Why did the CIA resort to torture, anyway?

If these enhanced techniques worked, then why not use them on every detainee?

In prose that's both stomach-turning and succinct, the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence's majority Democratic staff has produced a prosecutorial record of the U.S. government's frantic, furtive, and flawed response to the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks.

By no means is it "neutral," as the Director of National Intelligence, James Clapper, told his employees today. "I don't believe that any other nation would go to the lengths the United States does to bare its soul, admit mistakes when they are made and learn from those mistakes," he added.

For the CIA, the examination is agonizing. Its ability to keep secrets, to keep commitments made to allies, to recruit sources, and even to recruit new intelligence officers rests on its reputation.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

After 9/11, Senate Intelligence Committee head Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) has acknowledged that everyone in a position of power had to be willing to leave their comfort zones and endorse policies that ran contrary to their assumptions about what was previously permissible. Feinstein, in fact, was not endorsing brutal interrogation techniques.

She was thinking about the National Security Agency's expanded surveillance powers, which, contrary to what the NSA's critics might claim, provided significant and unique intelligence that smothered a number of active plots against the United States and its allies in Europe. She was thinking about the somewhat arbitrary conventions that prevented the NSA from doing what it could do, and she was weighing the post-9-11 adjustment to security/liberty nexus that Congress had endorsed. She was also thinking about expanded presidential power to target confirmed enemies of the state with lethal action.

I have qualms about the targeted killing program, especially its rapid expansion after 2003. But I can see how policymakers could open their minds to include it in their arsenal of offensive weapons about terrorism. No question that the U.S. decided collectively that it had to violate or reinterpret international law in order to adjust to the reality of a global, possibly existential terrorist threat.

But torture?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

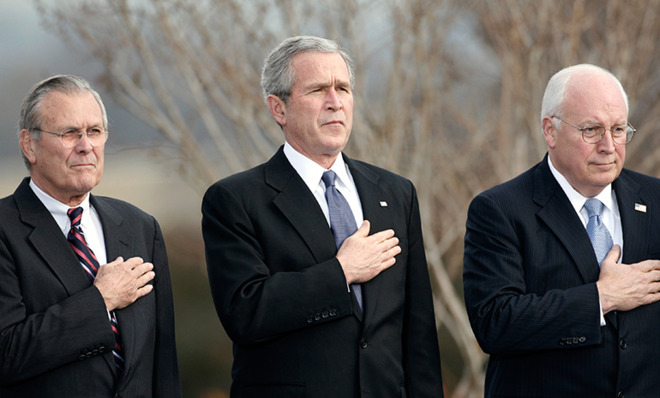

The quintessential defender of the CIA's torture program is former Vice President Dick Cheney. It's worth examining his justification.

He says that after 9/11, what he calls the alternative approach — sneeringly referred to by his friends as "relationship building" — wasn't working, and that there was hard intelligence that al Qaeda was about to explode a nuclear bomb inside the United States. (Mostly true.)

Step two of his logic: Everyone knew that intelligence pre-9/11 had failed and agreed that the U.S. had to be more aggressive in collecting intelligence. Still on board, here.

Step three: The U.S. had to track down as many people associated with al Qaeda and question them as quickly as possible. We're with you, Dick.

Step four: In order to get them to talk, in a hurry, we've got to torture the truth out of them. And that's where the wheels come off.

The paradiastole of "enhanced interrogation techniques" has always been the outlier. (Calling waterboarding, plainly torture, an "enhanced interrogation technique" is like calling a brothel "a place where people tend to have more sex.") Its justification was simply assumed. It had to work, because it was the logical, corporeal extension of a philosophy that says the state must co-opt and manage and sanction the use of violence for its own purposes, lest its mortal enemies sense and exploit weakness.

For Cheney, for the former CIA directors, and for the program supervisors, the projection of American power and resolve — and the willingness to hurt potential enemies if necessary — is the most effective, indeed, the most honorable way to secure the country. This is why it was easy for proponents of a war with Iraq to decide that containing Saddam Hussein was no longer sufficient, that he must be deterred from developing weapons of mass destruction, and that only force would accomplish it.

As the Senate report implicitly suggests, if these enhanced techniques worked, then why not use them on every detainee? If the intelligence gathered was so valuable, and so unique, why was the program so uneven, so arbitrarily applied, so inconsistently described, and so inherently controversial?

My guess is that it made no sense, even to those who ran it.

As the report makes clear, the use of the aggressive techniques were one part of the CIA's post 9/11 counter-terrorism program — perhaps its least useful part, but the part that headquarters and CIA managers seemed to obsess over. Perhaps it's because they knew it was inherently wrong and they were trying to adjust expectations to ensure that it seemed to produce enough intelligence to justify it. Other parts of the program worked well. The insistence on using torture undermined the rest of it, and may have fatally compromised the CIA's ability to respond quickly to the unexpected catastrophes of the future.

Marc Ambinder is TheWeek.com's editor-at-large. He is the author, with D.B. Grady, of The Command and Deep State: Inside the Government Secrecy Industry. Marc is also a contributing editor for The Atlantic and GQ. Formerly, he served as White House correspondent for National Journal, chief political consultant for CBS News, and politics editor at The Atlantic. Marc is a 2001 graduate of Harvard. He is married to Michael Park, a corporate strategy consultant, and lives in Los Angeles.

-

Metal-based compounds may be the future of antibiotics

Metal-based compounds may be the future of antibioticsUnder the radar Robots can help develop them

-

Europe’s apples are peppered with toxic pesticides

Europe’s apples are peppered with toxic pesticidesUnder the Radar Campaign groups say existing EU regulations don’t account for risk of ‘cocktail effect’

-

Political cartoons for February 1

Political cartoons for February 1Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include Tom Homan's offer, the Fox News filter, and more

-

How do you solve a problem like Facebook?

How do you solve a problem like Facebook?The Explainer The social media giant is under intense scrutiny. But can it be reined in?

-

Microsoft's big bid for Gen Z

Microsoft's big bid for Gen ZThe Explainer Why the software giant wants to buy TikTok

-

Apple is about to start making laptops a lot more like phones

Apple is about to start making laptops a lot more like phonesThe Explainer A whole new era in the world of Mac

-

Why are calendar apps so awful?

The Explainer Honestly it's a wonder we manage to schedule anything at all

-

Tesla's stock price has skyrocketed. Is there a catch?

Tesla's stock price has skyrocketed. Is there a catch?The Explainer The oddball story behind the electric car company's rapid turnaround

-

How robocalls became America's most prevalent crime

How robocalls became America's most prevalent crimeThe Explainer Today, half of all phone calls are automated scams. Here's everything you need to know.

-

Google's uncertain future

Google's uncertain futureThe Explainer As Larry Page and Sergey Brin officially step down, the company is at a crossroads

-

Can Apple make VR mainstream?

Can Apple make VR mainstream?The Explainer What to think of the company's foray into augmented reality