On his return to India, Gandhi not only became the most recognisable leader of the movement for Indian independence, but also a vocal opponent of India’s caste system and a staunch defender of the rights of the lowest caste, the so-called “untouchables”.

Gandhi’s defenders argue that his opposition to caste segregation and his success in uniting Indians against European colonialism have acted as an inspiration for black freedom fighters, outweighing or at least counterbalancing his earlier prejudice.

Indeed, Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela both cited Gandhi’s non-violent civil disobedience as an inspiration for their own activism.

Gandhi was an individual with faults and flaws, but his life “shows how an ordinary human being who has many weaknesses can rise to great heights by shedding his early prejudices and by adhering to love and non-violence”, concludes Delhi-based news site The Wire.

-

The environmental cost of GLP-1s

The environmental cost of GLP-1sThe explainer Producing the drugs is a dirty process

-

Greenland’s capital becomes ground zero for the country’s diplomatic straits

Greenland’s capital becomes ground zero for the country’s diplomatic straitsIN THE SPOTLIGHT A flurry of new consular activity in Nuuk shows how important Greenland has become to Europeans’ anxiety about American imperialism

-

‘This is something that happens all too often’

‘This is something that happens all too often’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day