The Taliban: America's once and future allies?

What the fall of Saigon really reveals about America and Afghanistan

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In April of 1975, the North Vietnamese Army in cooperation with the Viet Cong captured the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon and forced the last Americans in the country into a hasty evacuation. It was a humiliating end to the Vietnam War — then America's longest conflict.

It took 20 years and the end of the Cold War for President Bill Clinton to normalize relations with America's former enemies. Twenty years after that, President Barack Obama hosted the leader of the Vietnamese Communist Party at the White House as part of an effort to turn our former adversary into an ally against a rising China. By 2019, Vietnam had become one of the most rapidly-growing tourist destinations for Americans, and Americans were the largest non-Asian source of tourists to Vietnam.

The rapid collapse of the Afghan government and military over the past week, revealing in brutal clarity how little was achieved with 20 years of effort, has already prompted many comparisons to the fall of Saigon. So how long will it take for us to follow the rest of the Vietnam script, and ally ourselves with our Taliban enemies?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

I won't be shocked if it takes much less than 40 years this time.

I don't say that because I have any illusions about how the Taliban will rule. Based on their prior record in power, and on their behavior in the territory where they have regained control since America's retaliatory invasion in 2001, we can expect a thoroughly brutal regime, one that reduces women to the status of chattel and routinely deploys extrajudicial violence to eliminate all opposition.

But the United States has cordial relations with numerous brutal and oppressive regimes. Vietnam, for example, is still a one-party dictatorship with an abysmal human rights record, facts which have been no obstacle to the warming of relations. Saudi Arabia remains a linchpin ally in the Middle East despite being extremely repressive of basic rights (to the point of murdering an American-resident journalist), not to mention being responsible for a humanitarian catastrophe in Yemen that America fully abetted. We make alliances with those we think we need, not with those we like; America's 2001 invasion of Afghanistan required the cooperation of Uzbekistan's brutal then-dictator, Islam Karimov, and in recent years, the United States has explored openings with notorious human-rights violators like Myanmar (under President Obama) and North Korea (under President Trump) in an attempt to pry them out of the Chinese orbit.

The timetable of our willingness to reconcile with the Taliban, then, will not be driven by their progress on human rights, but by their potential usefulness to our aims. That, in turn, will depend on two factors: whether they succeed in unifying and ruling the country, and whether we share a common enemy.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

On the first front, it's far too soon to prognosticate. The extraordinary speed with which the Taliban have retaken the country as America pulled out makes it abundantly clear that there is no center of power in Afghanistan prepared to offer material resistance. That suggests the Taliban will also be able to consolidate their control with similar rapidity. Their first period in power put an end to bloody civil war and warlordism; for its second outing, it can claim the additional mantle of having defeated a foreign occupier. Those are not inconsiderable bases on which to claim political legitimacy. Now we have to see whether they have learned anything from their time in exile, and are prepared to govern effectively, however oppressively.

On the second front, it's all too easy to imagine who a common enemy might be:

Before our 20-year war, America's prior intervention in Afghanistan involved supporting the Pakistan-backed mujahideen resistance against the Soviet Union and its puppet government of the country. It would be completely in keeping with American foreign policy for us to try to run that script again against the People's Republic of China, our new geopolitical rival whose oppression of the Muslim Uyghurs has been reasonably characterized as a genocide.

The suggestion is somewhat tongue-in-cheek, but not entirely. The obstacles to such an idea are obvious: Afghanistan has a very narrow border with China, for example, and the Uyghurs are a Turkic people whereas the Pashto people who predominate among the Taliban speak a Persian-related language. But if the United States were seeking a safe haven from which to run weapons and men run by a group ideologically-disposed to support a jihad to liberate their co-religionists, Afghanistan has equally-obvious appeal. Remember, we're the country that laundered money for the Nicaraguan Contras through arms sales to Iran, a country we had no relations with and whose opponent, Iraq, we were providing covert militarily support to at the time — and then we turned around within a few years to invade Iraq in turn. We've engaged in less-likely gambits that working with the Taliban to harass the Chinese.

Re-running that script, though, would require the Taliban themselves to repeat the key error of their own last time in power, when they were seduced by lunatic dreams of glory retailed by Osama bin Laden. By attacking America, the leader of al Qaeda unquestionably changed the course of history, but he achieved none of his war aims. The "umma" has not been recreated; the House of Saud remains in control of Mecca with emphatic American support, as does the Israeli government in Jerusalem; and bin Laden's organization was operationally shattered years before his own assassination. From the perspective of the Taliban, meanwhile, their romance with global terrorism achieved nothing but to drive them from power for 20 years.

That gives some reason to hope that they've learned a lesson, and will not allow their territory to be a haven for such groups in the future. But if they have truly learned, they won't be seduced by American promises any more than they were by bin Laden's dreams.

Noah Millman is a screenwriter and filmmaker, a political columnist and a critic. From 2012 through 2017 he was a senior editor and featured blogger at The American Conservative. His work has also appeared in The New York Times Book Review, Politico, USA Today, The New Republic, The Weekly Standard, Foreign Policy, Modern Age, First Things, and the Jewish Review of Books, among other publications. Noah lives in Brooklyn with his wife and son.

-

Minnesota's legal system buckles under Trump's ICE surge

Minnesota's legal system buckles under Trump's ICE surgeIN THE SPOTLIGHT Mass arrests and chaotic administration have pushed Twin Cities courts to the brink as lawyers and judges alike struggle to keep pace with ICE’s activity

-

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire tax

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire taxTalking Points Californians worth more than $1.1 billion would pay a one-time 5% tax

-

‘The West needs people’

‘The West needs people’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

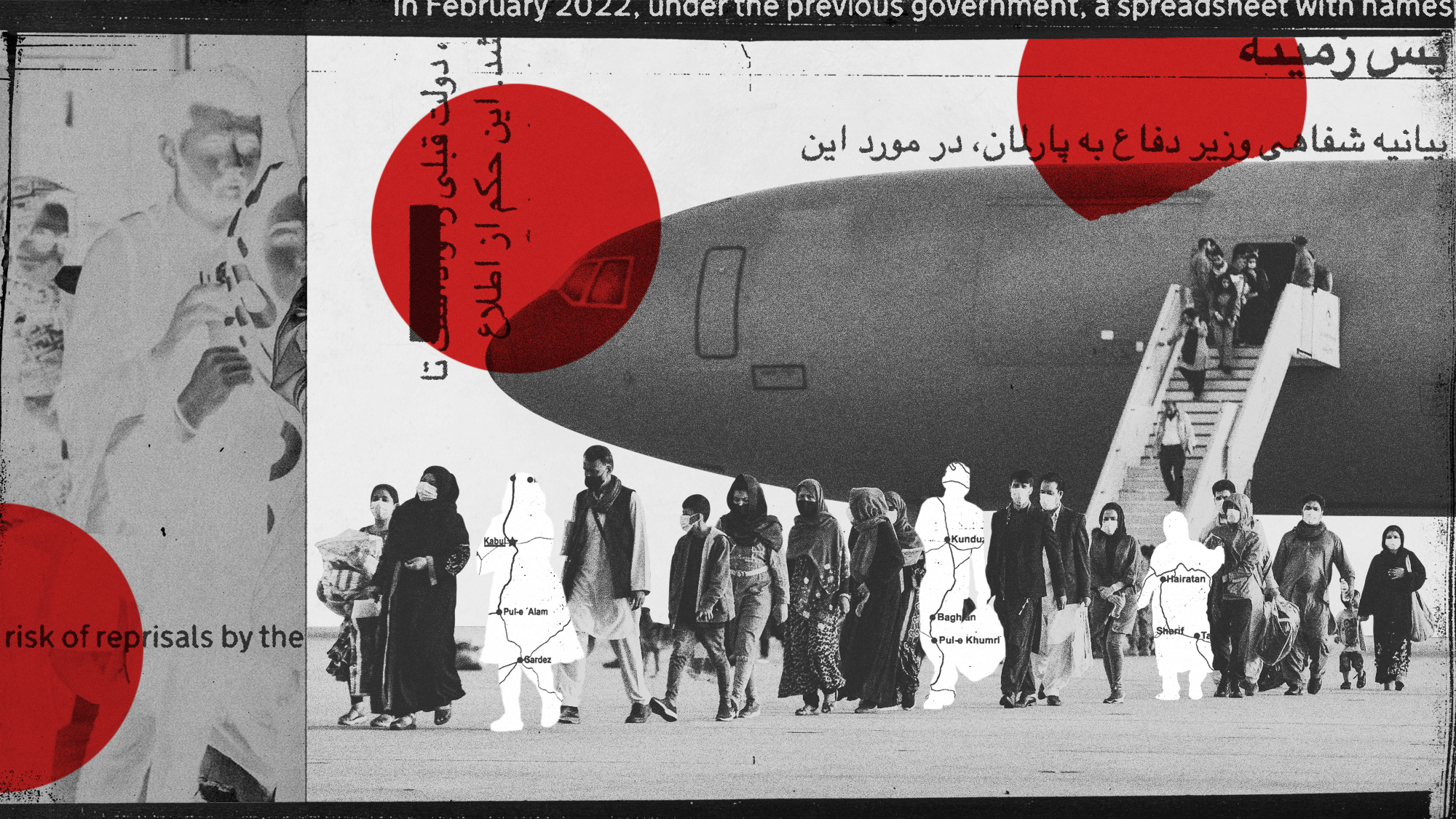

Operation Rubific: the government's secret Afghan relocation scheme

Operation Rubific: the government's secret Afghan relocation schemeThe Explainer Massive data leak a 'national embarrassment' that has ended up costing taxpayer billions

-

The Taliban’s ‘unprecedented’ crackdown on opium poppy crops in Afghanistan

The Taliban’s ‘unprecedented’ crackdown on opium poppy crops in Afghanistanfeature Cultivation in former poppy-growing heartland Helmand has been slashed from 120,000 hectares to less than 1,000

-

Ben Roberts-Smith: will more Afghanistan war crimes trials follow?

Ben Roberts-Smith: will more Afghanistan war crimes trials follow?Today's Big Question Former SAS soldier lost defamation case against Australian newspapers that accused him of murder

-

Can the UK rely on the British Army to defend itself?

Can the UK rely on the British Army to defend itself?Today's Big Question Armed forces in ‘dire state’ and no longer regarded as top-level fighting force, US general warns

-

Taliban releases 2 Americans held in Afghanistan

Taliban releases 2 Americans held in AfghanistanSpeed Read

-

American detained in Afghanistan for over 2 years released in prisoner exchange

American detained in Afghanistan for over 2 years released in prisoner exchangeSpeed Read

-

Afghanistan: A year after the withdrawal

Afghanistan: A year after the withdrawalopinion What did the U.S. leave behind when it pulled out of Afghanistan?

-

Prominent cleric who supported female education killed in Afghanistan bombing

Prominent cleric who supported female education killed in Afghanistan bombingSpeed Read