No, the U.S. doesn't have plans to nuke North Korea

Where did the idea for a "nuclear umbrella" come from, anyway?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

At this point, you've probably heard plenty about Leon Panetta's new book, Worthy Fights.

But it's not just in Beltway foreign-policy circles that Panetta's memoir of his time as President Obama's secretary of defense has caused a stir. The book is a hot-button issue in northeast Asia, too, with several South Korean newspapers claiming Panetta considered the use of nuclear weapons against North Korea in 2011. The JoongAng Daily, for example, headlined its article "Leon Panetta reveals nuke plan for South Korea." The Hankyoreh, a Seoul-based daily newspaper, titled its story "Leon Panetta's memoirs tells of willingness to use nukes in Korea."

Unsurprisingly, that's a bit of an exaggeration. What Panetta said is actually pretty boring. His book repeated the same, warmed-over talking points that any current or former secretary of defense might have when it comes to North Korea. The press reaction in Korea, however, illustrates why I think the standard Defense Department talking points are pretty dumb and why it is time to change the way Washington talks about nuclear weapons and U.S. security guarantees.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Here is what Panetta actually said:

If North Korea moved across the border, our war plans called for the senior American general on the peninsula to take command of all U.S. and South Korean forces and defend South Korea — including by the use of nuclear weapons, if necessary.

This is actually pretty mundane stuff. It's hardly any different from what Panetta said as secretary of defense, when he wrote an op-ed accompanying his visit in the South Korean newspaper Chosun Ilbo, pledging "to ensure a strong and effective nuclear umbrella over South Korea so that Pyongyang never misjudges our will and capability to respond decisively to nuclear aggression."

(More from Foreign Policy: What does China mean by 'rule of law'?)

It's hard to blame Panetta for using this kind of rhetoric. It is the party line, after all. But the problem is that such rhetoric places way too much emphasis on nuclear weapons in the U.S.-South Korea alliance, distracting from the really important stuff.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

We should forever ban the term "nuclear umbrella." Despite what the esteemed former secretary of defense said in his book and in op-eds, no such thing exists. There is no piece of paper where the United States commits to providing a "nuclear umbrella" to any country. The United States has a defense commitment to the Republic of Korea. Here it is:

Each Party recognizes that an armed attack in the Pacific area on either of the Parties ... would be dangerous to its own peace and safety and declares that it would act to meet the common danger in accordance with its constitutional processes.

There is no special commitment by the United States to respond to nuclear armed attack any differently than any other armed attack, nor is there a special commitment to use nuclear weapons "to meet the common danger." Nor should there be. A U.S. security guarantee is a big enough deal without any special nuke provisions.

Now, of course, the United States obviously has nuclear weapons that it could use if, as Panetta said, they were deemed necessary. But there is no "nuclear umbrella" separate from the security guarantee to act to meet the common danger posed by an armed attack.

Making this distinction is not nitpicking. Nuclear weapons represent only a fraction of the military capability that allows the United States to meet its security commitments. And while aggregate military capability matters, the most important factor is the overall strength of the political alliance between the United States and South Korea.

U.S. officials like to talk about the "nuclear umbrella" because they want to impart what you might call a "nuclear character" to U.S. security guarantees. Indeed, many of the stranger U.S. nuclear policies result from a quixotic effort to marry the existence of U.S. security guarantees to the existence of U.S. nuclear weapons.

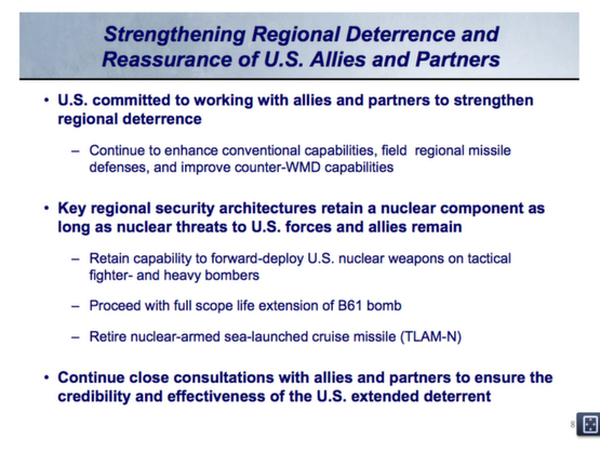

So, for an example of this awkward marriage, the United States used to forward-deploy thousands of tactical nuclear weapons in allied countries around the world, including South Korea. The United States had withdrawn most of these weapons by 1992, including all of the ones in South Korea. But even today, the United States retains a few hundred nuclear gravity bombs in certain NATO allies on the laughable premise that, in the midst of a conflict, the United States would hand these over to Belgian, Dutch, German, and Italian pilots. The 2010 Nuclear Posture Review emphasized the role of such weapons, arguing that nuclear character was imparted to U.S. alliances by the ability to forward-deploy nuclear-capable fighters and bombers. Here is a slide:

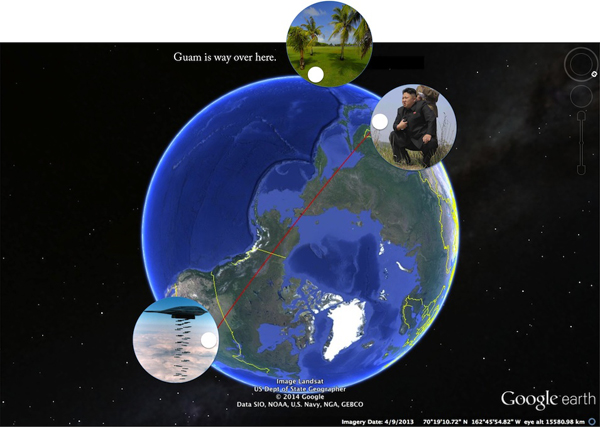

Although the slide doesn't say where the nuclear weapons would be forward-deployed, when it comes to reassuring South Korea, Defense Department officials will happily point toward Guam.

(More from Foreign Policy: Terrorists among us)

This nuclear posturing is stupid. I don't care what the Nuclear Posture Review implies; the United States would not nuke North Korea with weapons deployed in Guam. Here is a simple map showing several things:

1. Whiteman Air Force Base, where the United States deploys its B-2 bombers and their associated nuclear weapons.

2. North Korea, where Kim Jong Un lives.

3. A straight line between Whiteman AFB and North Korea.

4. Guam.

Yes, that's right. Guam is farther away from Missouri than North Korea. The Earth is round. Unsurprisingly, the United States practices direct flights from Missouri to northeast Asia, refueling over Alaska — because that's what it would actually do if it were ever to fly a nuclear-armed bomber to North Korea.

In fact, when a B-2 bomber made a surprise appearance during an exercise with South Korea, it arrived direct from Missouri. If we nuke Kim Jong Un, the bomb will have a 65305 postal code. The United States also flew B-2 bombing missions out of Whiteman against Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya. (The United States might, on the other hand, rebase conventionally armed bombers to Guam to increase the rate of sorties.)

I don't understand why the Department of Defense thinks it's a good idea to symbolize our security commitment with something that would be stupid to do. But I will point out that once we start inventing imaginary nuclear umbrellas that are distinct from our security guarantees, it's just a hop, skip, and a jump to asserting that our ability to do something really pointless shows how much we love our allies. At this point, we should just ask John Cusack to stand outside the Blue House with a boombox.

We don't need nuclear weapons to deal with North Korea in the first place. On the day an armada of bat-winged B-2s darkens the skies over Kim Jong Un's hermit kingdom, they will be carrying conventional weapons, not nukes. Were the United States to engage in a full-scale conflict with North Korea, we simply would not use nuclear weapons for the same reasons we did not use them in Iraq: We don't need nuclear weapons to defeat North Korea and there is no justification for victimizing the North Korean populace a second time. We can't argue that the leadership of the North Korean regime belongs in the dock at The Hague for violating human rights, then turn around put a hundred kilotons on Pyongyang like it's some Flying Buffalo card game. (Anyone have change for 10 million people?) Press reports indicate that the U.S. war plan for the Korean Peninsula is conventional-only, with a "counter-nuclear" option that exists to respond to a North Korean nuclear attack. That makes more sense than what Panetta implied.

Nuclear weapons don't deter the real threat from North Korea, anyway. The real problem with North Korea's nuclear capability is that it enables the conventional provocations North Korea carries out — like the sinking of the South Korean ship Cheonan that killed 46 South Korean sailors and the artillery attack against Yeonpyeong Island that killed another four people. Nuclear weapons simply don't deter these kind of low-level provocations by nuclear-armed states. Ask the Indians, for example, how well their nuclear weapons deter Pakistan's military operations in Kargilor the odd murderous rampage in Mumbai.

(More from Foreign Policy: The Swedish Navy is hunting a Russian submarine and doesn't have the tools for it)

U.S. officials shouldn't exaggerate the role of nuclear weapons. For one thing, they look silly. U.S. officials spent most of the 2000s arguing that the nuclear-armed Tomahawk cruise missiles, kept in storage since 1992, demonstrated Washington's commitment to extended deterrence for Japan and South Korea. Then in 2010, some of those same officials had to explain why they were retiring that system. As I have warned repeatedly, there is a very good chance that the United States Air Force will never make the F-35 nuclear-capable, which means the promises we made in the 2010 Nuclear Posture Reviewwill look silly.

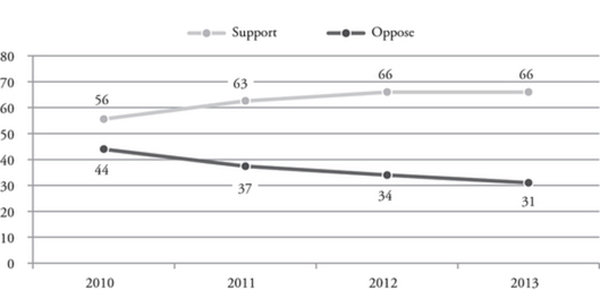

Most important, however, is that the United States should stop giving a false impression of the importance of nuclear weapons to South Korea's security. Here's a poll of how South Koreans feel about building a bomb of their own:

This poll is funded by the Asan Institute for Policy Studies. The Asan Institute is funded by Chung Mong Joon, the Hyundai scion who has run for president of South Korea and mayor of Seoul. Chung will probably make another bid for the presidency. Chung gave a speech at the Carnegie Endowment's nuclear policy conference in 2013 in which he called for South Korea to "temporarily withdraw" from the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT). Polls like this are subject to publication bias — since one might assume adverse results might not be published. I don't think 66 percent of the South Korean public actually wants a nuclear bomb, but there is definitely a small and vocal pro-nuke constituency. South Korea had a nuclear weapons program in the 1970s and 1980s that was probably suspended in the 1980s, though South Korea admitted to certain violations of its IAEA safeguards agreement as recently as 2000.

At the end of the day, I don't think South Korea will leave the NPT to build a nuclear weapon. (It is worth noting that South Korea admitted to certain activities voluntarily as part of a process of coming into compliance with its obligations.) Building the bomb is fundamentally not in South Korea's interest. If you want all the reasons that South Korea won't build a bomb, my friend Mark Hibbs articulated them beautifully in his own column for Foreign Policy last year.

You know who else should be articulating all the reasons that a South Korean bomb is a bad idea? The former secretary of defense. Panetta should be speaking candidly about the broader values that anchor the U.S.-South Korea alliance and about the conventional capabilities that actually provide for South Korea's defense. Above all, that means lightening up on all the "nuclear umbrella" talk, lest the South Koreans decide they want to hold the umbrella themselves.