What happened to Ireland's national pride?

In the wake of the financial crisis, Ireland has all but ceded economic sovereignty to Berlin and Brussels

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Over the next 30 years, the world will mark a parade of grim centennials, reflecting the civilization-altering events of World War I, the Russian Revolution, the Great Depression, the Holocaust, and World War II. But in Ireland, the centennials that should be a source of national pride — the Rising and independence won — will be met with a jarring reality.

What was the tyranny that Ireland set to throw off in 1916? Some 19 years before the Rising, in a speech he gave on the occasion of Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee, Patrick Pearse summed it up:

During this glorious reign [of Queen Victoria] Ireland has seen 1,225,000 of her children die of famine, starved to death whilst the produce of her soil and their labour was eaten up by a vulture aristocracy, enforcing their rents by the bayonets of a hired assassin army in the pay of the "best of the English Queens"; the eviction of 3,668,000, a multitude greater than the entire population of Switzerland; and the reluctant emigration of 4,186,000 of our kindred, a greater host than the entire people of Greece. At the present moment 78 percent of our wage-earners receive less than £1 per week, our streets are thronged by starving crowds of the unemployed, cattle graze on our tenantless farms and around the ruins of our battered homesteads, our ports are crowded with departing emigrants, and our poorhouses are full of paupers. Such are the constituent elements out of which we are bade to construct a National Festival of rejoicing!

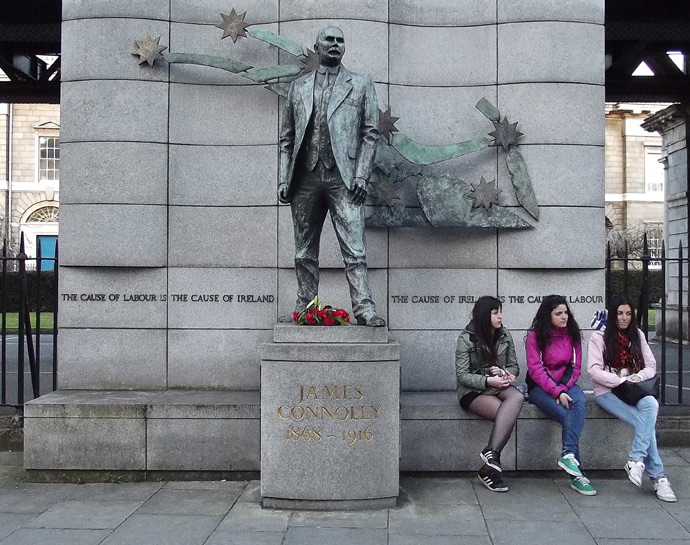

Those times produced men who hang over the Irish republic today like ghosts. Last summer, I saw graffiti in three cities quoting James Connolly, the greatest aphorist socialism ever produced and an important part of the Irish Revolution. He said of the British rule of Ireland: "The great appear great to us, only because we are on our knees: let us rise."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Above all, Connolly rose by falling. When the British executed Connolly on May 12, 1916, he had to be propped up in a chair, owing to wounds he had received in battle. Hailed a martyr in national song ever since.

What would he think of the Irish elections of 2016? And what would his comrades — like the strategist Michael Collins, or the militant and conservative nationalist Eamon De Valera — think? Pearse and his fellow rebels made stern doctrines into their political weapons: "We declare the right of the people of Ireland to the ownership of Ireland, and to the unfettered control of Irish destinies." An Irishman who said something like that today would be taken for a loon, an incipient fascist, an American-style Tea Partier.

As 2016 approaches, almost the entirety of Irish politics has revolved around one question: who deserves blame for how Ireland responded to the financial fiasco that erupted in 2008? The chief fact of the crisis is that Irish destinies were indeed fettered, that they were in the hands of German Chancellor Angela Merkel and the European Central Bank.

Of course, the fallout from the financial crisis has been nothing like Pearse's litany of horribles. The Irish may joke about "the Germans" who patrol Irish account ledgers, but there are no Black and Tans patrolling Irish homes and streets.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But the financial mismanagement has had an estimated cost of €7,000 per person in Ireland. Well into 2012, nearly 20 percent of Irish mortgages were in arrears (what Americans might call pre-foreclosure), jeopardizing one in five Irish homes with the country's unforgiving bankruptcy laws.

The worst disorder produced by this once rancorous nation? The man who threw an egg at a banker in 2009.

And the blows from the financial crisis still ache. The pain surfaced again after the release of Philippe Legrain's new book, European Spring, which describes how European central bankers pressured, even blackmailed, Ireland into a solution that ruled out giving any bondholders a haircut, then urged a bank guarantee that hung a €400 billion sword over the Irish taxpayer's head. As a result, everyone in Ireland knows someone who had to stop paying the mortgage, who cannot move because they are stuck in a home worth two-thirds of the note on it.

But even among the old Provisionals in surging Sinn Fein, the party that wants to throw off the U.K.'s association with Northern Ireland, none contemplate the idea that there might be a conflict between the euro zone and the sovereignty of the Irish people. The confreres of Gerry Adams hush all that and declaim their platform of being an "equal member" of the European Union, even if Germany and France are more equal than everyone else. Unlike France, the U.K., or Greece, there is not a single political force in Ireland that works to wrest "the unfettered control of Irish destinies" from Brussels.

Even after the financial fiasco, Ireland is a much wealthier country than it was a century ago. But there's something that makes me cringe for its soul. The Irish Times has an editorial explaining some of the recent benefits instituted among members of the European Union: lower roaming charges on mobile phone calls. Now Irish phone users won't be surprised by €50 overages. All this benefit cost them was €1.6 billion a year servicing the €202.9 billion of debt the taxpayers assumed from banks.

Meanwhile, Germany tells Ireland that they cannot discuss debt relief until Irish taxes are to Germany's liking. The year 2016 will be a lovely reminder that the Irish now wish for lower mobile phone bills — not political control of Ireland.

Michael Brendan Dougherty is senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is the founder and editor of The Slurve, a newsletter about baseball. His work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, ESPN Magazine, Slate and The American Conservative.