The greatest threat to traditional churches isn't liberalism — it's the men who run them

In a hyperconnected era when it's hard to hide anything, the churches' scandals will out

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

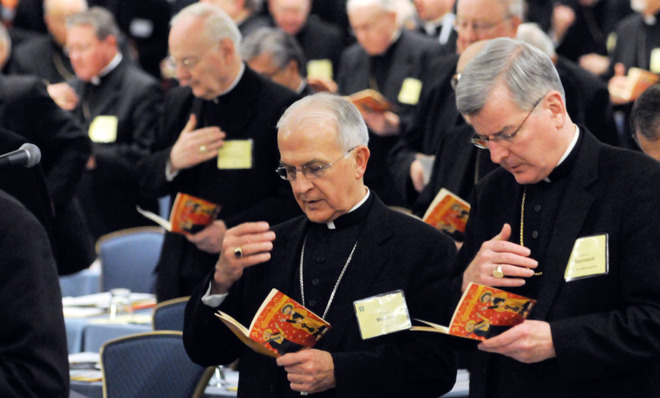

Have you heard the news about Archbishop John C. Nienstedt of St. Paul and Minneapolis? It seems he's been accused of making numerous sexual advances towards men while also leading his archdiocese's fight against same-sex marriage and regularly denouncing homosexuality in the most uncompromising terms possible. Nienstedt and his predecessor, Archbishop Harry Flynn, have also been credibly accused of covering up and showing indifference toward the sexual abuse of children by priests in the archdiocese.

I heard about both charges from blog posts by Rod Dreher, a conservative Christian friend, who learned of the first scandal from an article on the website of Commonweal, the liberal Catholic magazine, and was tipped off about the second one by a loyal reader who sent Dreher (in PDF form) the text of a sworn affidavit by Jennifer Haselberger, the former chief canon lawyer for the archdiocese, who gave her damning testimony in a civil lawsuit. The day after Dreher's post on the testimony appeared, The New York Times ran a substantial story about both scandals and the rising calls for Nienstedt's resignation.

So let's just say that if you hadn't heard the news before you started reading this column, you would have heard about it elsewhere before long.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

And that is a big problem for the churches, especially the conservative churches that seek to uphold and promulgate traditionalist views of morality and doctrine. Indeed, it's a far bigger and potentially more ruinous problem than the one posed by dogmatic liberals using government regulations to impinge on the freedom of certain believers to practice and live their faith.

Stated simply, the problem is this: Traditionalist churches preach a moral outlook that diverges sharply (especially in sexual matters) from the latitudinarian and egalitarian ethic of liberalism that increasingly dominates the lives of 21st-century Americans. When a scandal reveals that those who preach the stringent traditionalist view of morality fall far short of the standards they publicly demand of others, it makes them look like hypocrites and the church's teachings look like a cruel sham concocted by psychologically unbalanced clerics.

But that's not even the heart of the problem. To become a potentially church-destroying trend, which is what I think it could develop into over the coming decades, it must be mixed with one additional ingredient: The technologies of publicity (email, instant messaging, social media, news sites greedy for clicks) that have proliferated in the past generation.

Clerical hypocrisy and corruption are, after all, nothing new. They're as old as the church itself — because the church is run by human beings, and human beings find it extremely difficult to live up to what the church holds out as right behavior. The norm for much of the past 2,000 years has therefore been for ecclesiastical institutions — from the Vatican on down through denominationally unaligned Protestant parishes — to conceal their dirty laundry. When a priest, bishop, pope, or pastor was accused of impropriety, sexual or otherwise, the instinct was to cover it up, for the good of the institution.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

That instinct naturally prevailed within the institutions themselves, but it also permeated the culture of the laity. I saw this in action within the past decade or so when I worked as an editor at the conservative religious magazine First Things. To his credit, the magazine's editor-in-chief (a priest) wrote regularly and at length about the Catholic sex-abuse scandal, and he was also willing to publish essays (moderately) critical of Pope Pius XII, whose response to the Holocaust during World War II was being fiercely debated at the time.

But that didn't keep certain people within the First Thing orbit from objecting strongly to us running such articles. As a magazine produced (primarily) by and for faithful Christians, our role, we were told, was to publicly defend the church, not to add fuel to the fires lit and stoked by its enemies. We needed to circle the wagons and stop making such a public fuss about ugly facts that would only do damage to the institution.

Such arguments struck me at the time as expressions of a morally obscene craving for spiritual (and perhaps political) authoritarianism.

But let's leave that evaluation aside. What matters is that, regardless of whether faithful members of traditionalist churches should be working to conceal scandalous facts, today's technologies of publicity render such efforts effectively impossible.

Someone somewhere inevitably learns the scandalous truth and either publicizes the information directly or passes it along to someone who will. And the next thing you know, everyone's heard the foul and filthy news.

A nasty story now and then wouldn't do any lasting harm to the churches. But a seemingly endless string of scandals, especially when each new outrage seems to confirm a consistent pattern of hypocrisy, cruelty, and corruption among the men (always men) who run more traditionalist churches? That can do serious, even fatal damage.

Consider: Church attendance is already in decline. How long will the remaining parishioners keep returning to the pews when they're confronted by a persistent drip of scandal implicating people at all levels of the institution?

Then consider that liberalism's ethic of equality — including its embrace of same-sex marriage — seems in some ways to conform with, or at least plausibly follow from, the most subversive moral teachings of Jesus Christ. Why wouldn't a believer disillusioned by scandal just choose to be vaguely Christian — a "moralistic therapeutic deist," "spiritual but not religious" — while skipping the dogmatic and doctrinal trappings of institutional Christianity?

That is already a big part of our present. But it is going to be a much larger part of our future.

Many traditionalist Christians are terrified of precisely this prospect. But they tend to blame external influences, including a rising tide of secular liberalism (and sexual liberation) in the culture.

That's part of the story, but just a part.

Once we recognize the crucially important role of publicity in driving a mass exodus from the churches, something far more troubling becomes obvious — namely, that more than anything else it is the truth, and not some external cultural or political force, that may ultimately destroy the churches.

Not the indemonstrable "truth" that God doesn't exist. But rather the ultimately undeniable truth that, despite what they might say about themselves and what many of us would fervently like to believe about them, the churches are all too human. All the way down.

Correction: This article originally misstated the details of the allegations against Archbishop Nienstedt. It has since been revised. We regret the error.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.