The Isla Vista shootings are not about you. Or me.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Something about all of this is off.

Eliot Rodger's rampage through Isla Vista, California, reads as though it was cut out of a slasher film, and the moment his gunfire stopped echoing, those privileged enough to get paid to say or speak exploded with instant popular punditry.

So much of it is repetitive, derivative nonsense. But the nonsense was especially irritating to me. I'm one of those folks who gets paid to try and sort things out. I had nothing unique to write about the shooting, and so I chose not to. I wanted to wait, and read, and see. I'm not superior to those with instant opinions. I'd like to think I have more sense than some of them. And sensibility after an Isla Vista, I would propose, is an underrated virtue. (Derek Thompson, of The Atlantic, points out that is a unique failing of national figures to not know when they have nothing sensible to contribute to the public dialog.)

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

So, now to take a step outside of this post. I wrote that paragraph above, and when I read it back, I realized at once what was off.

It's so self-referential. It's about me.

It takes something horrible and cruel and random and makes it about me. I wrote it, and I believed it, because it made me feel better. It filled some need I had to feel something, a need that the tragedy had provoked. See? There goes the writer who has sense.

The pornographic allure of horrible crimes is one reason why Isla Vista rivets us. That's human nature. I'll take a pass on criticizing human nature. But human nurture; well, that's fair game.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Christopher Hitchens complained about the "national orgy of mawkishness" that followed the Virginia Tech School Shootings in April, 2007.

On Saturday night, I watched disgustedly as the president of the United States declined to give his speech to the White House Correspondents Dinner on the grounds that this was no time to be swapping jokes and satires. (What? No words of courage? No urging us to put on a brave face and go shopping or visit Disneyland?) Everyone in the room knew that this was a dismal cop-out, but then everyone in the room also knew that our own profession was co-responsible. If the president actually had performed his annual duty, there were people in the press corps who would have affected shock and accused him of "insensitivity." So, this was indeed a moment of unity — everyone united in mawkishness and sloppiness and false sentiment. From now on, any president who wants to duck the occasion need only employ a staffer on permanent weepy-watch. In any given week, there is sure to be some maimed orphan, or splattered home, or bus plunge, or bunch of pilgrims put to the sword. Best to be ready in advance to surrender all critical faculties and whip out the national hankie. [Slate]

It's kind of harsh, but it's also very true. False sentiment. Fact sloppiness. The surrendering of our critical faculties. Hitchens was discussing the elite reaction to tragedies, and I think his point, generally, is that the people who have discretion to decide, edit, arbitrate, and sort are constantly engaged in a war amongst themselves to defines tragedy downward, to turn it into low culture. Horrible, random, events that rivet our attention but do not pose existential threats to our lives are cheap carnivals of mindless maudlin. They are the new opiate of the masses, in some way.

So something inexplicable and macabre happens. We are understandably fascinated by it, and we want to know more. We personalize it by projecting our own experiences into the narrative. We interrupt the process of fact-gathering to make this about ourselves, because that's how we engage. Then we get angry or sad. Or, we wait until someone writes something, or Fox/MSNBC-bloviates something, that makes us angry, and then we use that bit of writing or bloviating to ventilate.

Here are three examples. John Hinderaker:

Beyond that, some might argue that Rodger was a prototypical liberal male, only carried to a pathological extreme. Consider the profile: socially awkward, convinced of his own brilliance but not notably successful in life, hungry for revenge against those who have done better despite their obvious inferiority, eager to gain power over others, but through political influence rather than firearms — is this not a typical liberal on Twitter, or elsewhere on the internet? Or, for that matter, in the Obama administration? Isn't state power the legal path to the long-awaited revenge of the liberal nerds? This strikes me as a plausible suggestion. [Powerline]

It's about Us. It's about exactly that thing I was telling you about before.

On the left, Michael Moore "no longer has anything to say" about such tragedies, except for the following, which apparently isn't anything

Everything I have to say about this, I said it 12 years ago: We are a people easily manipulated by fear which causes us to arm ourselves with a quarter BILLION guns in our homes that are often easily accessible to young people, burglars, the mentally ill and anyone who momentarily snaps. We are a nation founded in violence, grew our borders through violence, and allow men in power to use violence around the world to further our so-called American (corporate) "interests." The gun, not the eagle, is our true national symbol. While other countries have more violent pasts (Germany, Japan), more guns per capita in their homes (Canada [mostly hunting guns]), and the kids in most other countries watch the same violent movies and play the same violent video games that our kids play, no one even comes close to killing as many of its own citizens on a daily basis as we do — and yet we don't seem to want to ask ourselves this simple question: "Why us? What is it about US?" Nearly all of our mass shootings are by angry or disturbed white males. [Facebook]

It's about Michael Moore's long-standing views on gun control.

Now read this, from Joe The Plumber. That guy!

I am sorry you lost your child. I myself have a son and daughter and the one thing I never want to go through, is what you are going through now. But:

As harsh as this sounds — your dead kids don’t trump my Constitutional rights. [Barbwire]

It's about furthering Joe-the-freaking-Plumber's aspiration to be a political figure of importance, by which I mean someone who gets rewarded for spouting nonsense.

And then, predictably, it's about the OUTRAGE that people who have read Joe's blog post feel. And let's express that outrage by giving Joe exactly what we wants. Which is, of course, our published outrage.

Joe decided to write because someone who actually experienced the tragedy, the father of one of the dead kids, had the temerity to express his grief in public.

I would submit that in the hierarchy of those who deserve to be heard, family members of those involved rank higher than pundits, or avatars of a now defunct political movement, or those who want to start a new one.

But I would be out of sync, apparently, with the moment.

Marc Ambinder is TheWeek.com's editor-at-large. He is the author, with D.B. Grady, of The Command and Deep State: Inside the Government Secrecy Industry. Marc is also a contributing editor for The Atlantic and GQ. Formerly, he served as White House correspondent for National Journal, chief political consultant for CBS News, and politics editor at The Atlantic. Marc is a 2001 graduate of Harvard. He is married to Michael Park, a corporate strategy consultant, and lives in Los Angeles.

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

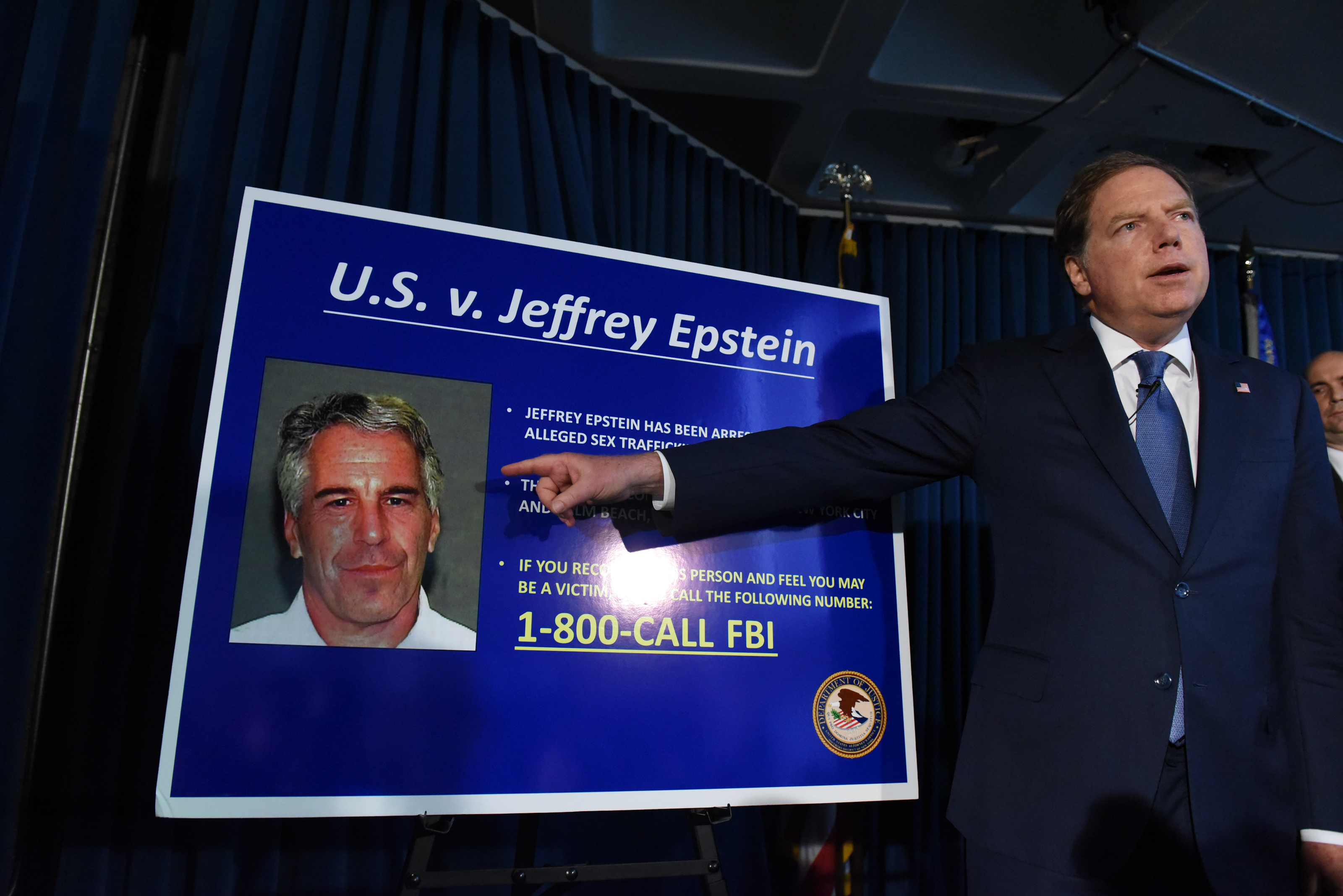

7 lingering questions about Jeffrey Epstein's death

7 lingering questions about Jeffrey Epstein's deathThe Explainer Truth can be as strange as conspiracy theories

-

3 things everyone is getting wrong about the El Paso-Dayton shootings

3 things everyone is getting wrong about the El Paso-Dayton shootingsThe Explainer Mental illness is a red herring — but so is Trump

-

Is it dangerous to lionize the heroes of school shootings?

Is it dangerous to lionize the heroes of school shootings?The Explainer Honoring the children who die saving classmates is laudable — but we should tread carefully

-

The fear we all live with

The fear we all live withThe Explainer What mass shootings have done to the American psyche

-

The sick phenomenon of school shooting contagion

The sick phenomenon of school shooting contagionThe Explainer Mass shootings can spread like a disease, with each massacre inspiring new rampages. Can the cycle of violence be stopped?

-

Why the Parkland conspiracy theories are different

Why the Parkland conspiracy theories are differentThe Explainer They aren't an attempt to make crazy sense of a senseless tragedy. They are a way of saying to the tragedy's victims and survivors: You aren't even worth arguing with.

-

Sex, drugs, and the Summer of Love

Sex, drugs, and the Summer of LoveThe Explainer Fifty years ago this summer, 75,000 young people flocked to San Francisco to "turn on, tune in, drop out"

-

What we know about gun violence may surprise you

What we know about gun violence may surprise youThe Explainer Contradictions abound