The BMX boys of E.T.

The story of the stunt doubles behind one of Hollywood's most iconic scenes

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Robert Cardoza, Greg "Ceppie" Maes, and David Lee were five minutes late to a private screening of Steven Spielberg's E.T. at Culver Studios in California in 1982, months before the film would open to the public. It was the first time the three boys, hired as BMX stunt doubles for the movie, would get to see their work on a big screen. As they rushed up to the studio entrance, they came upon a locked gate and a woman holding a little girl's hands. The woman was kicking the gates with her heels and screaming, "Let us in, my daughter's in this movie!" The boys were convinced they had blown their chance to get in. It turned out to be Drew Barrymore's mom having a tantrum. Her outrage and insistent pleas eventually got them all in to the screening.

As the boys quickly settled into their seats, they eagerly anticipated the bicycle scenes. None of them had any idea what role their work would play in the overall movie.

At a crucial moment during the third act (the heart-wrenching scene in which the alien lay dying, just a few feet from his earthly friend Elliott) Cardoza heard a little girl's voice cry out just a few rows back, "Please don't let E.T. die. Please don't let E.T. die." Cardoza, 20 at the time, knew then that the movie he and his seven fellow BMX riders had worked on the previous summer for two weeks (the movie they knew by the working title A Boy's Life) would be a huge success. E.T. went on to become one of the highest-grossing films of all time.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

(More from Narratively: Master of the macabre)

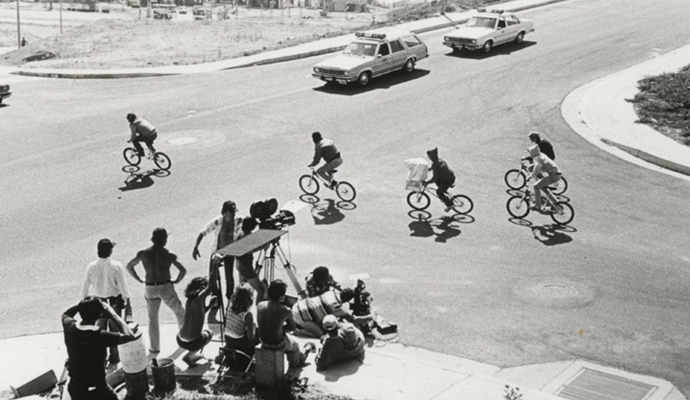

The moment that remains seared into the minds of audiences around the world is the pivotal chase scene near the end, when Elliott, with E.T. tucked in a basket on the front of his red bike and covered in a white sheet, is followed by his 16-year-old brother Michael and their three friends, Greg ("Can't he just beam up?"), Steve, and Tyler as they outwit and outrun government officials — all the grown-ups of the world, really — and fly away.

In the coming months, as adults and kids of all ages flocked to see the blockbuster, that chase sequence inspired thousands around the world to ride BMX bikes. Such bikes, or Bicycle Motocross bikes, are designed for dirt and motocross cycling. What sets them apart from "normal" bicycles is their ability to withstand the impact and rough terrain of a motocross track as well as the gyroscopes that allow their handlebars to spin freely. One of those thousands of BMX newcomers was Chris Hoy from Edinburgh, Scotland, who later went on to become one of the most successful Olympic cyclists of all time. "I was watching E.T. when I was six years of age," Hoy told The Telegraph in an interview when he retired from cycling earlier this year. "I'd never seen a BMX bike before and it was the scene at the end where they are getting chased by the police and they're all hammering through the streets in their BMX bikes. And I just thought, 'Wow, I'd like to give that a go.'"

* * *

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

As the movie was ending and applause filled the theater, the BMX stunt kids filled with pride, waited for their names to scroll up during the end credits. They never did. None of the eight BMX stunt riders were ever credited. Apart from a couple of articles in BMX magazines, the stunt kids whose work for the chase scene launched untold thousands of BMX riders were lost to history.

Also forgotten was the story of a bicycle broker from Torrance, California, and the relatively unknown Japanese BMX brand taken under his wing in 1979.

Present at the very same screening, at Culver Studios in West L.A., was Howie Cohen, in his forties at the time. Cohen was a savvy bicycle wholesale distributor and enthusiast who jumped at an opportunity when it presented itself. His company, Everything Bicycles, was the only hint at the story of the boys who never appeared in the credits.

"I remember tears of happiness flowing down my cheeks," Cohen reminisces. "The excitement of inclusion of BMX bicycles in this movie was way beyond my expectation or imagination."

(More from Narratively: The imaginarium of black cinema)

Born in 1939 in Minneapolis, Cohen rode his first tricycle when he was 18 months old and upgraded to a two-wheeler within a couple of years. His parents, Leo Sr. and RosaBelle Cohen, opened a bicycle shop the same year he was born and always encouraged their three kids — Louise, Howie, and Leo Jr. — to take part in local cycling events. The success of the shop took the family to California, where they opened three more. While working part time in the wholesale bicycle business, Cohen, at 18, began a lifetime passion of collecting bicycle memorabilia. He still owns fifty copies of the original E.T. poster.

Meanwhile, the Kuwahara Bicycle Company, a family business launched in Osaka, Japan, in 1918, was looking to expand to the United States. Kuwahara began by selling bicycle parts wholesale. The brand eventually began exporting bikes abroad and entered the American market in 1959. The bicycles they manufactured were for brands like Apollo, Schwinn, and Azuki, but they wanted to distribute a bicycle with the Kuwahara name on it.

On a fateful day in 1981, when Steve Adler, an MCA executive, stopped into Cohen's office to inquire about using Kuwahara bicycles for a movie, the exchange was an awkward one for Adler. Cohen recalls the conversation:

Cohen: "Great, how many do you want to buy?"

Adler: "We don't want to buy them. We want you to supply them to us."

Cohen: "Why? Why would I do that? Every time I go to the movies I buy a ticket, which is not very often, but whenever I go nobody gives me a free seat!"

Adler: "No, you don't understand, by co-operating you have the opportunity to an exclusive license to sell the licensed bicycles after the movie."

This piqued Cohen's interest.

Two weeks after the initial conversation with Steve Adler, Cohen loaded up his truck with the first batch of the 25 Kuwahara E.T. bikes and asked one of his employees, Robert Cardoza, to come along with him.

(More from Narratively: Master of a dying art)

Born in Torrance, California, Robert Cardoza rode his first bike when he was seven. "A bike to me was freedom. I realized early on that if I had a bike I could go anywhere," he remembers. "Anywhere. And at that time, Torrance didn't seem that big to me." Sometime in the late 70s, while riding his bike half a mile down from his house, Cardoza discovered Cohen's shop. The two became friends and Cardoza began hanging out there, soaking up as much as he could about the high-end bicycles Cohen carried, as well as working for him in shipping and receiving.

When Cohen took Cardoza along to the studio to deliver that first batch of bicycles, Cardoza didn't know what to expect. "I thought I was going to be the mechanic," he recalls. It was the first time the filmmakers and the actors would "meet" the bicycles. All the bikes needed to be adjusted specifically for each young actor and this job fell to Cardoza. "We just needed to adjust seat angle, seat height, and handlebar angle," said Cohen. "Everyone was happy." Spielberg himself even gave one of the bikes a go.

Read the rest of this story at Narratively.

Narratively is an online magazine devoted to original, in-depth and untold stories. Each week, Narratively explores a different theme and publishes just one story a day. It was one of TIME's 50 Best Websites of 2013.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day