Why Hillary Clinton should run for an Obama third term

Obama is seen as a drag on a potential Clinton ticket. But the unfinished business of the center-left is where the votes are.

Conventional wisdom has it that President Obama's middling poll numbers will be a drag on Hillary Clinton's presumed march toward the presidency. The idea is that Clinton will have to somehow detach herself from Obama's legacy, because, as Ross Douthat at The New York Times put it, "political skill builds majorities, but popular policy successes cement them — and that is what has consistently eluded Obama." Or as Damon Linker argued at The Week, "she can't offer more of the same, because no one wants that."

Yet when it comes to the kind of domestic policy platform we can expect from a Clinton candidacy, it may be anything but a shift away from Obama. Instead, it will look a lot like a third Obama term, focusing on areas that should still have enormous popular appeal come 2016.

Over his first six years in office, Obama has followed through on significant promises advancing a center-left agenda. A Clinton candidacy will aim to consolidate these gains and build upon them.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Consider the issue of K–12 education. The United States has fallen behind our global peers in primary education achievement metrics for two main reasons: Inadequate quality and insufficient time spent in school.

Obama tackled the first problem with his Race to the Top initiative. It encouraged states to adopt the Common Core standards, increasing curriculum rigor throughout the country. It expanded charter schools and teacher evaluation systems to inject innovation and accountability into more public school systems.

Clinton could pick up where Obama left off by addressing the second problem. The United States ranks 28th out of the 38 OECD countries in the number of 4-year-olds enrolled in early education. Only 69 percent of our children attend pre-kindergarten programs, compared with 95 percent in France, the Netherlands, Spain, and Mexico.

Clinton proposed a universal pre-K plan during her 2008 campaign. She would have provided grants to states to make voluntary pre-K universally available to all 4-year-olds, including free schooling for low-income children and English-language learners. On the heels of New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio's successful push for universal pre-K in New York, it's not hard to imagine Clinton running on a similar plan again.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Second, consider the interlocking issues of higher education, student debt, and inequality, all of which are immensely important to a millennial generation that has been scarred by the Great Recession and has mostly aligned itself with the center-left. Obama has made economic inequality a consistent theme of his second term, calling it "the defining challenge of our time."

When it comes to the financial strain weighing on young people, Obama has taken action against both skyrocketing tuition rates and burdensome student debt. He developed a federal rating system to grade colleges based on their affordability. He urged Congress to go further and tie the system to federal student aid.

For student borrowers already weighed down by debt, Obama has expanded capped repayment and loan forgiveness options. More borrowers can now limit their federal student loan payments to 10 percent of their income, with any remaining balance forgiven after 20 years of repayment.

Clinton could make college more affordable for more students by resurrecting a promising idea that she briefly endorsed in her 2008 campaign. The idea would create "baby bonds" — savings devices that the government would endow to every newborn. This would give "every baby born in America a $5,000 account that will grow over time, so when that young person turns 18, if they have finished high school, they will be able to access it to go to college," Clinton said at the time.

Republicans ridiculed the idea, and Clinton backpedaled just days later. But inequality and student indebtedness have gained new prominence in our national consciousness during the Obama presidency. An idea that promises to help students afford college, promote savings from a young age, and alleviate intergenerational poverty might be a lot harder to mock in 2016 than it was just eight years earlier.

Obama has also pushed for workplace protections for women. He signed the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act into law, making it easier for women to sue for pay discrimination, and consistently advocated equal pay for equal work.

Clinton could pick up the mantle of workplace fairness and run on better maternity leave policy — an issue she has spoken publicly and personally about. The United States stands alone among developed countries in failing to guarantee new mothers paid leave from work. Clinton could endorse a plan like the FAMILY Act, which would guarantee 12 weeks of annual family leave for workers to care for new children or for a family illness while receiving two thirds of their normal wages.

There are undoubtedly other areas where Clinton could build on Obama's groundwork. As president, she'd continue implementing and refining the Affordable Care Act. She'd push for immigration reform if that remains unachieved. Perhaps she would try for the much-needed gun safety measures that have eluded Obama despite the disturbing regularity of mass carnage.

All of this is helped by the fact that Republicans have precious few ideas of their own to address these problems.

For all the talk of Obama fatigue, the promise of a Clinton candidacy would largely be a continuation of the consensus policy vision of the center-left. One Democratic pragmatist would replace another. While we'll have to wait for the exact contours of a Clinton policy agenda, we can be confident that much of it will take up the unfinished business of Barack Obama.

Joel Dodge writes about politics, law, and domestic policy for The Week and at his blog. He is a member of the Boston University School of Law's class of 2014.

-

What Nick Fuentes and the Groypers want

What Nick Fuentes and the Groypers wantThe Explainer White supremacism has a new face in the US: a clean-cut 27-year-old with a vast social media following

-

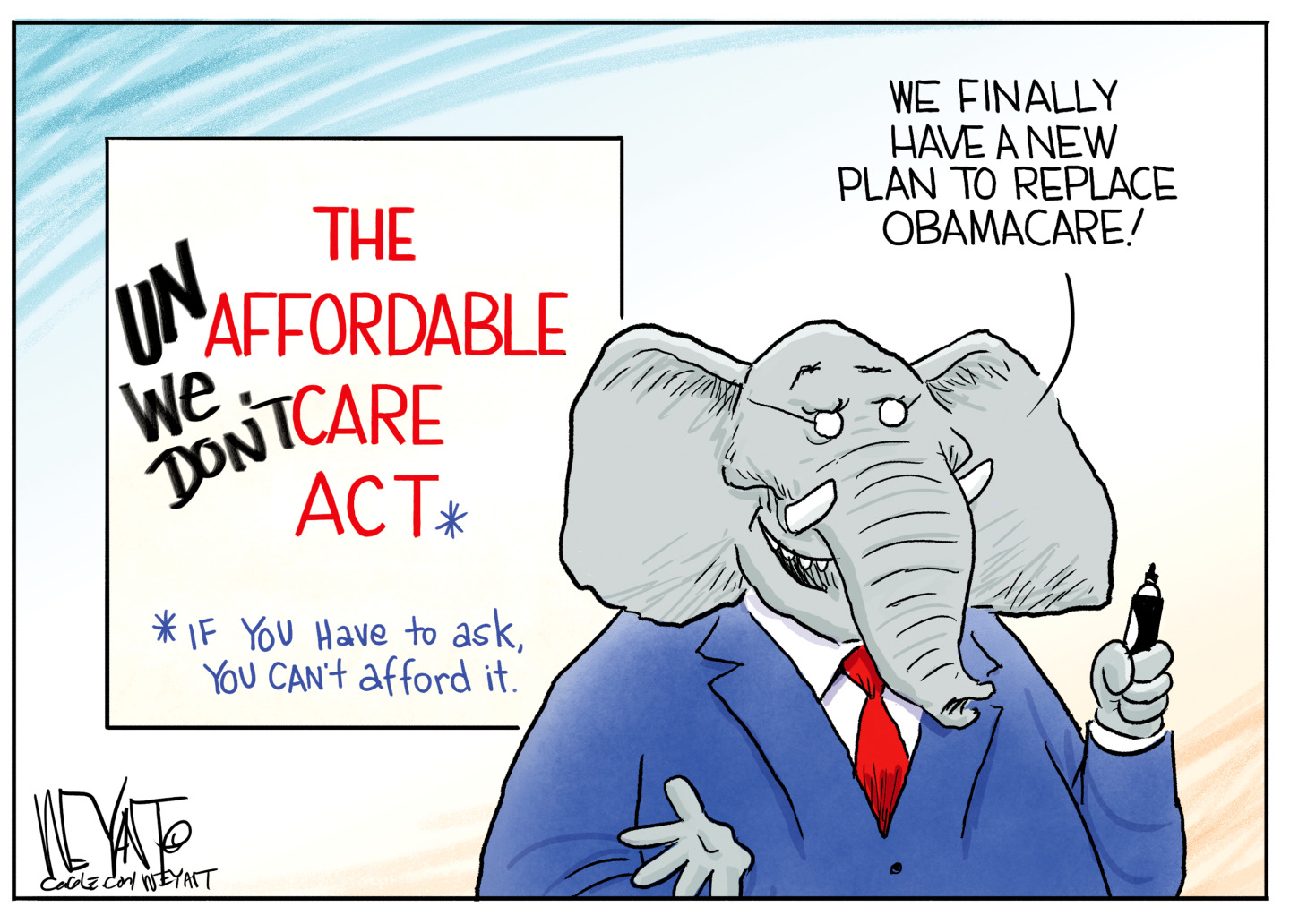

5 highly amusing cartoons about rising health insurance premiums

5 highly amusing cartoons about rising health insurance premiumsCartoon Artists take on the ACA, Christmas road hazards, and more

-

Codeword: December 21, 2025

Codeword: December 21, 2025The daily codeword puzzle from The Week

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are US billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are US billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration