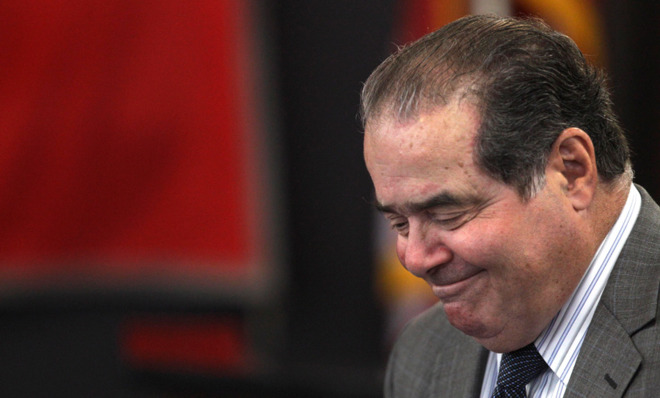

Why Antonin Scalia was right to defend a drug dealer

The conservative justice's exquisite defense of the Fourth Amendment is a credit to the American justice system

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Prado Navarette in August 2008 was driving 30 pounds of marijuana through California when he was stopped by the cops on suspicion of drunk driving. His case went all the way to the Supreme Court. And today, in a blistering dissent joined by three of the court's liberal justices — Sonia Sotomayor, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and Elena Kagan — Justice Antonin Scalia defended Navarette, arguing that the search of his car was a violation of the Fourth Amendment's protections against unreasonable searches and seizures.

But Scalia was unable to convince his conservative confreres, who joined a majority opinion by Justice Clarence Thomas that deemed the search legal. The issue before the court was this: Whether the Fourth Amendment requires an officer who receives an anonymous tip regarding a drunken or reckless driver to corroborate dangerous driving before stopping the vehicle.

Prado Navarette fell under suspicion after a 911 caller said Navarette had run her off the road. She described Navarette's truck and even told authorities the license plate number. Police took this as suspicion of driving under the influence of alcohol, and found the truck Navarette was driving. The cops followed him for five minutes before pulling him over, at which point they discovered he was not drunk. But his car was searched anyway, and the drugs were found.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Thomas says the cops were within their rights to rely solely on the anonymous witness' observations. Scalia's dissent rips the majority opinion limb from limb.

Scalia contends that police had no reason to credit the 911 caller's story in the first place, much less believe Navarette's erratic driving was the result of mental impairment. People may make a sudden or reckless-seeming maneuver in their vehicle for all sorts of non-criminal reasons. "I fail to see how reasonable suspicion of a discrete instance of irregular or hazardous driving generates a reasonable suspicion of ongoing intoxicated driving," Scalia writes (emphasis original). Amusingly, Scalia says that this one instance of dangerous driving could have been caused by Navarette's trying to avoid a pothole, or simply being distracted by an argument about sports with his brother.

Scalia contends that Fourth Amendment jurisprudence holds that officers must suspect an ongoing crime to stop someone. But in this case, "in order to stop the petitioners the officers here not only had to assume without basis the accuracy of the anonymous accusation but also had to posit an unlikely reason (drunkenness) for the accused behavior."

He admits that the anonymous call may have been a reason to observe the car for erratic behavior, but once the cops had observed Navarette's impeccable driving for five minutes, they no longer had any reason to believe Navarette was committing a crime. In fact, this observation should have discredited any suspicion. Further, he says the majority erred by asserting that Navarette could have somehow improved his drunk-driving once he became aware of the police. He writes:

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

I take it as a fundamental premise of our intoxicated-driving laws that a driver soused enough to swerve once can be expected to swerve again — and soon. If he does not, and if the only evidence of his first episode of irregular driving is a mere inference from an uncorroborated, vague, and nameless tip, then the Fourth Amendment requires that he be left alone. [SupremeCourt.gov]

Scalia concludes:

After today's [majority] opinion all of us on the road, and not just drug dealers, are at risk of having our freedom of movement curtailed on suspicion of drunkenness, based upon a phone tip, true or false, of a single instance of careless driving. [SupremeCourt.gov]

Both opinions are worth reading. I agree with Scalia that it is troubling that the court ruled today that a simple, uncorroborated phone tip can lead to a search of a person and their effects. At first blush that would seem to encourage malicious tipping. Scalia calls the majority's reasoning "a freedom-destroying cocktail."

Having said all that, while I think Scalia easily has the better of the argument in Navarette v. California, it is worth reflecting on what a credit this case is to our judicial system. In most countries on Earth, the top jurists in the nation would never question whether a single search initiated by local police was reasonable and legal, especially when it resulted in the apprehension of a man who was committing an arguably graver offense than the one of which he was suspected. Indeed, this is unusual by the standards of the rest of the world and history, and a great inheritance from the common-law tradition.

Now if only the court would adopt Scalia's high standard for other cases, including the search of persons on city streets and the collection of data by the national security apparatus.

Michael Brendan Dougherty is senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is the founder and editor of The Slurve, a newsletter about baseball. His work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, ESPN Magazine, Slate and The American Conservative.

-

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?Podcast Plus, what does the growing popularity of prediction markets mean for the future? And why are UK film and TV workers struggling?

-

Properties of the week: pretty thatched cottages

Properties of the week: pretty thatched cottagesThe Week Recommends Featuring homes in West Sussex, Dorset and Suffolk

-

The week’s best photos

The week’s best photosIn Pictures An explosive meal, a carnival of joy, and more

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred